From glacier to tap: Identifying local water resource vulnerability in Alberta, Canada

Published in Sustainability

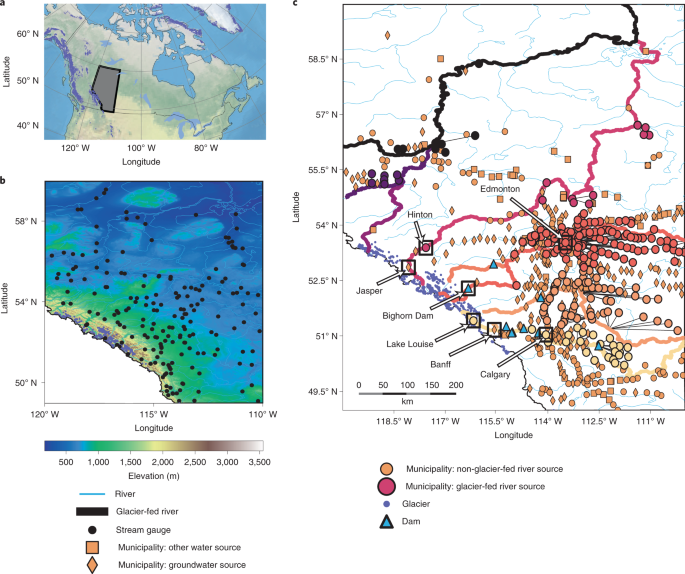

This project, described in more detail in the paper here, began when my PhD supervisor and co-author, Dr. Valentina Radic, recommended that I find Canadian streamflow data and see if I could find ways in which glacier-fed rivers behaved differently than non-glacier-fed rivers. It turned out that glacier-fed rivers in Alberta had a unique characteristics, and the strength of this ‘uniqueness’ depended non-linearly on the area fraction of ice in the watershed (percentage glacierization). This finding was exciting because we could calculate the percentage glacierization at any location along a river. In order to estimate how important glaciers were to communities in the province, we next needed to find out where along a river each community sourced their water from. I assumed that this would be a relatively straightforward step, but I quickly learned that this was not the case.

In the absence of a regional database, I started patching together the pieces that I could find. Some municipal websites would clearly state their water source; others were more opaque, but might name the utility provider; some would have no information at all. Sometimes I would have to email or phone city hall or the utility providers directly; sometimes these exchanges were brief, while other times the response would be at the end of a chain of forwarded emails between local people who were searching for the same information that I was. I read local news articles and city council meeting minutes, where there were discussions about changes to local water infrastructure, or discussions about funding, or partnerships with neighbouring communities, or water restrictions during drought. Answering the water source question was a surprisingly fun puzzle to solve where I could build a connection between myself and the communities whose future I was interested in.

