A unifed global genotyping framework of dengue virus serotype-1 for a stratifed coordinated surveillance strategy of dengue epidemics

Published in Microbiology

Dengue, caused by dengue virus (DENV) infection and mainly transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, is now considered the most prevalent arboviral disease in human, and it circulates predominantly in tropical and subtropical regions, with more than half the world’s population at its risk. Dengue was listed in "Ten threats to global health in 2019" by the World Health Organization.

Urbanization, climate change, and globalization including rising global tourism are re-shaping the phylogeographic structure of virus populations, possibly contributing to a succession of severe viral pandemics as an unprecedented challenge to global public health. To investigate viral dispersion mechanisms in phylogeography and phylodynamics, various analytical methods and general genotyping methods have been developed for more accurate pathogen identification beyond viral species. Recently, the high-resolution genotyping scheme for surveillance manifested itself to be powerful in rapidly tracking the active lineages and transmission chains of SARS-CoV-2. Even though disease burden assessment and prediction using mosquito ecological data and dengue epidemic data have been investigated globally, there is still lack of a systematic scheme for understanding the DENV population structure, dynamics and mechanisms of cross-national, cross-regional, and even cross-continental transmission in a global profile.

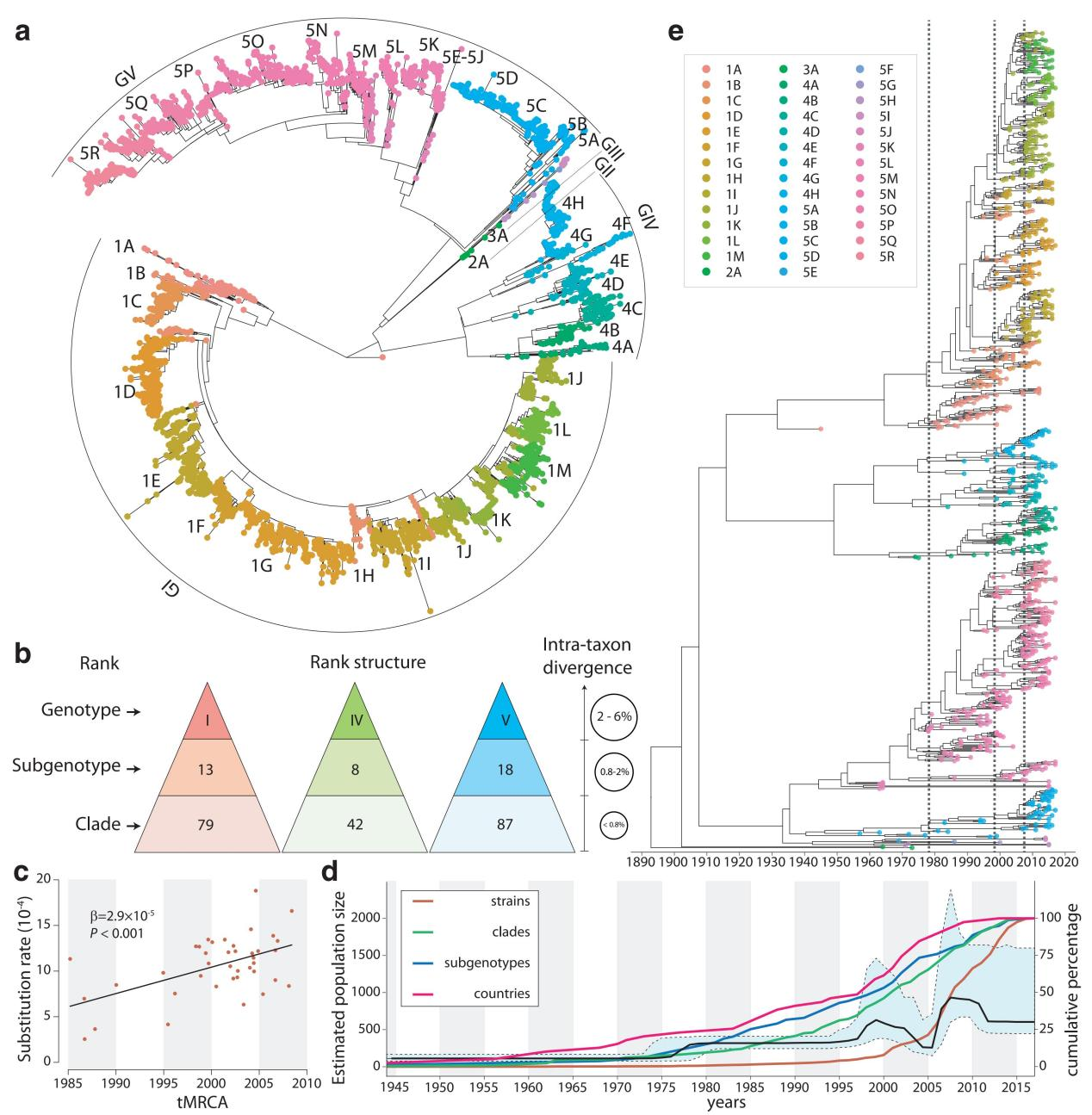

Targeting DENV-1 spreading prominently in recent decades, by reconciling all qualified complete E gene sequences of 5003 DENV-1 strains, with the relative epidemiological information confirmed by literature research, from 78 epidemic countries/areas ranging from 1944 to 2018, the present study has established a unified global high-resolution genotyping framework of DENV-1 designating three hierarchical layers of clade, subgenotype and genotype with respective mean pairwise distances (MPDs)≦0.8%, 0.8-2%, and 2-6%.

Global genotyping framework of DENV-1 established based on its population structure, phylogeny, and epidemiology.

Figure 1 of the paper by Li et al.

On the one hand, the global epidemic patterns of DENV-1 showed strong geographic constraints representing stratified spatial-genetic epidemic pairs of Continent-Genotype, Region-Subgenotype and Nation-Clade. Thereby 12 epidemic regions have been identified including: GMS-China, Great Mekong Subregion-China; SEA, Southeast Asia; PHI, Philippines; TWP, Tropical Western Pacific; OCE, Oceania; WAFR, West African Region; RSR, Red Sea Region; SWIO, Southwest Indian Ocean; SASC, South Asia Subcontinent; CNA, Central North America; CAR, Caribbean; and SA, South America, which prospectively facilitates the region-based coordination. As for the pair of the Region-Subgenotype, 92.3% and 71.8% of the 39 designated subgenotypes, with ≥50% and ≥80% isolates respectively, mainly circulated in a single region.

On the other hand, the present study also reminds us to be concerned about the cross-regional and even cross-continental diffusion of DENV-1, which potentially arouse large epidemics, in reference to the stratified spatial-genetic epidemic pairs. For example, several subgenotypes including 5K, 5B, 4F, 5C, 5M and 5N were found spreading across several regions. The cross-regional transmissions were mostly observed in adjacent regions, especially in the regions of Asian or American Continents, but only a few cross-continental transmissions occurred. Collectively, the transmissions of subgenotypes cross countries/regions, on the rise in recent decades, can explain its continuous global expansion to some extent. Therefore, international collaborations based on the framework in promptly pinpointing and periodically updating the hotspots of emerging, transmission, drifting, and replacement of DENV-1 will give rise to cost-effective surveillance strategy for regional and global control of dengue.

