Goal-based water trading can lead to smarter investments for a more resilient future

Published in Sustainability

The urban water sector is under increasing pressure. Cities around the world are facing issues due to aging infrastructure, rapid urbanization, and intensified climatic variability. Today’s outdated water infrastructure was not designed to deal with these 21st century challenges. What is more, today’s water financing and governance models are not equipped to facilitate the updates needed fast enough to keep up with changing realities. Our Analysis paper in Nature Sustainability was inspired by the realization that infrastructure, governance, and financial systems are all not only part of the problem but also the essential part of the solution.

It turns out the solution has been right in front of our eyes for some time now, through examples from other sectors that have faced similarly complex and interdisciplinary challenges. In 1990, governments sought ways to address the problem of acid rain and reduce levels of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide that had accumulated since the industrial revolution. That year, the U.S. established the world’s first ever pollution trading system, popularized as “cap and trade.” The idea was simple, if radical: let people buy and sell the ‘right to pollute,’ while developing local market-based solutions as a way to clean up the environment.

The first “cap-and-trade” system worked. Not only did the market-based approach slash 36% of emissions in 14 years at a sixth of the cost – cleaner, faster and cheaper than anyone imagined possible. The regulatory skeleton of the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990 also spurred technological and contractual innovation at the local and regional level. Since 1990, many governments have successfully implemented “cap-and-trade” systems, not only to control acid rain, but also to limit carbon emissions and even to limit stormwater pollution discharges. These different applications have some common elements: regional caps or goals; limited credits; flexibility to develop local solutions; a credit banking option; an active monitoring system to inform the process and to enhance trust and transparency; and a penalty or fine that would guaranty action by all the beneficiaries. These are the elements we explored in our Analysis paper, in what we call a “goal-based water trading” approach.

Though some communities in drought-stricken regions have started piloting similar systems as a way to achieve water conservation at the customer level or a watershed scale, these schemes have yet to reach their full potential. The fact is that efforts to expand and diversify water supplies remain largely uncoordinated and erratic. What is missing is a structural shift that creates the right incentives and platforms for a broader group of actors to become engaged in the process. In the 1990 acid rain cap-and-trade example, the scheme allowed trading after two years, but significant emission reduction didn’t come until 1995 when the regulatory cap on emissions went into effect. Ironically, a voluntary market often requires a regulatory driver, and aside from water quality-based limitations on effluent, caps and targets have until recently been absent from the water sector, especially when it comes to supply quantity. But this is changing. California’s recent historic drought led Governor Brown to declare a state of emergency and introduce a rigid cap on water used by water agencies. Now the state has made restrictions permanent, requiring utilities to meet certain water use target by 2020. This type of regulatory vehicle presents a great opportunity for a goal-based trading model, especially for communities with a common pool of water resources such as a regional water system or a groundwater basin.