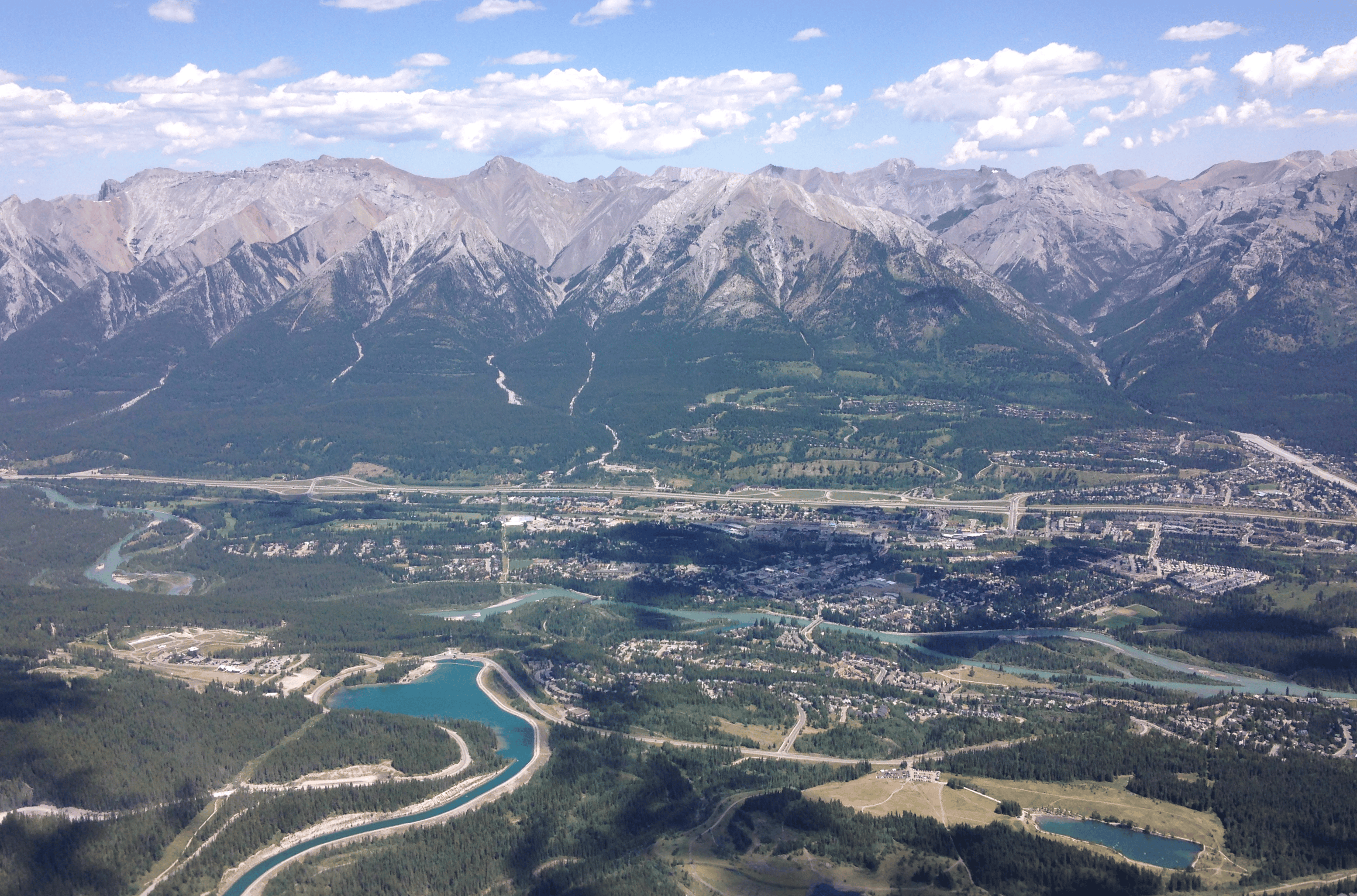

Solving this puzzle also led to some unexpected information. Travelling downstream from its glacial source, water in the Bow River flows through the smaller communities of Lake Louise, Banff, Canmore, and Cochrane before reaching the most populated city in the province, Calgary. However, despite all being situated on the Bow River, these neighbouring communities have different sources: Lake Louise sources from the Bow River; Banff sources from groundwater wells; Canmore sources from both wells and from a reservoir (not fed by the Bow); and Cochrane again sources from the Bow. Interestingly, Calgary sources their water from both the Bow River, which is glacier-fed and supplies the north half of the city, and from the Elbow River, which is not glacier-fed and supplies the south half of the city. So, if the Bow River were to change substantially along this course, the potential arose that not only would it impact neighbouring communities differently, but it could also impact neighbouring neighbourhoods differently.

Through detailing these water source networks throughout the province, I learned that the relationship between people and rivers was more complicated than I had expected. I’m left wondering: how complex are the water sources for communities in other glaciated regions? And how much does this matter for people as the ice retreats?

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Climate Change

A monthly journal dedicated to publishing the most significant and cutting-edge research on the nature, underlying causes or impacts of global climate change and its implications for the economy, policy and the world at large.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Hi, good work Sam. I'm also working on the dynamics of tidewater glaciers in Svalbard.