Minibinders: Tiny Proteins with Huge Potential in Bioengineering

Published in Bioengineering & Biotechnology and Biomedical Research

Proteins vary greatly in size, from thousands of amino acids to fewer than 20. However, smaller proteins are not necessarily less important. Miniproteins, microproteins, or ‘minibinders’, typically under 100 amino acids, are gaining attention for their potential pharmaceutical applications. These minibinders occur naturally in various organisms - recent studies suggest that hundreds or even thousands may be expressed in different organisms (Aspden et al., 2014; Bazzini et al., 2014; Sberro et al., 2019). Historically, they were often overlooked because proteins with fewer than 100 amino acids were typically excluded from analyses (Leslie, 2019). However, these minibinders are highly diverse in function, often capable of regulating much larger proteins (Leslie, 2019). Moreover, they are more cost-effective to produce (as they can be expressed in bacteria) and highly stable (with melting temperatures exceeding 90º, allowing for room temperature storage).

A recent study by David Baker’s team highlighted the potential of minibinders by designing ones that could bind to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein with an affinity comparable to antibodies, yet at a fraction of the size (Cao et al., 2020). Their most promising minibinder (LCB1) is being tested as a prophylactic nasal spray to protect against SARS-CoV-2 infection. These results suggest a significant potential for using minibinders in therapeutic applications. Minibinders also play roles in tissue development and function, such as the Tal protein in Drosophila, which is essential for leg development (Pueyo & Couso, 2008), and myoregulin in mice, which regulates muscle contraction (Anderson et al., 2015).

Beyond their natural roles, synthetic minibinders are being explored as potential therapeutics. Their small size (1-10 kDa) and ability to bind targets with high specificity and affinity make them suitable for applications where small molecules or antibodies may not be effective (Crook et al., 2020). They are also easier to produce and administer than antibodies. Several synthetic minibinders are under development and serve different functions, including acting as agonists, antagonists, protein-protein interaction disruptors, 'ferries' for drug delivery, and 'joiners' to bring targets together (Crook et al., 2020).

Natural minibinders have inspired many pharmaceuticals. For example, chlorotoxin from the deathstalker scorpion specifically binds glioma brain tumor cells. A modified form of chlorotoxin (fusion with a fluorescent dye) has allowed for tumor visualization and removal (Deshane et al., 2003); this "Tumor Paint" is now in clinical trials (Leary et al., 2020). Entirely novel minibinders, not based on natural templates, are also being developed. The SARS-CoV-2-binding minibinders mentioned above are an example (Cao et al., 2020). They used two methods to generate high-affinity binders: one based on the ACE2 receptor helix and another from scratch. The latter method proved more successful, resulting in minibinders with sub-nanomolar affinity and potent virus neutralization (Cao et al., 2020).

Minibinders offer several advantages over antibodies. . Minibinders can exhibit high thermostability, allowing for room temperature storage and resilience to extreme conditions, which is particularly beneficial for distribution and storage in various environments. Additionally, they are more cost-effective to produce, as they can be expressed in bacteria, which simplifies the manufacturing process, or could be much more easily expressed following gene delivery protocols in vivo, e.g. skeletal muscle gene delivery. Their small size allows for better tissue and cell penetration, making them more effective in reaching their targets . Continued advances in protein engineering and computational methods, combined with the exploration of small proteins, could revolutionize pharmaceutical development.

