Exploring and sharing the ‘collective memory’ stored at the bottom of the ocean

Published in Ecology & Evolution

Explore the Research

Nature - Not Found

Sorry, the page you requested is unavailable. The link you requested might be broken, or no longer exist.

It all started with a need to understand how phytoplankton evolve in the rapidly changing marine ecosystem. What do we actually know about the potential of phytoplankton to adapt to change, such as global warming as it occurs in nature? Based on previous experimental work, the adaptive potential of these single-celled oxygen producers in the ocean seem rather high. In a quest to explore this understanding in natural conditions and to convey new knowledge about a realistic pace of evolution, we set out on a transdisciplinary journey.

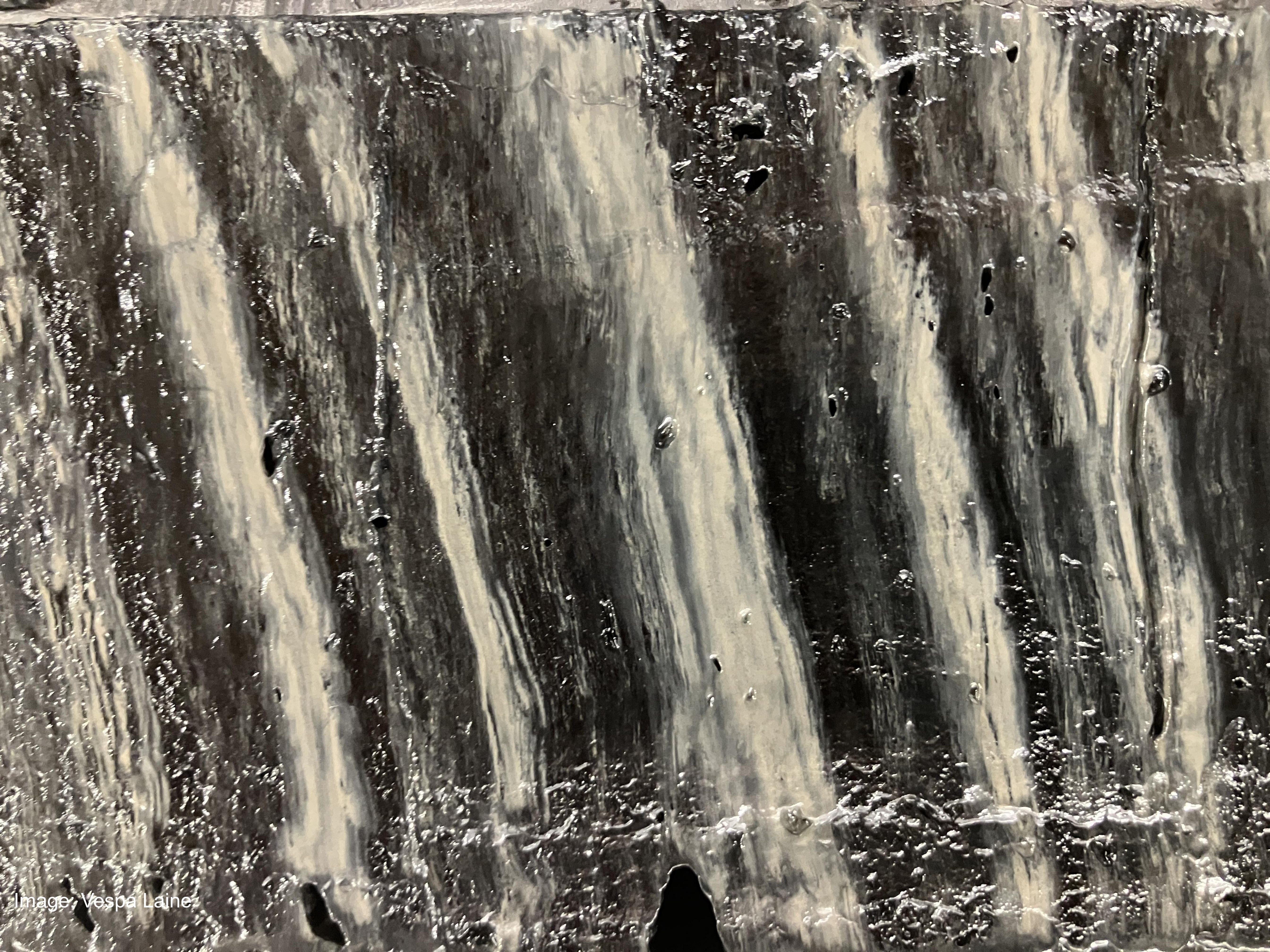

The cold, dark, and sometimes oxygen-free bottom of the ocean hosts an incredible hidden archive of fossils of microorganisms and signs of past environmental changes. Despite the hostile conditions, the muddy, vertically layered sediments containing yearly depositions from the water above also encompass life, albeit it being deep asleep. As we resurrected sleeping phytoplankton cells from the bottom of the ocean, the oldest originating from the 1960s, we had entered a collective memory that was suddenly tangible in our laboratory. Seeing growing cells under the microscope, cells originating from organisms that previously had thrived in the ocean more than 60 years ago sparked a deep urge to study them in more detail. In addition, it has inspired our artist colleagues to join us in decrypting messages from the past.

Our findings presented in the research paper will hopefully have a direct value for the scientific community and contribute to a better understanding of adaptation to global warming. However, from a wider perspective, the results run a high risk of going largely unnoticed outside our immediate ‘science bubble.’ This is one of the reasons why I, over the past years, have increasingly focused on co-creation with artists to translate science into more approachable formats. At first glance, the scientific results are seldom at the center of our art. However, presenting the invisible, a snapshot from a seemingly outlandish world, may, in the best-case scenario, provoke lingering feelings that seek an explanation. Placing the actual artistic end result aside, we cherish the process where scientists and artists are equals and in which we merely function as intermediaries between human and nature. Making art out of science is an act of diversity, a type of lateral thinking that could be more widely practiced in decision-making in society in general. In this case, a collective memory from the seafloor is read by a camera in the installation Hidden Archives, simultaneously producing data for a soundscape. The sea has saved an evolutionary record for us to explore and composed a story for us to share.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Climate Change

A monthly journal dedicated to publishing the most significant and cutting-edge research on the nature, underlying causes or impacts of global climate change and its implications for the economy, policy and the world at large.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in