This is part II of a two-part article. Part I can be found here.

Champion

Today the Company is thriving, and I am the president and CEO of Astex UK.

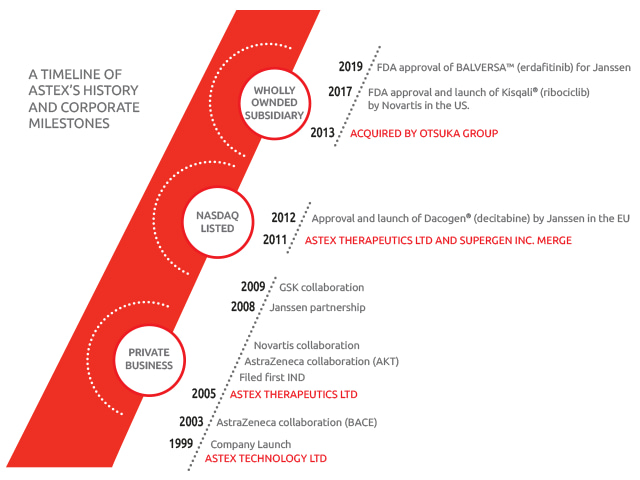

In April 2019, we celebrated Janssen receiving accelerated marketing authorisation in the USA for a first-in-class selective FGFR inhibitor, Balversa (erdafitinib), which resulted from our collaboration with them. Balversa has been approved for the treatment of adults with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma, and who have susceptible fibroblast growth factor receptor FGFR3 or FGFR2 genetic alterations. Balversa is an excellent example of precision medicine as the companion diagnostic was approved alongside it.

The approval of Balversa followed on from the FDA approval, in 2017, of Kisqali (ribociclib), a selective cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor that resulted from our collaboration with Novartis. Kisqali was approved as a first-line treatment for advanced breast cancer in combination with an aromatase inhibitor and data from its use in patients continues to widen its potential.

The involvement of Astex in the approval of two breakthrough medicines makes me immensely proud and is testament to the strength and hard work of the entire team. However, not all of our pharma partnerships have resulted in success; our Alzheimer’s collaboration with AstraZeneca on BACE ended in litigation!

Today we also have an extensive internal pipeline of programs in earlier stages of discovery and development for the treatment of a variety of cancers and diseases of the central nervous system. I have high hopes for similar successes. Furthermore, we are highly active in the Open Innovation ecosystem, with multiple collaborations with a range of world-class academic centres.

As Astex has grown I’ve gained some useful insights. I share with you below some of these that may be helpful as you embark on journeys of your own.

Adapting to a changing environment

During my career at Astex I’ve been fortunate to experience a number of different roles, which has meant that I have had to adapt and evolve every step of the way. I started out as a scientist and as chief scientific officer (CSO), steeped in the world of research and development. In November 2007, I was appointed as CEO, which required a very different skill set. It is recognised that the scientific founders of a company do not always make the best commercial leaders. Transitioning from CSO to CEO requires the ability to adapt and evolve and the conviction to make difficult decisions where needed to ensure the success of the business. Although I am a scientist by training, my time at GlaxoWellcome helped me appreciate commercial perspectives and I think that these insights and experiences were critical to my success as a CEO. Back in 1999 when we started Astex, it was much rarer for UK biotech company execs to have significant big pharma experience. My time at GlaxoWellcome meant I understood first-hand the big pharma mindset and this perspective was especially helpful when we later negotiated the partnerships.

Of course, there are a number of things that you can do to set yourself up for future success before you embark on the journey.

Setting up for success

When building a successful business, it is important to nurture a constructive and productive culture. Astex’s culture is all about encouraging scientific rigor and debate. It is not about people or personalities, as can sometimes be the case, it is simply about good science. Once you develop a reputation for high-quality science then it becomes easier to establish good pharma and academic partnerships, which is key for a small biotech. This is why I always encouraged Astex scientists to publish in high profile scientific journals. I feel passionately that this has been one of the principle reasons for Astex’s success today.

Another important factor to is to acknowledge the need for good advice. No one can know everything, so ensure you proactively build relationships with people who can help mentor you on the journey, share their own experiences and provide some useful feedback. Tim Haines, the first CEO of Astex, was a key mentor to me. He gave me space to build our technology platform but also helped me see the commercial perspective of the business. In the early years the Astex Board was chaired by Stephen Bunting, from Abingworth, and then Peter Fellner, both highly experienced and widely respected in the life sciences industry and both of whom provided careful guidance and advice to me after I had become CEO.