In addition, through in-depth explorations of the global transmission pattern of DENV-1 using this framework, we observed that the traditional endemic countries such as Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines, India, and Brazil apparently displayed as the persisting dominant source centers, while the emerging epidemic countries such as China, Australia, and the USA, where dengue outbreaks were frequently triggered by importation, showed a growing trend of DENV-1 diffusion. Meanwhile, the singletons in subgenotypes (12/41) and clades (63/208) recognized in our study suggest that they may be partially caused by widely deficient surveillance. The probably hidden epidemics were found especially in Africa and India. Then, our framework can be utilized in an accurate daily coordinated surveillance based on the population compositions of its clades and subgenotypes, which is prospectively valuable for hampering the ongoing transition process of epidemic to endemics and addressing the issue of inadequate monitoring.

The genotyping framework and its utilization in quantitatively assessing DENV-1 epidemics has laid a foundation and re-unveiled the urgency for establishing a stratified coordinated surveillance platform for blocking global spreading of dengue. This framework is moreover expected to bridge classical DENV-1 genotyping with genomic epidemiology and even pathogen-mosquito-disease-associated risk modelling. The authors will promote the public availability to the framework and keep periodic updating of it as well.

Graphical abstract of the paper by Li et al.

https://idpjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40249-022-01024-5

Follow the Topic

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Urbanization and Infectious Diseases

A thematic series in Infectious Diseases of Poverty.

We are experiencing the process of global large-scale urbanization and nearly 70% of the world’s population will live in urban areas by 2050 according to the World Urbanization Prospects issued by the United Nations. Urbanization has the pros and cons like a double-edged sword. Improved health services, better infrastructure and more employment opportunities benefit people a lot, but the overcrowding, environmental pollution, dietary changes and traffic jam may cause health problems.

Non-communicable diseases have attracted researcher’ concern due to its increasing importance during the process of urbanization (e.g., cardiovascular disease, diabetes, mental health, hypertension, obesity), but the communicable diseases seem to be neglected. The ongoing global pandemic caused by COVID-19 warns us again about the potential threats from infectious diseases, the wide connectivity, heightened mobilities and potential zoonotic risks from rapid urbanization became immediately apparent for human health. For low-income countries, infectious diseases still have a profound impact since the leading morbidity and mortality are still infectious diseases and many of those low-income countries will have a major growth among urban population in the future. Urbanization can result in an amount of changes such as the environment, climate, biodiversity, wildlife habitat, social and spatial aspect, human behavior and population movement and land-use, which will re-shape the (re)emergence and trajectory of infectious diseases, both human diseases and zoonotic diseases contributing to the occasionally cross species spillovers from wildlife populations to humans.

