The Vaginal Microbiome: A Delicate Ecosystem

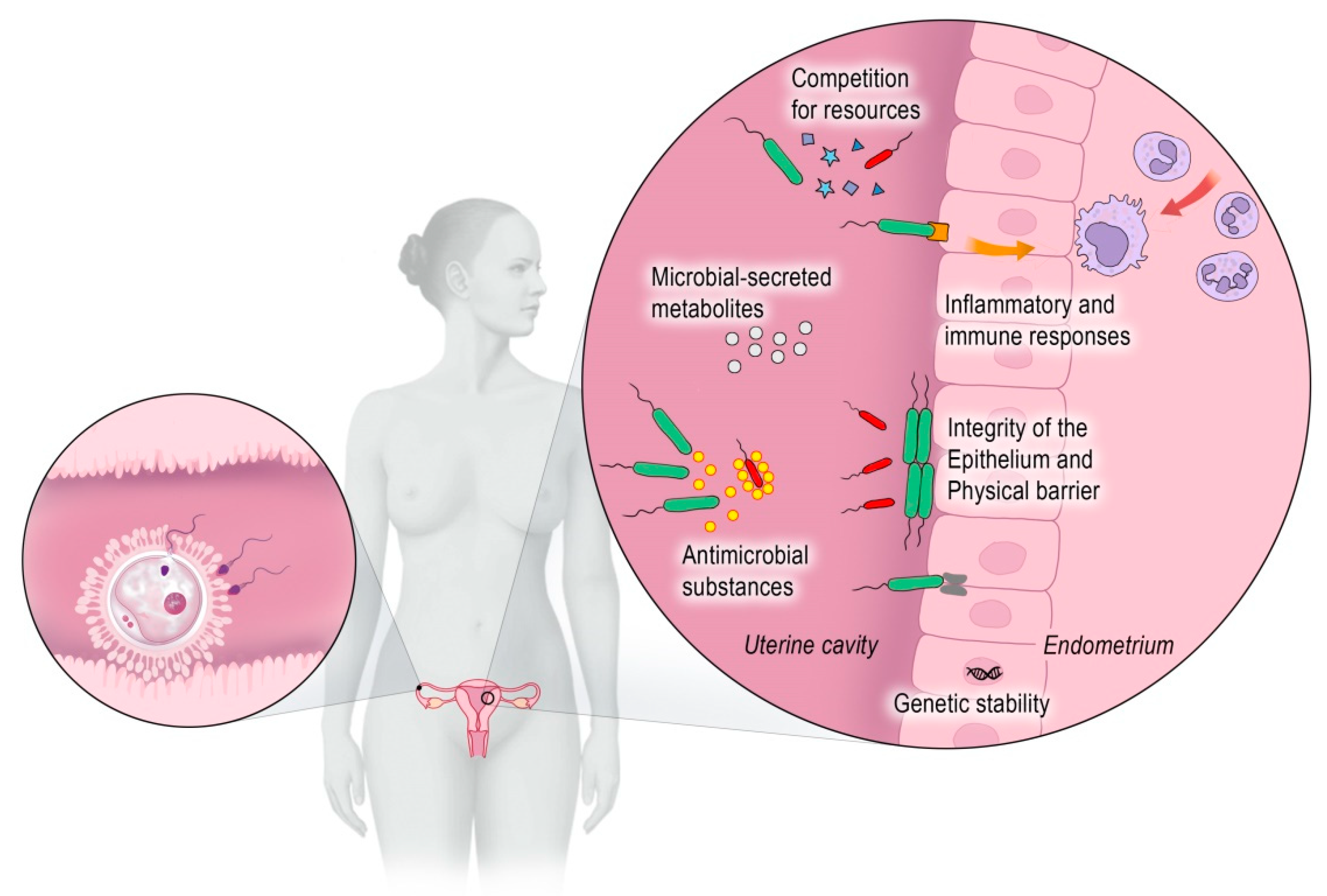

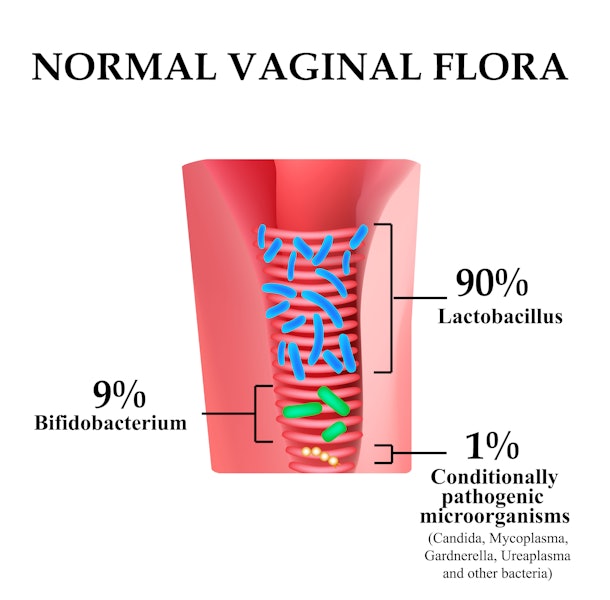

The vaginal microbiome consists primarily of Lactobacillus species, which play a protective role by maintaining a low pH and producing antimicrobial compounds. A healthy vaginal microbiome defends against infections such as bacterial vaginosis (BV) and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (Ma et al., 2012; Borges et al., 2014).