Cultural insights and transitions

Astex’s three phases of growth and development have involved three very different and diverse cultures from the UK, US and Japan. It hasn’t always been easy to navigate these, but my background as a British Asian has meant that I have an acute appreciation of different cultures, and that has definitely helped.

When Astex merged with SuperGen in 2011, we became a US company with a site in California and new US colleagues. Americans have an infectious enthusiasm for everything. It is a wonderful gift to see the world so positively and to have a can-do attitude. Us Brits admire this hugely but are much more reserved, which can sometimes limit our influence. Americans also have a much greater appetite for risk and are much more comfortable with failure. Part of this is of course to do with scale. The US has huge resources which must provide a strong foundation and feeling of security.

Being acquired by Otsuka gave me a new appreciation for Japanese culture. I think it is fair to say that there are more similarities between UK and Japanese culture than there are between US and Japanese. Both the UK and Japan are islands and have a long history. When we were approached by Otsuka I was intrigued as my initial discussions with the company president were all focussed on building personal connection, trust and rapport, with little focus on our R&D activities. I understand now that this was a positive sign, that Otsuka was building trust, evaluating my intentions and taking a long-term view. I also now appreciate that ambiguity is at the heart of Japanese culture and that it is important to progress a number of options for as long as possible to reduce risk before a final decision is made. This approach can sometimes seem frustrating to westerners, but given my Asian background I seem to find it less challenging.

Funding the Journey

In the first four years, Astex raised around £50m in three venture capital rounds, which was at that time one of the largest VC funding amounts for a European biotech company. In addition, the company was able to secure another £80m in research funding and upfront payments from pharma companies with whom we had partnered several of our programs. Despite this financial backing, fundraising was an almost perpetual activity in our initial phase of growth, and several times we were very close to running out of cash. This was due to the high R&D expenditure, especially as our compounds reached the clinic, and the eventual reluctance of VCs to provide further funding.

When we eventually became a public company there was a sense that we had ‘grown up’. After all, we now had to strictly adhere to all the good governance and confidentiality obligations that come with this. We were also being regularly scrutinised by biotech analysts and public investors. These audiences can be brutal, especially in the US, where they are both very direct and also very well informed. It is therefore important to be well prepared, robust and resilient. For Astex, becoming a US public company was not all pain, and indeed was a necessary step if we were to continue to grow. The US has the most established life sciences industry and a deep biotech-friendly financial market, which helps to create a robust, supportive environment for company growth.

Harren's top tips:

- Build options and be flexible

- Instill an entrepreneurial spirit and focus on rigorous science

- Continue to invest in your technology platform – it is key to innovation

- Choose your pharma partners carefully

Reflections: 20 years on

When I look back over the twenty years since co-founding Astex, several things come to mind. A lot has changed today for companies embarking on the same journey and there is lots of room for optimism. Today, companies are raising more than ever in their Series A rounds, and the so-called ‘valley of death’ (the time between a basic science discovery and the decision to commit resources to develop the idea into a drug) has, for some companies at least, become less of a major issue.

Some challenges still remain. There is still no significant critical mass of public listed biotech companies in the UK, and those that are public are largely choosing to list on NASDAQ rather than embrace our own public markets. However, success can be viewed in many different ways, and the UK continues to be Europe’s leading life sciences R&D powerhouse. Furthermore, the UK life sciences ecosystem has matured significantly in the last 15 years, with a strong interdependence between academia, biotech and big pharma. This environment should help nurture the next generation of biotechs whose ambition, as was the case for Astex, is to innovate, discover and develop new medicines for patients.

My final piece of advice for new companies would be to focus on high-quality science and build multiple options for commercial deals, the biotech sector evolves very fast, so you need to be prepared and nimble. Time is the most important asset.

Acknowledgement: The author would like to thank Sue Charles and Ashley Tapp for support and inspiration in the preparation of this article, and all employees and supporters of Astex past and present in making the journey possible.

About the author: Dr Harren Jhoti FRS co-founded Astex in 1999 and was Chief Scientific Officer until November 2007 when he was appointed Chief Executive Officer. Today he is President and CEO of Astex, UK.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Biotechnology

A monthly journal covering the science and business of biotechnology, with new concepts in technology/methodology of relevance to the biological, biomedical, agricultural and environmental sciences.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

... and part two even better as drugs reach patients! A true achievement - brilliant