As a complex dynamic process, urbanization is associated with human, domestic poultry, wild birds, environment and even expanded interfaces of contacts among them, which may all result in increased vulnerability to infectious disease. Besides, due to different urbanization process, social class and educational level, the influence of urbanization on infectious diseases will be very heterogeneous and the local diseases and health challenges can greatly differ. Hence, a multi-disciplinary and multi-sectoral approach including epidemiology, geography, sociology, ecology, zoology, veterinary science, statistics and others is needed to better illuminate the relationship between urbanization and infectious diseases.

In order to better understand the impact of urbanization on infectious diseases and provide rational policy suggestions on improving human health, the journal of Infectious Diseases of Poverty is launching a new Thematic Series entitled Urbanization and infectious diseases. This series will focus on better evidence of impacts of the urbanization process on various infectious diseases, included but not limited to vector-borne infectious diseases, water-borne diseases, food-borne diseases, natural focus disease or endemic disease, respiratory diseases, zoonotic diseases and emerging infectious diseases.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Ongoing

Role of Vaccines in the Elimination of Infectious Diseases of Poverty: Need for Innovation and Development

There is a great need for preventing infectious diseases of poverty, a group of diseases that disproportionately affect the world’s poorest populations, exacerbating cycles of poverty and poor health. They are highly prevalent in low-income and marginalized communities and closely associated with inadequate access to healthcare, poor sanitation, malnutrition (including vitamin A deficiency) and limited resources for prevention and treatment. Reference is made to a broad range of viral diseases, such as measles, dengue fever, rotavirus, but also bacterial (tuberculosis (TB) and cholera), protozoal (malaria, leishmaniasis and Chagas) as well as the large number of common worm infections: soil-transmitted helminth infections (STH), strongyloidiasis, schistosomiasis, food-born trematodiasis (FBT), lymphatic filariasis (LF), cysticercosis and echinococcosis.

Many of these diseases, in particular those caused by worms, are currently controlled by preventive chemotherapy, while some viral infections can be averted by vaccines. A wider spectrum of vaccines is needed, including agents directed against diseases that are currently controlled by drugs. Work on understanding the biology of the many different pathogens requires innovative technologies to overcome challenges such as pathogen variability and immune evasion, while simultaneously keeping safety standards high. In addition, the end product must be manufactured at scale and distributed efficiently while at the same time be affordable, something that faces logistical challenges in resource-poor settings.

To control poverty-related infectious diseases, vaccines must be accessible to those who need them most. They contribute strongly in the multifaceted endeavour for controlling and eventually eliminating the infectious diseases of poverty, but require a combination of scientific innovation, strategic planning and equitable access to make a significant impact on global health. Indeed, vaccines are critical in the fight against diseases in low-income countries, offering a cost-effective and efficient means of preventing illness, saving lives and promoting global health equity.

So far, smallpox is the only human infection that has been eradicated but polio is not far behind. This promises further progress creating and implementing immunizations that target other widespread infections. While knowledge of specific cytokine responses, and the antibodies they elicit, assists the choice of which antigens to focus on for vaccine development, novel adjuvants contribute to selective manipulation of the immune response. Importantly, the drug-related control of the worm infections can be prolonged if complemented with vaccines preventing reinfection. Repositioning of vaccines within the total infectious disease scenario through the combined use of chemotherapy and vaccination would thus be a versatile approach to control and elimination of infectious diseases of poverty.

This thematic series aims to trigger more research on areas including (i) Screening to find more vaccine candidates that can effectively trigger a protective immune response, (ii) Clinical trials to move potential vaccines towards Phase 1, Phase II and eventually Phase III testing while ensuring both safety and efficacy, (iii) Manufacturing and Distribution to make sure that verified products can be quickly manufactured at scale and distributed efficiently, (iv) Policy and Advocacy to promote the deployment of affordable vaccines to the populations most in need of them through enhanced funding for vaccine research and extensive vaccination campaigns. In this way, the proposed series will address the unique challenges of poverty-related infectious diseases ensuring that vaccines are not only developed but also reach those who need them.

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 3, Good Health and Well-Being.

All submissions in this collection undergo the journal’s standard peer review process. Similarly, all manuscripts authored by a Guest Editor(s) will be handled by the Editor-in-Chief. As an open access publication, this journal levies an article processing fee (details here). We recognize that many key stakeholders may not have access to such resources and are committed to supporting participation in this issue wherever resources are a barrier. For more information about what support may be available, please visit OA funding and support, or email OAfundingpolicy@springernature.com or the Editor-in-Chief.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Feb 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in