Remarkable mate guarding behavior of the small water strider, Microvelia iriomotensis (Heteroptera: Veliidae)

Published in Ecology & Evolution

Precopulatory mate guarding behavior is a common strategy among males of many insect species. Mate guarding increases the probability of mating with females; however, it is costly for males, in terms of predation risk, food deprivation, and energy costs. In Veliidae (Insecta: Heteroptera), reports of males mate guarding of immature females, especially at the nymphal stage, are rare, with this behavior reported only in three species. In 1953, a Microvelia leveillei (Leithierry) male mounted a female nymph; however, copulation was unsuccessful because of the predation of the female nymph by other adults. The sex ratio of adult Phoreticovelia rotunda Polhemus et Polhemus and P. disparata Polhemus et Polhemus (Heteroptera: Veliidae) was markedly male-biased, with males that failed to mount female adults mounting fourth- and fifth-instar female nymphs. These behaviors may increase male mating success, and females may spend long periods of time carrying male adults on their backs. These three species have pronounced sexual dimorphism; therefore, male mate guarding of nymphal females could be restricted to species with developed sexual dimorphism, where the sex ratio is male-biased and/or females are larger. Our discovery would alter this prevailing knowledge. Pre-copulatory mate guarding behavior was observed in Microvelia iriomotensis, which had small differences in body size and unbiased sex ratios. We raised more than 500 eggs and observed them closely to confirm that this behavior was not accidental.

Which stage of female does the male choose to mate with?

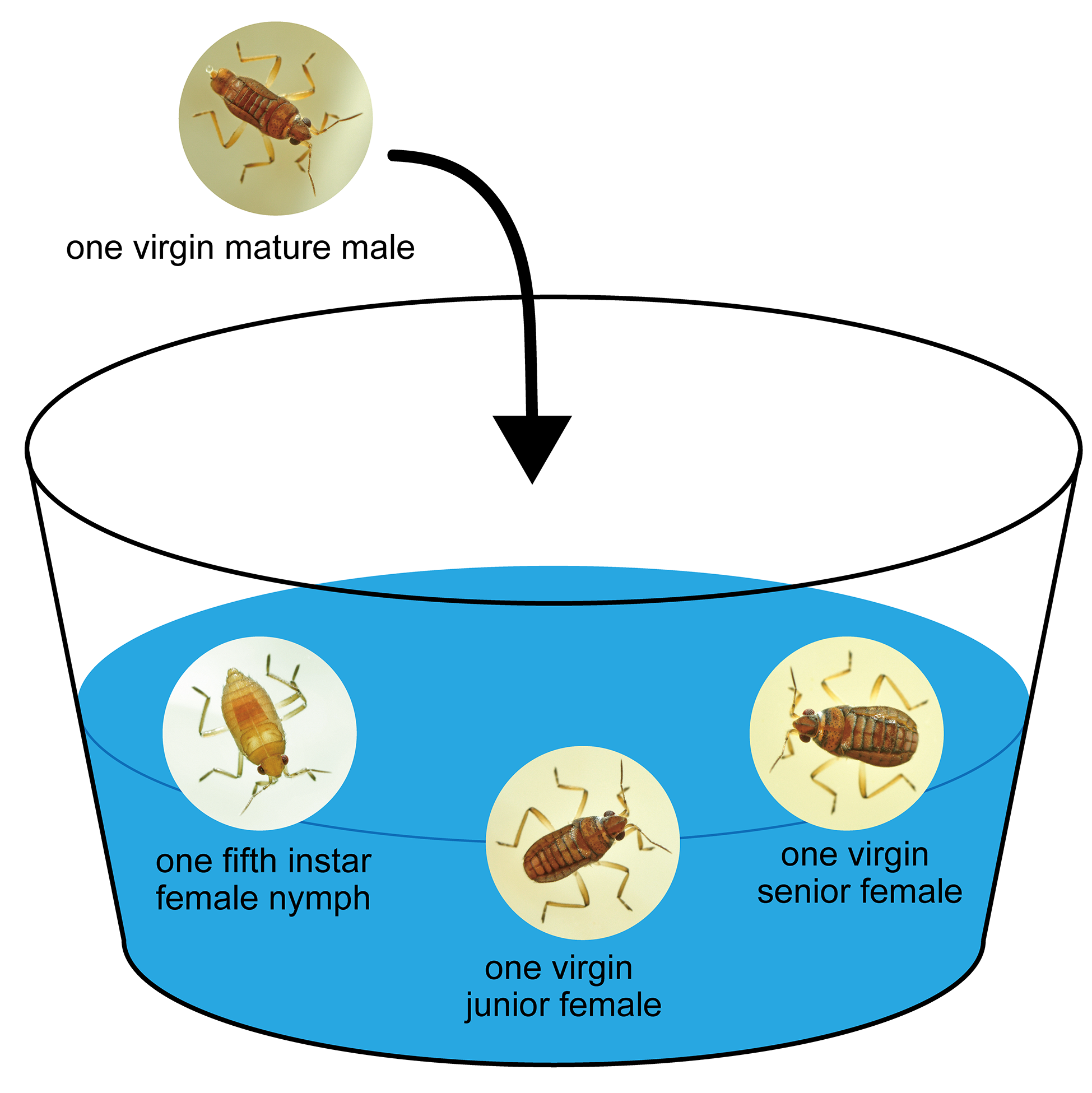

To determine which life-stage females the males preferred as their mating partners, females at three life stages–one virgin female more than three days after emergence (hereinafter referred to as a senior female), one virgin female within 24 h of emergence (hereinafter referred to as a junior female), and one fifth-instar female nymph–were placed in a clear plastic cup.

Males tended to approach senior females first. The first males to be mounted were biased toward more senior females, and this trend was consistent with the female that was eventually mated. There was only one case in which a male mounted a female nymph. In this case, the emerging adult female quickly moved forward and away from the male, while the male continued to mount on the exuvium of the female for 1140.03 min (approximately 19 h).

To examine whether males mounted female nymphs in the absence of adult females, we conducted the following experiment: one mature virgin male and one fifth-instar female nymph were placed in a rearing cup; 79.6% of males mounted the female nymphs within 5 h, and all males were observed to chase the female nymphs, including those they did not mount. When female nymphs emerged, the males transferred to the emerged female and mated.

Number of eggs laid and period to first oviposition by junior and senior females

Seventy-five percent of adult females laid viable eggs within 24 h of emergence. There was no significant difference in the number of fertilized eggs or the number of eggs laid by the junior and senior females.

Confirmation of sex ratio

To determine the sex ratio, 226 eggs were hatched and the hatched individuals were raised to adulthood. The in vitro sex ratio was male: female = 1.09:1.00.

Conclusion

Senior females are the most preferred mating partners for males. Precopulatory mate guarding behavior can occur in species without sex ratio bias and with small differences in body size between males and females, such as Microvelia iriomotensis. The behavior of M. iriomotensis males mounting nymphs could be related to the early receptivity of females to mating, which allows them to lay fertilized eggs soon after emergence. Males mounted on nymphs were at a risk of requiring a longer time and sometimes failure to mate. However, there must be reasons why many males start the precopulatory mate guarding when the female is a nymph. Further research is required to clarify this, particularly in the context of competition between males for females.

Follow the Topic

-

Journal of Insect Behavior

This Journal is a forum for publication of studies of insects and related Arthropod groups on orientation, migration, social behavior, sexual selection, rhythmicity, mate finding and courtship, learning, predation, defense, and host finding.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in