How Chlamydia tames the killer: mode of host-immune evasion revealed

Published in Microbiology

The paper in Nature Microbiology is here: https://go.nature.com/2tvEXLq

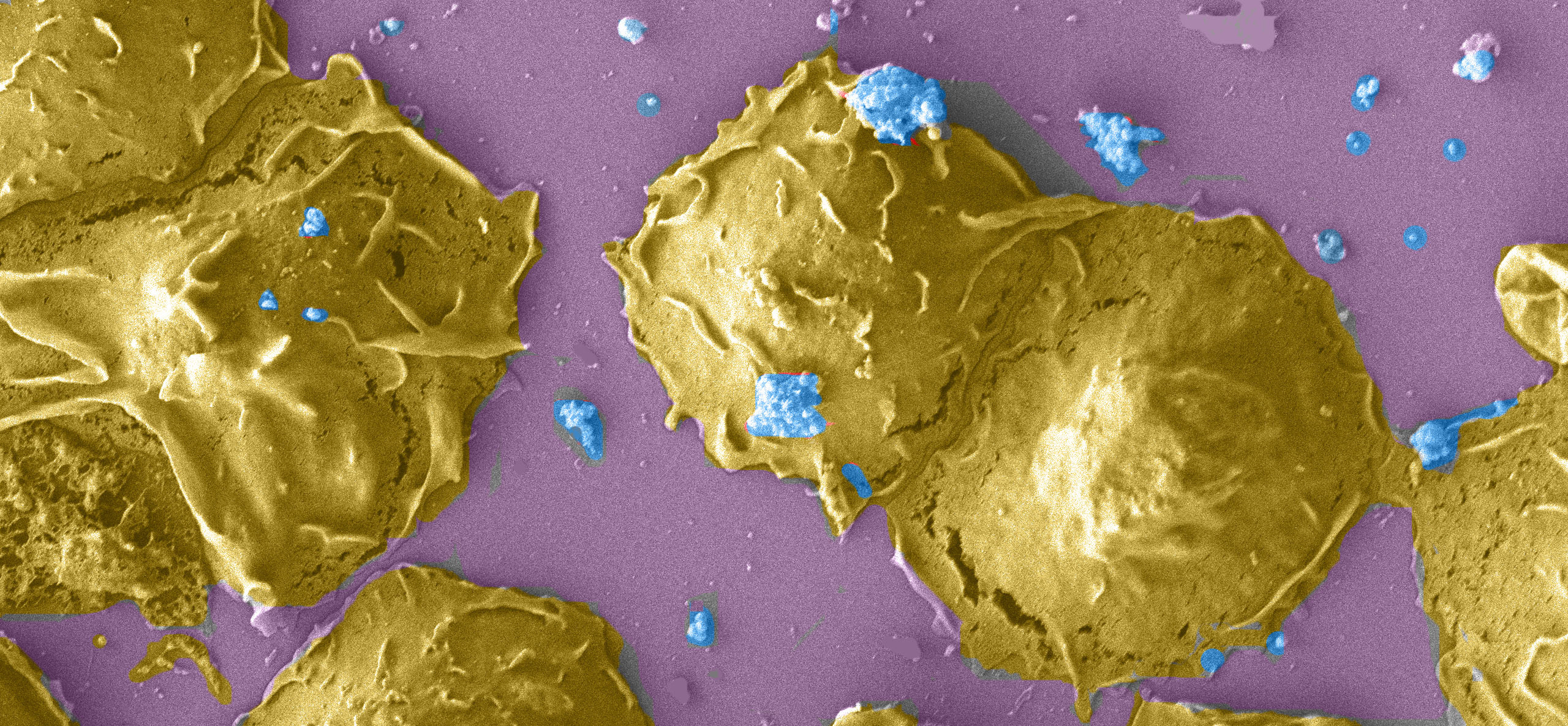

Chlamydia trachomatis being the most common cause of sexually transmitted disease, accounting for infecting 130 million people every year has its own strategy to keep the infection silent. We found the pathogen once sees the immune system of the host paralyses the first line of defense, the neutrophils. Humans have evolved the immune system to fight and contain high infectious load that they encounter every day by generating inflammatory responses. Neutrophils are known to recognize the pathogens early enough to respond and clear off infection. Approximately 100 billion neutrophils enter and leave circulating blood every day. Chemokines, small signaling molecules are potent chemoattractants for neutrophils to sites of infection. Migration toward the site of infection involves a complex multi-step process, including rolling adhesion of neutrophils on endothelial cells, firm adhesion of neutrophils, extravasation through the endothelium, and chemotactic migration.

Chlamydia infection is known to activate the production of various cytokines that attract massive infiltration of neutrophils to the site of infection. Upon migration to the site of infection, normally the neutrophil eliminates the invading pathogen utilizing a combination of NADPH oxidase derived reactive oxygen species, cytotoxic granule components, and neutrophil extracellular traps (NET). Although Chlamydia infection attracts neutrophils, the infection is not controlled and shows limited inflammation. We reveal how this pathogen ‘tames the killer’ and even renter them ineffective and silent towards any pathogen. Once the neutrophil encounter Chlamydia it looses its activity to recognize and react to other microbes, thus mimicking a neutropenic condition or immune-compromised situation, which is alarming. One such situation is very well observed in clinical interventions: that chlamydia infections are associated with co-infections with pathogens like Neisseria Gonorrhoeae and HIV.

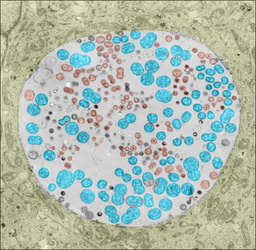

Pathogens inhibition NETs release by down-regulating host inflammatory responses; degradation of NETs using pathogen-derived DNases; and resistance to the microbicidal components of NETs, which involves a variety of mechanisms, including encapsulation. Many pathogens like Staphylococcus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Aspergillus fumigatusare know to prevent neutrophil activation by secreting virulence factors, which are proteases, and nucleases that digest the Neutrophils extracellular traps. Chalmydia, prefer epithelial cells for its replication and when it lyse open to infect neighboring cells, would encounter immune cells. They secrete the cysteine protease called CPAF (chlamydial protease-like activity factor), a serine protease effectively fine tunes the killers and render the neutrophils paralyzed. Neutrophil that are exposed to chlamydia looses its ability to react to infections, moreover we found that chlamydia even hijack the neutrophils and replicate in a certain population.

Thus this study reveals how Chlamydia exploits our immune system and uses it to establish itself. This knowledge is applicable outside of the research settings and may have implications for policy to tackle this epidemic and would help to effectively develop therapeutic interventions against this epidemic.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in