Educated microbes

Published in Microbiology

“Once a microbe has been thus educated to resist a drug, it does not lose this property very quickly…”

Sir Alexander Fleming on the 'Discovery of Penicillin', recorded by the BBC on 28 August, 1945.

This audio recording of Sir Alexander Fleming welcomed me to “Superbugs: the fight for our lives”, a special exhibition at the Science Museum in London. The space is dedicated to raise awareness among the general public about the global health threat posed by the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (aka “the superbugs” for many, or the “educated microbes” for Fleming*) and highlight some of the many ways used to tackle this problem.

First-hand encounters

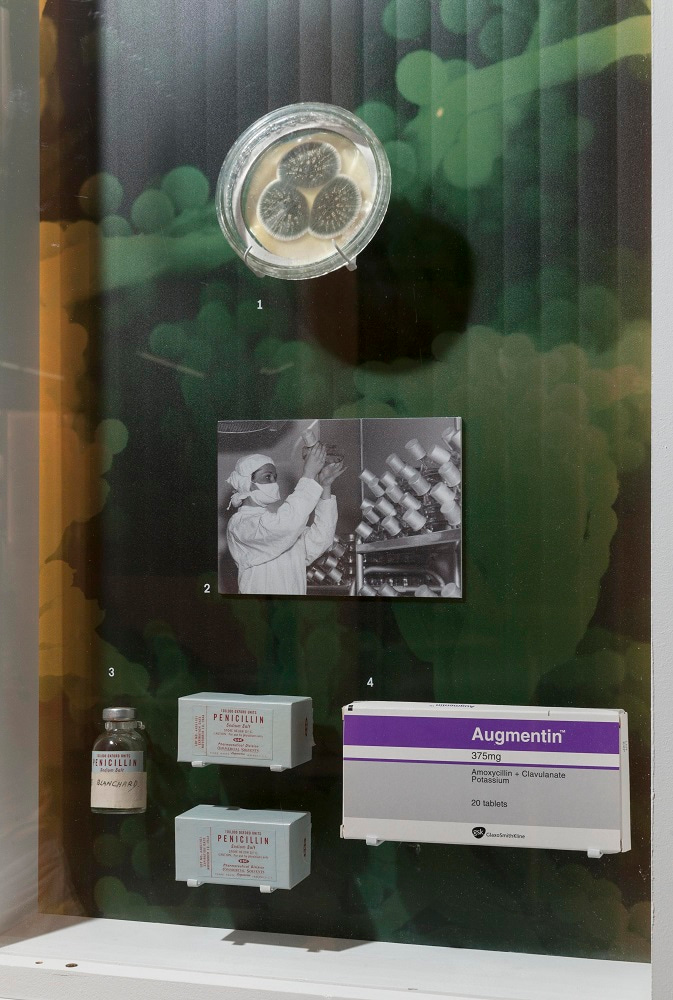

Tucked in a corner of the “Tomorrow’s World” gallery at the back of the museum, and right across from one of its main restaurants, the exhibit may initially go unnoticed. But then your eyes will eventually catch the big capital letters – S-U-P-E-R-B-U-G-S – and by then it’s hard to stay away. Because there’s no dedicated entrance or exit, you also have to make your own way around the space, which makes it all more interesting. While wandering, and after hearing about the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) problem from Fleming himself, I then came across real agar plates containing some of the world’s most problematic bacteria, including the likes of MRSA (methycilin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) and other ESKAPE pathogens (don’t worry, I’m told they are dead and stored in sealed containers, and there was even a discussion on whether these are real plates or pictures...). Next to Fleming’s recording (and brief history of penicillin) there’s also a Penicillium mold grown recently from Fleming’s original sample (which is conveniently located at the Science Museum), perhaps intentionally placed there to remind us that not all things that grow on plates are necessarily bad.

Agar plates containing Superbugs

(courtesy of the Science Museum)

A history of penicillin, including a fresh Penicillium mold grown from Fleming's original sample.

