What if we could detect the tiniest of changes in RNA—one base out of thousands—without complex instruments, enzymes, or bulky sequencing machines? This question was at the heart of our study, now published in Nature Nanotechnology, where we introduce RNA-SCAN: a nanopore-based sensing platform that uses “nanolatches” to reveal single-nucleotide mutations and modifications in RNA.

Where It All Began

The idea was born from frustration. As researchers working with RNA, we are well aware of how crucial it is in both health and disease. A single nucleotide change can affect antibiotic resistance, viral virulence, or even tumor progression. Yet the tools we had—sequencing, chromatography, or structure-specific probes—often required amplification, complex chemistry, or high sample input.

Meanwhile, our lab had been working with solid-state nanopores, tiny holes that detect single molecules by the way they block electrical current as they pass through. The challenge? RNA is flexible and noisy. A small mutation or modification barely causes a ripple in the signal.

Could we engineer something to make those ripples louder?

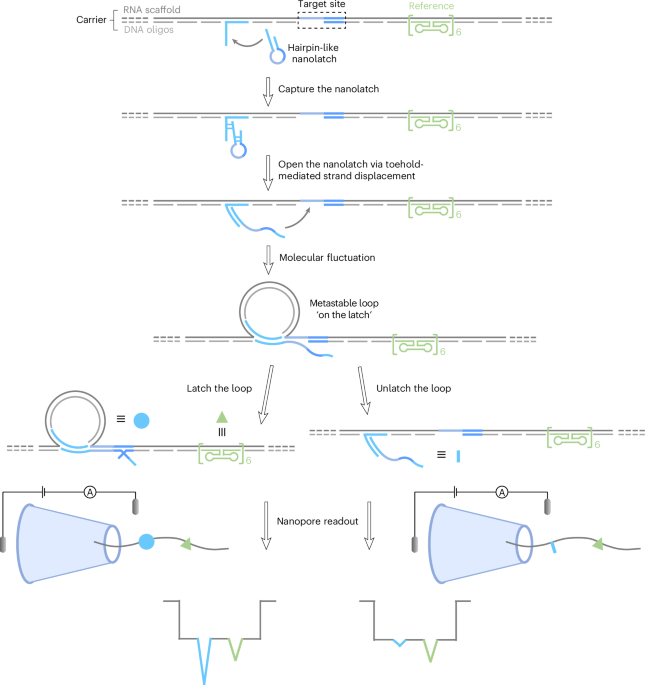

Designing the Nanolatch

Our breakthrough came with a clever concept: what if we added a DNA-based “molecular switch” that would only latch onto a specific RNA sequence and only if it matched perfectly? This “nanolatch” forms a loop structure when the sequence is correct, generating a clear spike in the nanopore current. A mismatch or chemical modification weakens the interaction, breaking the loop and causing the spike to disappear.

This design gave us a binary, yes-or-no signal for detecting single-base changes—without needing enzymes or labels.

But the road to a working nanolatch was far from simple. Getting the latch to fold, unfold, and find the right site in real time meant wrestling with molecular design rules, thermodynamics, and lots of gel electrophoresis. We had to create RNA/DNA hybrid “carriers” that expose specific regions of RNA while remaining stable enough to thread through a nanopore.

The final design—using a 10-nucleotide pairing region and an 8-nucleotide “competitive” overhang—allowed us to tune the binding strength and maximize detection sensitivity.

Proof of Concept, with Bacteria and Viruses

To demonstrate the platform, we started with viral RNA from bacteriophage MS2, where we could control single-nucleotide substitutions in corresponding nanolatches. They clearly differentiated between perfect matches and point mutations.

Then came a real-world challenge: detecting the difference between E. coli and Salmonella Typhi based on a single nucleotide in their 16S rRNA. Despite over 97% sequence similarity, RNA-SCAN reliably distinguished the two species with signal differences over 10-fold.

We also showed that the method could detect RNA modifications such as 5-methylcytosine and inosine, which are key to epigenetics and RNA editing. A single 5-methylcytosine increased the signal. A single inosine nearly abolished it. The signal strength correlated neatly with modification number and thermodynamic predictions, an inspiring moment of harmony between theory and experiment.

Perhaps most exciting was our application to real clinical samples. By using total RNA directly from bacteria, skipping both amplification and purification, we were able to quantify mixtures of different Salmonella subspecies and detect naturally occurring 5-methylcytosine in E. coli, using A. baumannii as an unmethylated control.

What Comes Next

RNA-SCAN is not a sequencing technology, but a precision sensor. It doesn’t give you the whole transcriptome, but it tells you exactly whether a specific change or modification is present. This makes it ideal for applications like rapid bacterial identification, antibiotic resistance profiling, and epitranscriptomic screening.

Looking ahead, we hope to scale up the system for higher-throughput detection. By combining multiple nanopores and barcoded nanolatches, we envision a “lab-on-a-chip” platform that could screen dozens of targets simultaneously.

We also believe the design principle of combining programmable nanostructures with nanopore sensing can go far beyond RNA. Imagine detecting proteins, small molecules, or even RNA-RNA interactions using similar dynamic loops.

A New Way to Interrogate Molecules

Ultimately, what excites us most is not just what RNA-SCAN can do today, but the new conceptual space it opens up. By turning molecular binding into a digital signal, we’ve created a platform that is as elegant as it is practical, merging synthetic biology, biophysics and nanotechnology in a way that’s intuitive, tunable, and ready for real-world use.

We hope this work inspires others to think differently about how we detect and understand biomolecules, one latch at a time.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Nanotechnology

An interdisciplinary journal that publishes papers of the highest quality and significance in all areas of nanoscience and nanotechnology.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in