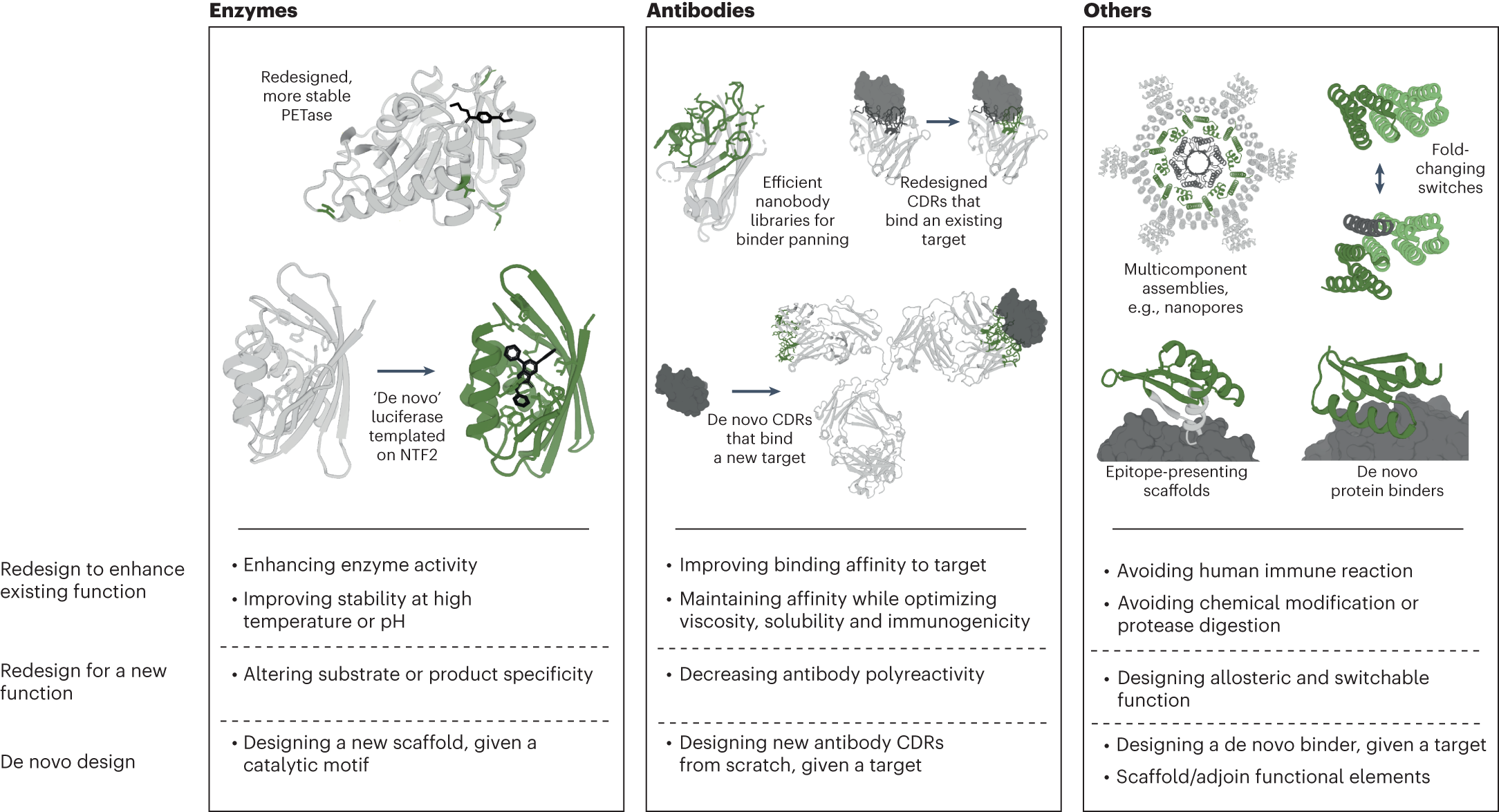

Protein Design Applications. Examples of machine learning-driven protein design applications for different protein types across the three protein design objective categories. NTF2, nuclear transport factor 2.

From Notin, P., Rollins, N., Gal, Y. et al. Machine learning for functional protein design. Nat Biotechnol 42, 216–228 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-024-02127-0, with permission.

Recent breakthroughs in AI coupled with the rapid accumulation of protein sequence and structure data have radically transformed computational protein design.

