If it takes so long to get there, why did the Neanderthals occupy Amalda?

Published in Ecology & Evolution

"I want to propose a project to you"

From this phrase, our adventure in Amalda began. This site has given rise to an extensive debate questioning the Neanderthal presence in relation to the role of carnivores, and hence about the nature of the accumulation of faunal remains. Amalda I was excavated by J. Altuna in the 1980s and this work allowed the recovery of a large number of lithic tools and fauna, which were analyzed, published, and inspired discussion. Our work at Amalda I started in 2016, when we planned the spatial study of the site, intending to conduct a deeper investigation into the controversy about the relationship between Neanderthal occupation and carnivore activity at this site, and if we could shed more light on it. The first step was to revisit the previously collected materials and data. We realized that many of the fauna and lithic remains were mixed, not cleaned, and therefore not studied.

Reviewing Amalda I materials at the Gordailu center.

After making this realization, we started processing the data and contacted colleagues who assisted with the analysis of faunal remains. At the same time, our minds were set on going to the field. In the summer of 2017, with a project funded by the Diputación Foral de Gipuzkoa, we went to Amalda I. The site is located in the Alzolaras valley, a communication point between the coastline and inner valleys. Accessing the cave is quite tricky due to the position of the cave in the karst and the features of the mountains and forests of the northern part of Spain. We discovered what happens when you do not have an appropriate vehicle in this difficult terrain… a wheel stuck in the mud.

Scarp where Amalda I is located.

The first obstacle is crossing a stream which, in frequently rainy Basque Country, is not easy to cross. Also, there is not bridge or any another option to traverse the stream without getting wet, so wearing rain boots or going barefoot are the best options. After crossing the stream, a long walk until a point with extremely low visibility marking the beginning of access path used in the 1980s to reach Amalda. This trail is barely marked, with very dense vegetation -a kind of jungle full of branches and brambles- and it is almost vertical; in many places climbing with our hands is necessary to continue ascending. After 40 minutes, we finally arrive to the cave. This is the daily routine if you want to excavate in Amalda I. It is difficult, but rewarding.

Descending from Amalda I...

