Turning a Bug into a Feature: The Story of Polymerase Strand Recycling (PSR)

Published in Bioengineering & Biotechnology

Cell-free systems' versatility and modularity make them excellent platforms for biosensor development. When I joined the Lucks Lab in early 2021, there was a recent publication on the development of ROSALIND—a cell-free platform to detect water contaminants. I wanted to build on this technology and improve the biosensing sensitivity by leveraging knowledge from DNA nanotechnology to detect targets at regulatory standards. This project brought us to what seemed like a problem, but what we turned into an opportunity: Polymerase Strand Recycling (PSR) [1].

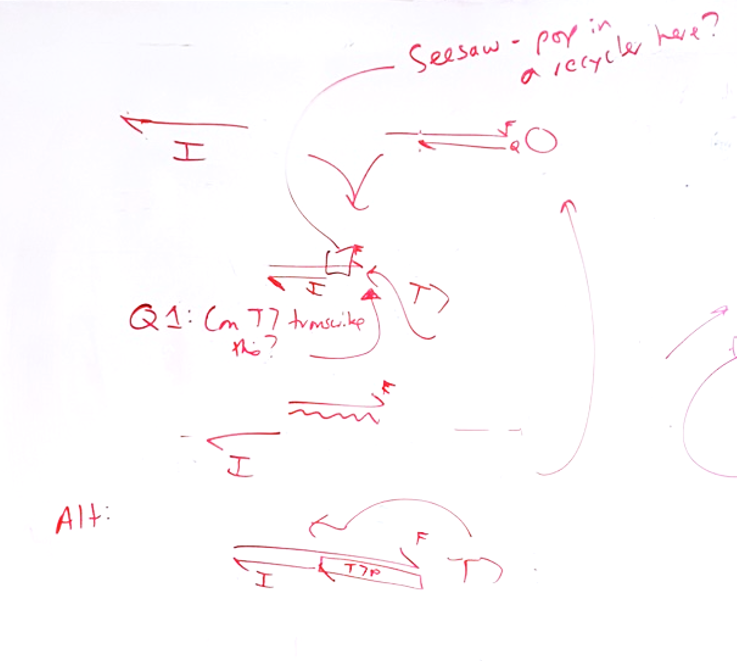

The inspiration for PSR stemmed from an annoyance. T7 RNA polymerase, the crucial driver of cell-free reactions, has a tendency to transcribe from DNA duplexes with exposed 3’ toeholds. This off-target transcription can derail carefully designed DNA strand displacement circuits, making them incompatible with many biosensor systems, and also incompatible with cool tricks from DNA nanotechnology like signal amplification we wanted to play around with [2]. After months of failed experiments and frustration, Julius and I went back to the whiteboard to brainstorm new designs. We were tired of working against T7 RNA polymerase off-target activity, but what if we could flip this bug into a feature? Could we harness this behavior to create a new type of signal amplification circuit?

That’s where PSR was born. The core idea is simple: use T7 RNA polymerase’s off-target transcription to recycle DNA strands in a controlled, autocatalytic cycle. This allows one DNA strand to generate multiple rounds of signal, amplifying the output of a biosensor reaction without needing extra steps or equipment. We were excited to test out this new circuit feature. If it worked, this could be a game-changer for boosting biosensor sensitivity.

Turning Concepts into Circuits

Building PSR into a biosensor involved three layers: sensing, processing, and amplification. The sensing layer detects the target molecule, such as a small molecule or RNA, and generates an initial RNA signal. The processing layer converts this RNA signal into a recyclable DNA strand. Finally, the amplification layer—the PSR core—leverages T7 RNA polymerase to regenerate this DNA strand, driving repeated rounds of signal generation.

The first experiments tested the concept using DNA-DNA and RNA-DNA duplexes. We quickly learned that PSR only works efficiently with DNA-DNA duplexes, as RNA-DNA hybrids inhibit transcription. This discovery pushed us to design an intermediate “fuel gate”, which converts RNA signals into DNA, enabling amplification. With this new circuit design, for the first time, we saw fluorescence signals amplify dramatically with low amount of input and minimal fluorescence leak in the absence of input.

Signal Amplification

We wanted to apply PSR to detect different types of circuit inputs to demonstrate the versatility of this new circuit. First, we tested it with direct RNA imputs, achieving limits of detection in the nanomolar range for microRNAs, important biomarkers for health diagnostics. Around this time, Tyler Lucci, another student in the lab showed through modeling that signal amplification could lead to a boost in sensitivity for biosensors. (You can see the details of the model in the paper!). To test this out, we moved to transcriptional biosensors regulated by allosteric transcription factors (aTFs). By implementing PSR in biosensors for tetracycline and zinc, we demonstrated a 10-fold improvement in sensitivity, demonstrating that the model was correct, and hitting detection limits relevant to environmental and regulatory needs.

Freeze-Dried and Field-Ready

One of the most satisfying moments was seeing our PSR-enabled biosensors freeze-dried and rehydrated for field use. By optimizing lyophilization protocols, we preserved the biosensors’ functionality in unprocessed environmental samples like Lake Michigan water. This was a big step forward in making the technology accessible for point-of-care diagnostics.

Looking Ahead

PSR is just the beginning. Its modularity means it can potentially integrate with other nucleic acid computation systems, paving the way for even more sophisticated circuits. Reflecting on this journey, I’m struck by how turning a “bug” into a “feature” can lead to innovation. Developing PSR showed me that challenges and chaos can inspire creativity and that the quirks of biological systems can be harnessed for innovation.

For more information about PSR and its application to biosensing, check out the paper https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-024-01816-w.

References

- Li, Y., et al., A cell-free biosensor signal amplification circuit with polymerase strand recycling. Nature Chemical Biology, 2025.

- Li, B., A.D. Ellington, and X. Chen, Rational, modular adaptation of enzyme-free DNA circuits to multiple detection methods. Nucleic Acids Res, 2011. 39(16): p. e110.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Chemical Biology

An international monthly journal that provides a high-visibility forum for the chemical biology community, combining the scientific ideas and approaches of chemistry, biology and allied disciplines to understand and manipulate biological systems with molecular precision.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in