New methods promise to escape the constraints of natural and laboratory evolution, accelerating the generation of minibinders for applications in biotechnology and medicine (Notin et al., 2024). Machine learning models can predict the binding affinity and stability of designed minibinders, optimize their sequences, and even generate novel structures. This integration of computational tools and experimental validation is paving the way for the rapid development of effective minibinders for therapeutic use. Looking ahead, several directions hold promise for further advancing minibinder design. Scaling data and models can improve performance, with larger datasets of protein sequences enhancing generative models and design quality. The growing amount of data on protein functions allows for finer-grained control of design, enabling the generation of sequences tailored to specific functions and conditions. In silico evaluation using benchmarks like ProteinGym and FLIP helps guide model development, while experimental evaluation requires unbiased benchmarks for practical design tasks. Combining structure-aware and sequence-based models, along with protein language models, can enhance protein design. Integrating machine learning with biophysics principles and improved sampling approaches will increase the quality of generated sequences, accelerating end-to-end design cycles, and leading to models capable of supporting efficient design iterations and de novo tasks.

In conclusion, minibinders are small but incredibly promising new players in the field of bioengineering, with immense potential for therapeutic applications. As research and technology continue to advance, we can expect to see even more innovative uses for these tiny yet powerful proteins.

References:

-

Cao et al., 2020: Cao, L., Goreshnik, I., Coventry, B., Case, J.B., Miller, L., Kozodoy, L., Chen, R.E., Carter, L., Walls, A.C., Park, Y.J., Strauch, E.M., Stewart, L., Diamond, M.S., Veesler, D., & Baker, D. (2020). De novo design of picomolar SARS-CoV-2 miniprotein inhibitors. Science, 370(6515), 426-431.

-

Leslie, 2019: Leslie, M. (2019). The tiny proteins that pack a big punch. Science, 365(6452), 1086-1089.

-

Aspden et al., 2014: Aspden, J.L., Eyre-Walker, Y.C., Phillips, R.J., Amin, U., Mumtaz, M.A.S., Brocard, M., & Couso, J.P. (2014). Extensive translation of small Open Reading Frames revealed by Poly-Ribo-Seq. eLife, 3, e03528.

-

Bazzini et al., 2014: Bazzini, A.A., Johnstone, T.G., Christiano, R., Mackowiak, S.D., Obermayer, B., Fleming, E.S., Vejnar, C.E., Lee, M.T., Rajewsky, N., Walther, T.C., & Giraldez, A.J. (2014). Identification of small ORFs in vertebrates using ribosome footprinting and evolutionary conservation. The EMBO Journal, 33(9), 981-993.

-

Sberro et al., 2019: Sberro, H., Fremin, B.J., Zlitni, S., Edfors, F., Greenfield, N., Snyder, M.P., Pavlopoulos, G.A., Kyrpides, N.C., & Bhatt, A.S. (2019). Large-scale analyses of human microbiomes reveal thousands of small, novel genes. Cell, 178(5), 1245-1259.e14.

-

Pueyo & Couso, 2008: Pueyo, J.I., & Couso, J.P. (2008). Tarsal-less peptides control Notch signalling through direct interaction with the Notch receptor. Nature Communications, 1, 1-8.

-

Anderson et al., 2015: Anderson, D.M., Anderson, K.M., Chang, C.L., Makarewich, C.A., Nelson, B.R., McAnally, J.R., Kasaragod, P., Shelton, J.M., Liou, J., Bassel-Duby, R., & Olson, E.N. (2015). A micropeptide encoded by a putative long noncoding RNA regulates muscle performance. Cell, 160(4), 595-606.

-

Crook et al., 2020: Crook, Z.R., Nairn, N.W., & Olson, J.M. (2020). Miniproteins as novel therapeutics. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology, 56, 179-185.

-

Deshane et al., 2003: Deshane, J., Garner, C.C., & Sontheimer, H. (2003). Chlorotoxin inhibits glioma cell invasion via matrix metalloproteinase-2. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 278(6), 4135-4144.

-

Notin et al., 2024: Notin, P., Rollins, N., Gal, Y., Sander, C., & Marks, D. (2024). Machine learning for functional protein design. Nature Biotechnology, 42(2), 216-228.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in