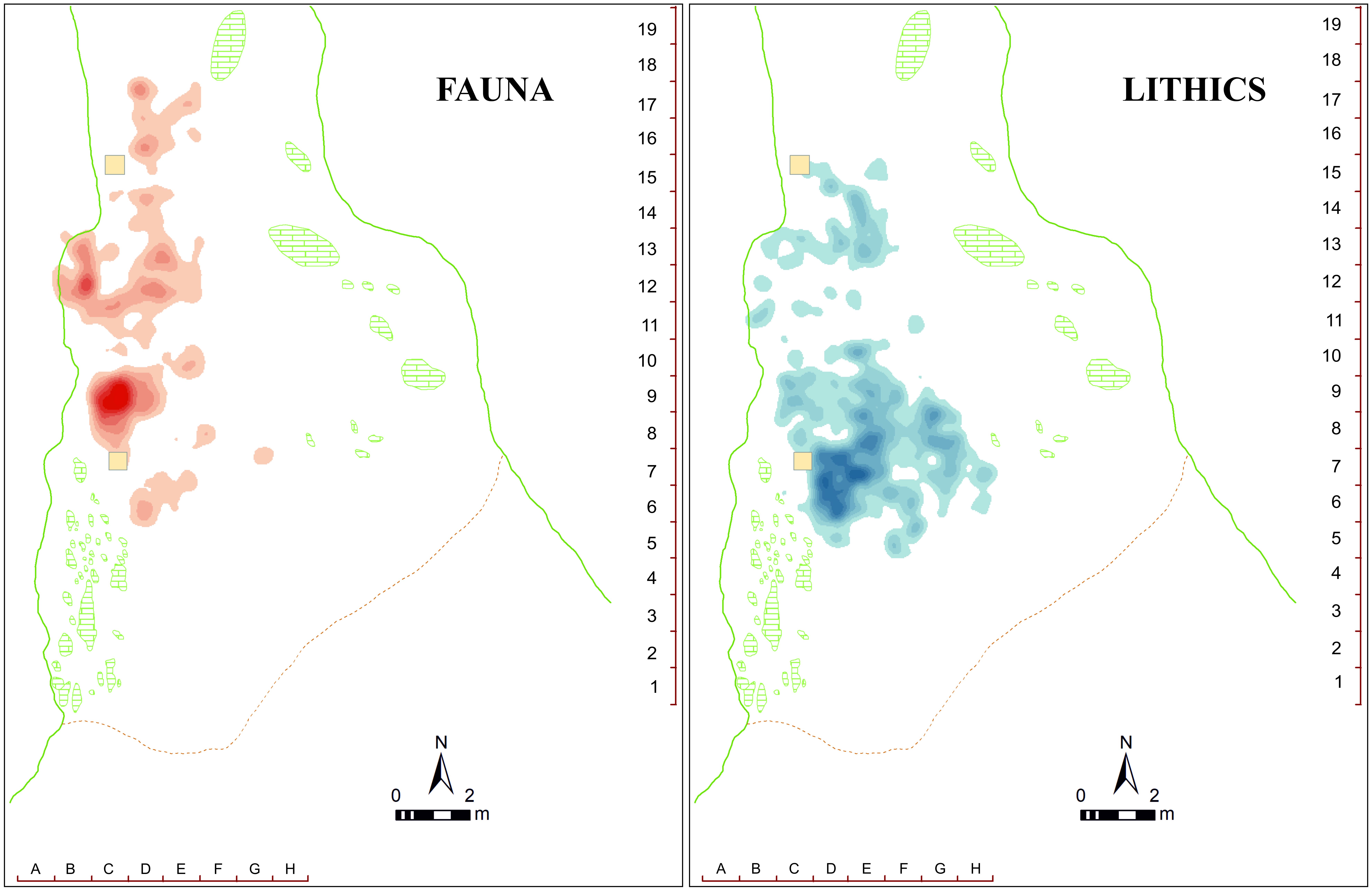

This study has allowed us to interpret the settlement and organizational patterns of Neanderthals, as well as the alternating occupation of the cave between humans and carnivores. This work has established that the major concentrations of lithics and medium-sized mammal remains were clearly accumulated by humans at the cave entrance, while the small mammals were gathered by carnivores in an inner zone. The activities of the Neanderthals seem to be distinctly structured, suggesting a parallel exploitation of resources.

Density plans of faunal and lithic assemblages of Amalda I.

The alternation in the occupation of the caves by carnivores and humans is present in other Palaeolithic sites. However, Amalda I is particularly interesting to assess the spatial organization of the activities and the use of space by Neanderthals, which has essential implications for understanding their social organization, such as the existence of well-structured productive processes, the division of labor or the existence of some kind of principles in the organization of the habitat. In the case of the carnivore activity, they may have accessed the remains left by humans, transporting them to inner and more protected zones, thus prompting another accumulation parallel to the one caused by humans.