(courtesy of the Science Museum)

Perhaps more impressive than seeing the plates that encapsulate our enemies on this fight were the encounters with people on our side of the trenches, including those who faced the problem of antibiotic-resistant infections first-hand. That’s the case of Geoffrey Pattie, a cancer patient who in a video tells us the story about how while undergoing a surgery he contracted an infection with a strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae that was resistant to all currently used antibiotics, and as a result was left unconscious for 6 weeks and spent a total of five months in a hospital isolation ward to prevent his infection from spreading. A nearby display showcases the 14,000 pills that each individual must take during the two-year treatment needed to fight drug-resistant tuberculosis (for more, see here). Even for someone familiar with the AMR problem and with drug-resistant tuberculosis, these displays help to frame the issue in a different light, not one of number of cases and economic cost, but rather as a problem that affects people. Such a personal perspective is hard to ignore, particularly as one is then reminded that AMR today kills approximately 700,000 people annually and is projected to affect up to 10 million individuals every year by 2050 (that’s the whole population of a country the size of Portugal). To add to this sombre setting, the exhibit then highlights how we’re all part of the problem, cleverly displaying interviews that showcase how the general public often misunderstands antibiotics and their use, including by pushing doctors to overprescribe unnecessary pills or by taking them incorrectly. The final strokes in this gloomy picture come with the information that in this day and age antibiotic-resistant bacteria know no borders, so the AMR crisis truly is a global health problem.

Bacteria without borders display, including a box enclosing the 14,000 pills required for a single two-year treatment to fight drug-resistant tuberculosis.

(courtesy of the Science Museum)

Reasons for optimism

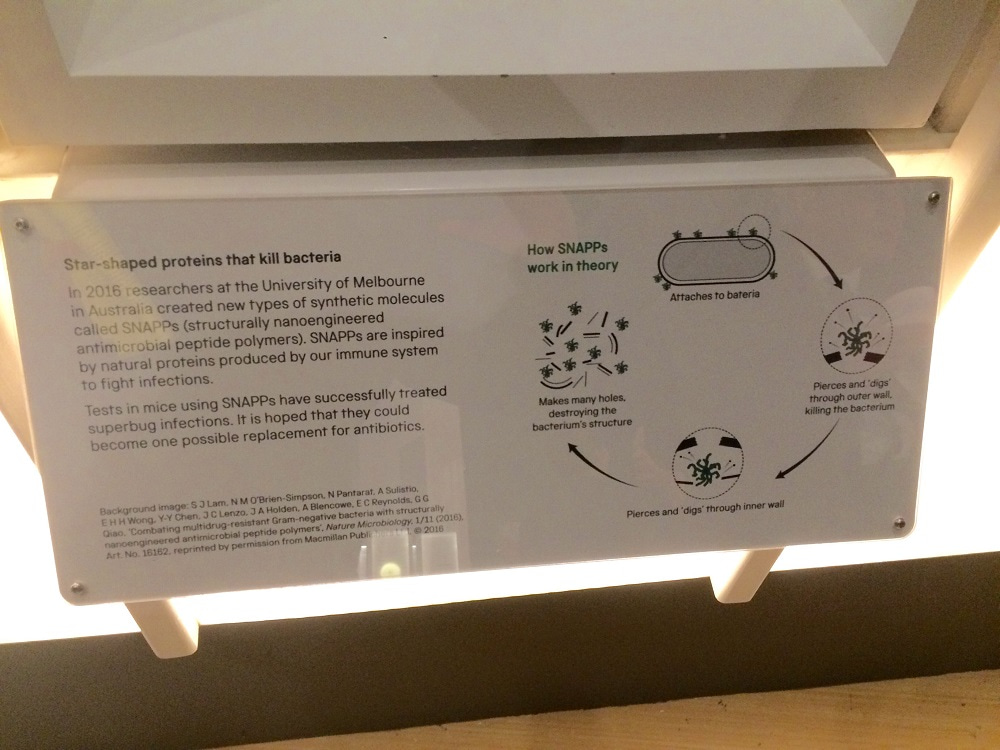

But it’s not all bad news. After setting the stage for a potential post-apocalyptic world where current drugs don’t work**, the rest of the exhibition showcases some of the steps being taken to tackle the problem. As a microbiologist, it was particularly rewarding to see basic research featured prominently on the walls, including studies exploring phages and predatory bacteria as alternative strategies to kill bacteria (yes, there is a whole section on Bdellovibrio). As part of the Nature Microbiology team, the highlight is clearly a section on SNAPPS (structurally nanoengineered antimicrobial peptide polymers) and how they are effective against Acinetobacter baumannii infections – you can read the full paper in our pages. On top of these alternatives to antibiotics, another section is dedicated to current efforts aimed at finding new antimicrobials, with a shout to the use of the iChip to discover teixobactin or the exploration of unusual sources - such as Komodo dragons, Icelandic fjords and Brazilian leafcutter ants - to find new drugs.