However, this ecosystem is sensitive to hormonal fluctuations, psychological stress, sexual activity, hygiene, and even relationship dynamics (Younes et al., 2018; MacIntyre et al., 2015). The question arises—how does the shift from physical intimacy to digital intimacy influence this microbial balance?

Image URL-https://sl.bing.net/blEmGXx3Dqu

Virtual Sex: A New Norm in Intimacy

Technologies like VR headsets, haptic feedback devices, and remote-controlled sex toys are blurring the lines between physical and digital pleasure. These innovations gained traction especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, as social distancing prompted people to seek alternative means of intimacy (Markus et al., 2019).

Though they eliminate physical microbial exchange, virtual sexual behaviours still influence the psychoendocrine system—which is directly linked to vaginal immunity and microbiota stability (Cortes et al., 2020; Gilbert et al., 2018).

Image URL- https://sl.bing.net/jw1u82S7TDE

Psychological Stress and the Microbiome

One of the key regulators of vaginal health is psychological stress. High stress levels increase cortisol, which in turn disrupts the balance of estrogen, a hormone essential for maintaining vaginal epithelial integrity and Lactobacillus dominance (Kaul et al., 2020).

While virtual sex can reduce performance anxiety and provide safer spaces for exploration, it may also lack the emotional depth and oxytocin release associated with real-life intimacy. For some users, this can lead to increased feelings of loneliness or dissatisfaction, inadvertently contributing to vaginal dysbiosis through chronic stress (Younes et al., 2018).

Hormonal Responses to Digital Intimacy

Physical sexual activity stimulates oxytocin, dopamine, and estrogen, promoting vaginal lubrication, tissue regeneration, and immune function (Koren et al., 2012). Although immersive virtual sex can mimic the psychological aspects of arousal, studies have yet to determine whether hormonal release is comparable. The absence of adequate estrogenic response could result in a rise in vaginal pH, decreased mucus protection, and vulnerability to infections such as BV and candidiasis (Ravel et al., 2011; Fettweis et al., 2014).

Behavioral Changes: Less Sex, Less Microbial Diversity?

Interestingly, regular physical intimacy introduces microbial diversity and stimulates vaginal immune regulation, which some studies suggest may help build resistance to pathogens (Zhou et al., 2020). A shift toward virtual-only experiences may reduce such exposures, creating a more sterile vaginal environment that may not be optimal in the long term and then lack of exposure to semen, skin flora, and non-pathogenic bacteria may reduce the microbiome’s adaptive response, further reinforcing the need to explore how these tech-driven habits affect vaginal microbial evolution (Lewis et al., 2017; Ceccarani et al., 2019).

Implications for Bacterial Vaginosis and STI Risk

One might assume that avoiding physical contact would reduce risks of bacterial vaginosis or STIs. While this is true for transmission, BV is not solely sexually transmitted—it is also caused by internal imbalances in microbial communities.

If virtual sex leads to less hormonal regulation, higher stress, or altered hygiene practices (e.g., prolonged device use), it may still increase BV risk even without traditional intercourse (Bradshaw et al., 2006; Campisciano et al., 2020).

Image URL-https://sl.bing.net/d25SqxHJugK

The Research Gap

Despite these connections, there is currently no peer-reviewed study directly linking virtual sexual behavior to changes in the vaginal microbiome. This represents a major gap in women's digital health research. Given the growing popularity of virtual intimacy platforms, researchers must examine how emerging sexual technologies intersect with microbiology, psychology, and hormone science.

Conclusion

As virtual intimacy becomes more integrated into human behavior, we must broaden our understanding of its biological consequences. While the technology promises safer and more accessible sexual experiences, it is crucial to assess its long-term impact on vaginal health. The future of female sexual wellness must include the microbiome as a critical health marker, particularly as we redefine intimacy in the digital age.

References

- Ma, B., Forney, L. J., & Ravel, J. (2012). Annual Review of Microbiology, 66, 371–389.

- Borges, S., Silva, J., & Teixeira, P. (2014). Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 289(3), 479–489.

- Markus, A. R., et al. (2019). Sexuality & Culture, 23(4), 1173–1192.

- Younes, J. A., et al. (2018). Frontiers in Microbiology, 9, 452.

- Kaul, R., et al. (2020). Fertility and Sterility, 113(5), 931–939.

- Gilbert, J. A., et al. (2018). Nature Medicine, 24(4), 392–400.

- Koren, O., et al. (2012). Cell, 150(3), 470–480.

- Ravel, J., et al. (2011). PNAS, 108(Suppl 1), 4680–4687.

- Fettweis, J. M., et al. (2014). Nature Medicine, 25(6), 1012–1021.

- Bradshaw, C. S., et al. (2006). Journal of Infectious Diseases, 193(11), 1478–1486.

- Lewis, F. M. T., et al. (2017). Microbiome, 5, 81.

- Ceccarani, C., et al. (2019). Scientific Reports, 9, 14095.

- Zhou, X., et al. (2020). PLOS ONE, 15(2), e0227784.

- Campisciano, G., et al. (2020). Scientific Reports, 10, 1103.