A slice of calm: Mindfulness can reduce stress

Published in Neuroscience and Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

A 2023 editorial published in Nature Mental Health1 called for evidence for “establishing the effectiveness of individual mindfulness-based interventions” because existent studies do not include active control conditions, have low sample sizes which result in “underpowered studies and findings that cannot be replicated”, and use cross-sectional designs that “preclude determining causality and highlight the need for randomized clinical trials”. As part of a PhD project started in 2019 and jointly supervised by researchers at Swansea University (UK), Université Grenoble Alpes (France), and Charles University, Prague (Czech Republic), we designed a study that integrated exactly these aspects. We tested whether mindfulness exercises are truly effective in reducing stress and which types of exercises might work best, using experimental psychology methods and 2239 participants over 37 data collection sites.

What do we think mindfulness is?

Mindfulness meditation, popularized in the West by Jon Kabat-Zinn in the 1970s, is not only ubiquitous and prescriptive, but also polarizing: it is alluring to some and completely unappealing to others. Defined simply as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally” (Kabat-Zinn, 1994), its health benefits are rather well-documented. Despite this, mindfulness is too often seen in a utilitarian light—as a tool to replace medication, promote calmness, boost focus, enhance creativity or performance, make us better students, partners, parents, leaders, etc. This perspective and the widespread prescription of mindfulness in workplace settings shift the responsibility for well-being from structural/organizational factors to individual efforts, adding to pressure on employees to 'feel good to do good'.

While mindfulness meditation can be beneficial, its accessibility is often limited by cost, time, and the mental space required for practice. Commercialized mindfulness tools, such as smartphone apps and self-help books, have recently become popular and extremely lucrative. They offer a more affordable and convenient alternative to professional classes, allowing individuals to practice at their own pace and in their own space, which is particularly appealing in the current economic climate where the cost of mental healthcare has risen. However, this convenience comes with limitations, as the efficacy of self-administered mindfulness exercises has not been thoroughly investigated. Our study aimed to address this gap and make mindfulness more rigorously evaluated.

Advancing mindfulness research

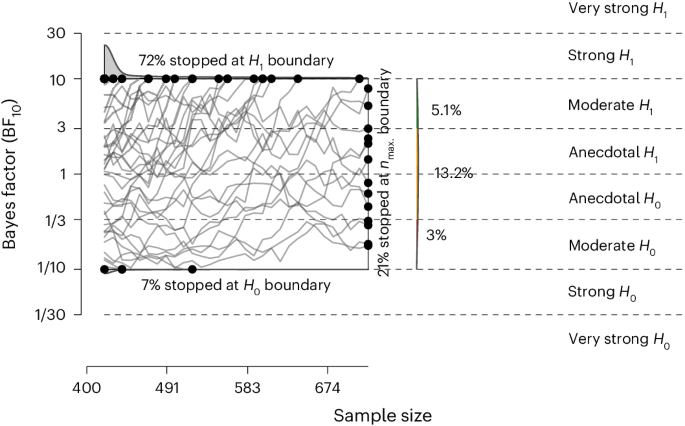

We designed a randomized-controlled study that was adequately powered and pre-registered. This study is a significant advancement, being the first high-powered experimental test of self-administered mindfulness in reducing acute stress levels. Participants completed, at home, the 15-minute mindfulness meditation session recorded by a certified instructor. They were randomized to one of four different exercises: For ‘Body Scan’, they "scanned" parts of their body, returning their awareness to the body part whenever their mind wandered. For ‘Mindful Breathing’, they focused on their breath, returning their attention to it with kindness and patience whenever their mind wandered. For ‘Loving-Kindness’, participants directed loving-kindness towards themselves and others, while for ‘Mindful Walking’ they walked in a quiet place, bringing awareness to the sensations of walking and the contact of their feet with the ground.

Participants reported their stress levels after the exercises, and we found that all four exercises were slightly more efficacious in reducing participants’ stress than listening to a story excerpt as an active control condition. This suggests that short, self-administered mindfulness exercises can provide immediate stress relief, which is particularly valuable in high-stress situations where quick mood regulation is needed.

While our study provides robust evidence for the effectiveness of self-administered mindfulness exercises, some limitations need to be acknowledged. Our findings may not be generalizable to populations different from our sample, that included students from affluent countries fluent/native English speakers, non-meditators, and without a history of mental illness. Ethically speaking, participants needed to be informed that they might take part in mindfulness meditation in order to safeguard them from potential adverse effects2 mindfulness can have, although informing them might have increased demand effects. Finally, the effects of each exercise on stress reduction were relatively small and relied on self-reports. Future studies should incorporate more objective measures, such as neurocognitive or physiological assessments of the autonomic nervous system (e.g., catecholamines, skin conductance, cortisol, blood pressure), to corroborate and complete our findings.

We conducted this project transparently, from pre-registering its protocol, hypotheses and analysis plan on the Open Science Framework (OSF) platform, to sharing the code, data, and the peer-reviews. This transparency contributes to the reliability and the potential for reproducibility of our findings. In the same ethos, we believe that it is important to consider what our research does not show: We do not claim that a 15-minute mindfulness exercise has the same effects as prolonged practice. Learning to practice mindfulness in a shorter time than traditional protocols typically require can be a valuable asset for people for whom longer time commitment for mindfulness is a capacity- or a motivation-based deterrent – and might help level up existent inequalities in mental health.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates the effectiveness of short, self-administered mindfulness exercises in reducing stress, providing a valuable tool for short-term mood regulation. Situations in which we need to get a quick grip on our emotions are frequent: calming oneself in a road-rage situation or a relationship argument can be a deal breaker for conflict de-escalation. Short mindfulness exercises can be valuable for building up one’s repertoire of such short-term mood regulation skills. They can help us get better at paying attention to what helps us solve the conflict, or at understanding that the situation is not necessarily adversarial. The findings are particularly relevant in the context of the increased mental health challenges exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. While our study focused on a specific population and short-term effects, it highlights the potential of mindfulness as a practical, accessible intervention for stress management. Future studies should compare this shorter-term benefit with prolonged practice. Any tool that may help people learn such skills can be valuable elements for mood regulation, be it short- or longer-term. By advancing our understanding of the efficacy of mindfulness and addressing the limitations of previous research, our study contributes to the growing evidence base supporting mindfulness practices.

References:

Original cover art by Inês-Hermione Mulford.

1 Mindfulness research needs an intervention. Nat. Mental Health 1, 437–438 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-023-00100-5.

2 Britton, W. B., Lindahl, J. R., Cooper, D. J., Canby, N. K., & Palitsky, R. (2021). Defining and measuring meditation-related adverse effects in mindfulness-based programs. Clinical Psychological Science, 9(6), 1185-1204. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/2167702621996340?journalCode=cpxa

Contributors:

Dr Alessandro Sparacio is research scientists at A*STAR, specializing in mental health and stress research. He holds a PhD from Universite Grenoble Alpes and Swansea University, where he conducted work on mindfulness and the evaluation of efficacy of other stress reduction strategies.

Dr Gabriela Jiga-Boy is Senior Lecturer (Associate Professor) in social psychology at Swansea University's School of Psychology (UK). Her research interests are trust in politics and new technologies, social norms and behaviour change, from both social cognition and inter-group behaviour perspectives. She teaches behaviour change and research methods.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Human Behaviour

Drawing from a broad spectrum of social, biological, health, and physical science disciplines, this journal publishes research of outstanding significance into any aspect of individual or collective human behaviour.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Digital Media and Mental Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Apr 15, 2026

Basic Psychological Needs and Well-Being

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Nov 27, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in