Star-shaped proteins that kill bacteria.

(courtesy of Andrew Jermy)

New ways to find antimicrobials, including the iChip (left), Komodo dragon blood (top right) and Brazilian leafcutter ants (bottom right).

(courtesy of the Science Museum)

Importantly, we’re all reminded that the fight against AMR extends well beyond the laboratory and finding new ways to kill bacteria. The need for this collaborative effort is personified and presented in the form of an MD discussing the need to stop over-prescribing antibiotics; a nurse explaining how to prevent dissemination within health-care settings; a designer developing new materials that prevent bacterial spreading; and a farmer highlighting the need to reduce the amount of drugs used in livestock (illustrated by a personal favourite, a pig filled with pills). A display of prototypes competing to win the Longitude Prize ensures that the need for new “affordable, accurate, fast and easy-to-use” diagnostics for bacterial infections isn’t forgotten either. And the importance of economics is also touched upon by the means of an interactive game where you can take up the role of the head of a global health organization and try to halt the spread of a drug-resistant bacterium by investing on diagnosis, health campaigns or the development of new drugs, while keeping to a tight budget.

People waging war on the superbugs.

(courtesy of the Science Museum)

A pig with pills.

Ignorance is bliss

In the end, “Superbugs: the fight for our lives” fulfils its goals of raising awareness among the general public to the problem of drug-resistant bacteria, not only from a medical and scientific perspective but also (and perhaps more importantly) by showcasing how AMR affects people’s lives. I also found it somewhat comforting that overall the exhibition stays away from the “post-antibiotic apocalypse” theme that often characterizes discussions on the topic, and rather provides a nice balance between the real problems we currently face today and many of the potential solutions being developed to fight back against these educated microbes. By presenting a multidisciplinary approach that encompasses basic researchers, drug developers, health-care practitioners, engineers and members of the general public, it is also clear that scientists are a critical part of the solution but that we’re all on this together and collaboration across fields is crucial. The use of a wide range of media types, from bacterial plates to videos and interactive games, helps to bring different audiences on board and ensures that there truly is something for everyone. And if each of the three million visitors that the Museum gets every year walks out knowing a bit more about drug-resistant bacteria and just remembers that not all infections require antibiotics, we can start to envision a future where the microbes may be ignorant once again – either to the drugs we have now or potentially even new ones.

The exhibition is free and open daily from 9 November 2017 until spring 2019 and will then go a world tour.

* I really dislike the term superbug, mostly because I feel it doesn’t even work well for getting the main point across. The “super” prefix is commonly used as “a generalized term of approval” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/super) – just think of Superman, who isn’t a particularly nasty man, he is just super human, mostly in a cool way… So for me “superbugs” should be used to refer to those microorganisms that are even better than most – say, when you engineer bacteria to produce an antibiotic (http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/1/4/e1500077) or make biofuels – rather than to indicate those that are special for a particularly terrifying feature. A quick poll of the editors around me confirmed that they also think “super” has mostly positive connotation (and that no one likes the use of “bugs” to refer to microorganisms), although it has been pointed out that the prefix is also used in supervillains… In any case, antibiotic-resistant bacteria works much better, but it is long and can get tedious, so every once and a while I'll go with Fleming and use “educated microbe” for a change.

** I’m not a big fan of fearmongering, particularly when it comes to serious problems. This has been a particular feature of the AMR discussion every once and again with terms like superbugs, post-antibiotic apocalypse, and the like being thrown around. But even though sometimes the exhibition seems like it could go down that route (particularly when it comes to the title), overall it really doesn’t and instead provides a factual account of the problem faced nowadays and offers many potential solutions, so I left feeling rather optimistic about our chances to win the fight.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in