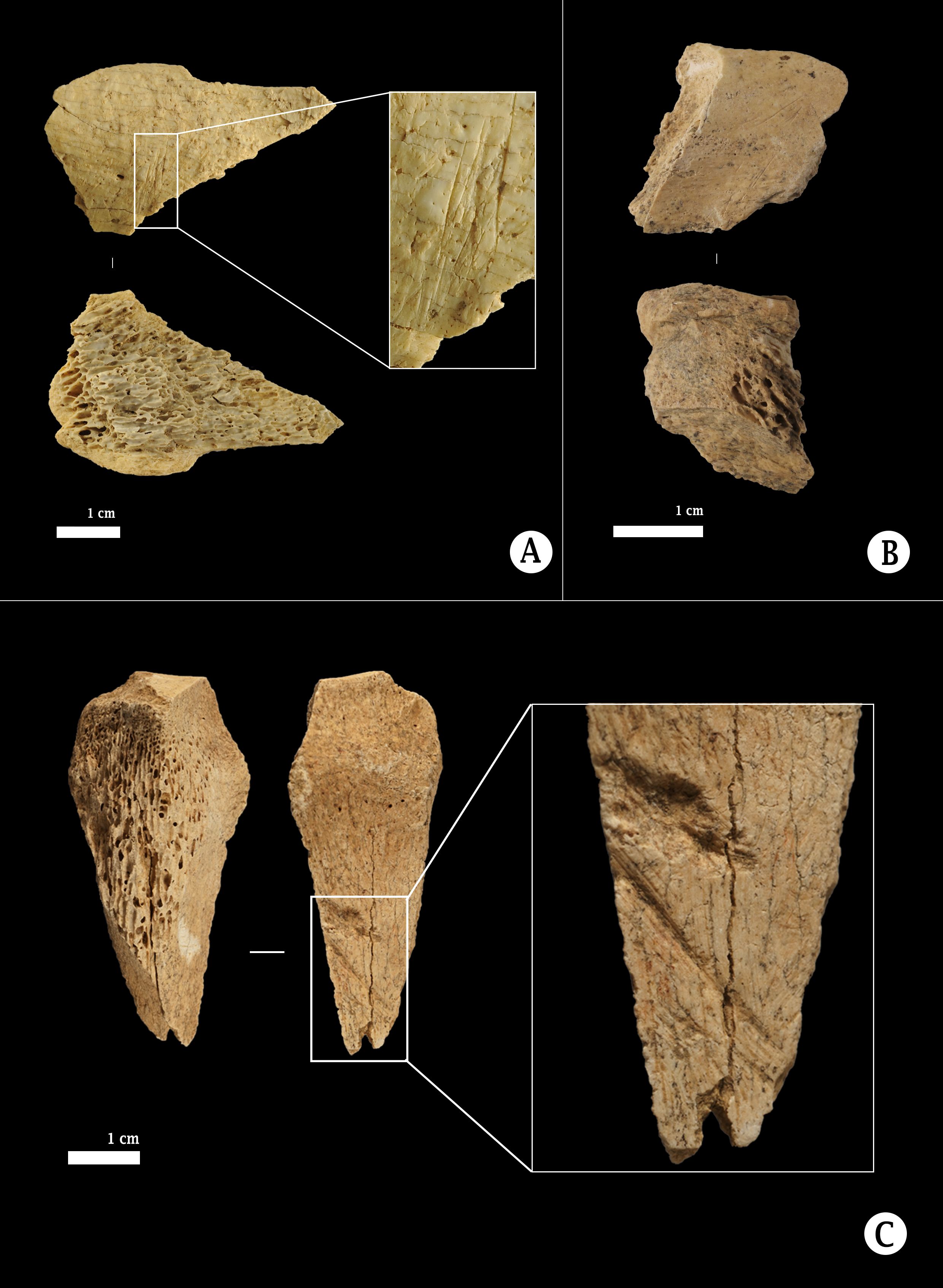

Anthropogenic modifications identified within faunal assemblage of Amalda I.

The result of all this effort, the combination of various professionals and, above all, the good harmony and friendship among the members of this team have allowed this work got ahead. Now, our eyes are on Amalda III, a small cave located in the same scarp, with evidence of human presence and with even more complicated access issues. After a walk of 40 minutes up the hill, we need to climb 30 meters of a vertical limestone wall to get to the entrance of the Amalda III cave. How did humans get there? And why did they keep going back? The adventure continues…

Photo of Amalda III captured by drone.

Part of the Amalda team.

Follow the Topic

-

Scientific Reports

An open access journal publishing original research from across all areas of the natural sciences, psychology, medicine and engineering.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Reproductive Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 30, 2026

Obesity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Apr 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in