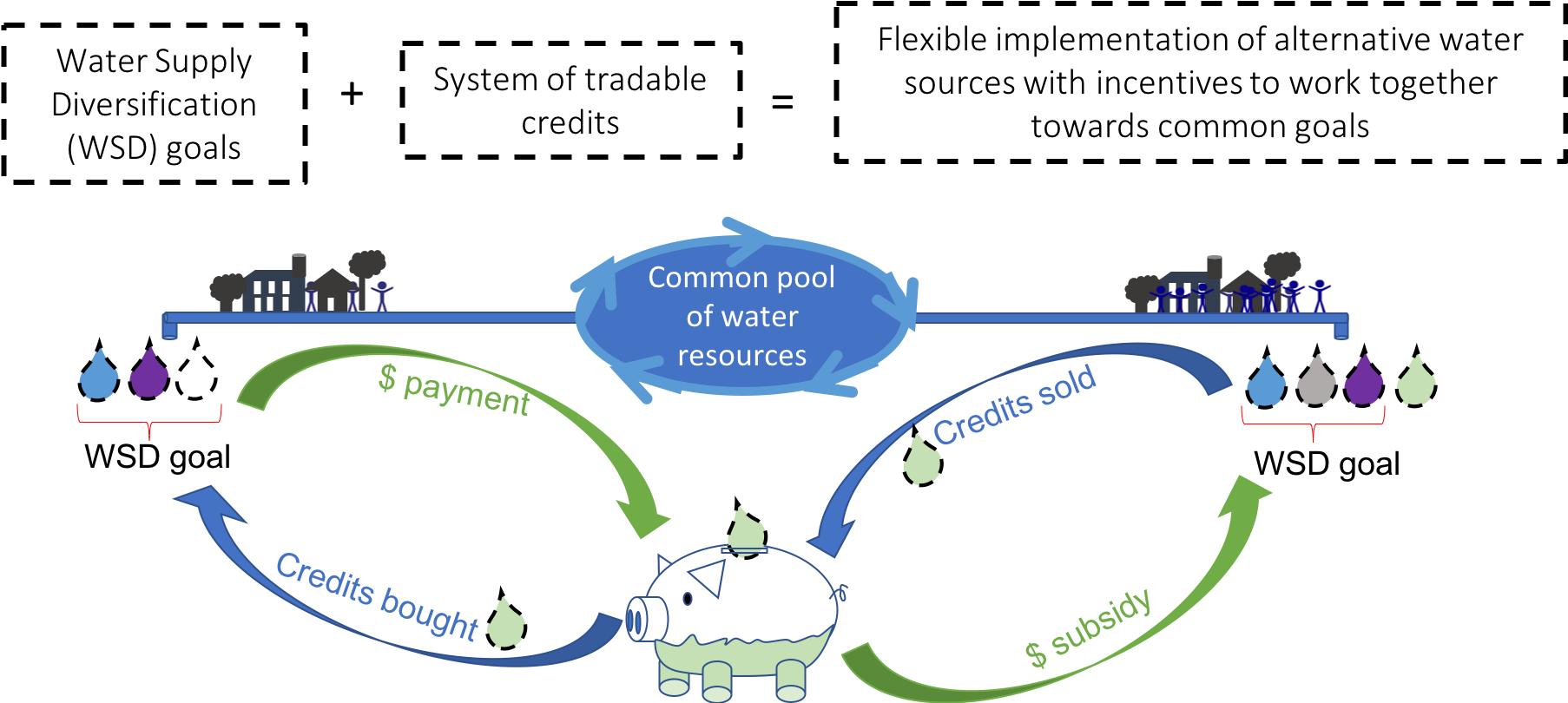

In our proposed goal-based water trading system, every drop of water a utility saves through efficiency measures or generated by alternative means (e.g. reuse, stormwater capture, gray water systems) will leave a drop of water in the common pool. That water unit saved then acts as a credit a utility can trade, to subsidize their investment costs or avoid fines. This market approach offers the flexibility for utilities to design and invest in water efficiency measures, or diversify their water supply portfolio, and meet their specific service area needs and capacity.

Our analysis shows that when a market is set in a transparent way, with a platform that enables various actors to cooperate and collaborate, regional goals can be met in the most economical and timely manner. These tools have the potential to attract investment from diverse stakeholders, speed the modernization of infrastructure, and drive a systematic approach that allows regional high-level goals to be achieved through bottom-up and holistic solutions.

Contributed by Patricia Gonzales and Newsha Ajami

Patricia Gonzales is an environmental engineer for Brown and Caldwell. She conducted this research as part of her PhD dissertation at Stanford University. She specializes in using data-driven insights along with economic, hydrologic, and governance perspectives to explore innovative environmental policies, support informed decision-making, and incentivize supply diversification for more reliable and resilient water systems.

Newsha K. Ajami is the director of Urban Water Policy with Stanford University’s Water in the West program and NSF’s ReNUWIt initiative. She is a leading expert in sustainable water resource management, water policy, innovation, and financing, and the water-energy-food nexus.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Sustainability

This journal publishes significant original research from a broad range of natural, social and engineering fields about sustainability, its policy dimensions and possible solutions.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in