‘O salty sea, so much of whose salt

Is Portugal’s tears!’

- Fernando Pessoa

We love tasty food; we are sure we are not alone in that. We are also sure that tasty does not always mean healthy. But perhaps, our desire for tasty – or actually salty – food is a fundamental trait of all human beings, engraved so long ago in our DNA that we forget how the early forms of lives thrived in the salty ocean waters. Our pursuit of salt, now commonly accepted (and scientifically proved) as something 'unhealthy', represents not only a physiological need but, more deeply, a remote memory of the taste of the sea.

Figure 1. The historical town of Macau inspires poets, artists and perhaps scientists from now on (photo credit C Wang).

As we chew over Pessoa’s poem in Macau and salted duck in Nanjing, which can be connected by salt, we remind ourselves that salt has become, and still is, one of the essential inorganic substances for all lives on the planet. Multicellular organisms, coincidentally including the readers and authors, have enveloped the ‘ancient seawater’ in their body (if not in the memory). Na+and Cl-in the cytoplasm and body fluids silently collaborate to balance the osmotic pressure in the membrane system, keep the proper structures of protein molecules, drive key processes via the elaborately controlled ion gradients across the membrane. For so many centuries, as part of the evolution of terrestrial animals, we human beings were chasing salt - pure, white, glossy salt - so avidly as we did for gold; today, how can we blame our greediness for salty food? Salt is more precious than gold, both physiologically and emotionally, as it is indispensable for both the rich and poor to survive the terrestrial environment. Only since technology has unlocked the limitation for salt production, the over-salty diet has become a health problem.

In a cold rainy night, sitting around a table in a small restaurant in Nanjing, some of the leading authors of this paper (High-salt diet inhibits tumour growth in mice via regulating myeloid-derived suppressor cell differentiation) were arguing about the problems of high-salt foods while taking the delicious salted duck, a typical Nanjing cuisine with a proud 500-year tradition. These trained biologists were undoubtedly aware that high salt intake increases blood pressure, damages circulation system, and elevates the osmotic pressure in the immune cells to trigger inflammation. Almost at the same time, they asked themselves – does the increased immune activity benefit in some conditions, such as in the treatment of cancer? Many cancers develop through silencing immune responses. So, instead of ‘adding salt in a wound’, what if spreading a pinch of salt in a tumour?

Figure 2. Leading authors brainstormed at a dinner in Nanjing (From right: C Wang, L Dong and Y Zhu [who sponsored the dinner]. The photo was purposelessly shot by the first author of the paper, Dr W He).

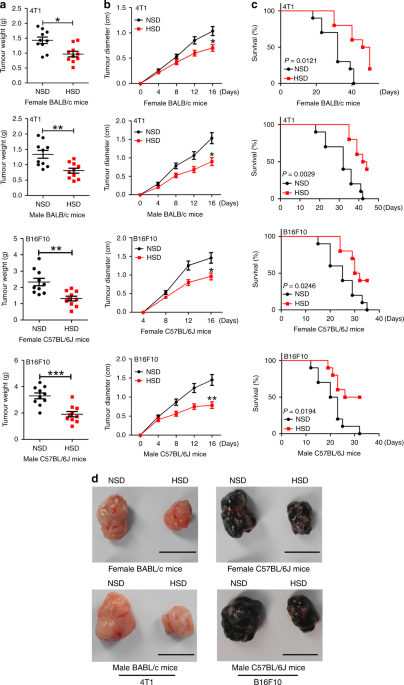

The next day, Dr Wei He, the first author of the paper, started to plan for his first exciting experiment – setting tumour-bearing mice on a high-salt diet. When the outcomes came out, his was so much encouraged that I cannot accurately describe it here but would passionately invite you to read our paper. Salt – the most basic stuff in our kitchen and a public enemy of health – demonstrated its unprecedented potential of fighting against the most notorious killer of life.

Figure 3. Salted duck, a typical Nanjing cuisine, with a 500-year tradition as proud as the history of this ancient capital city (photo credit L Dong).

Following the basic biological principles in cancer immunology, we eventually clarified the mechanisms underlying salt suppressing tumour growth. MDSC, an important group of immunosuppressive cells, significantly expand during tumourigenesis; but their functions drastically curbed by salt. Elevated osmotic pressure in tumor tissue – another exciting finding that dietary salt preferentially accumulates in the tumor – switches the immunosuppressive MDSC into pro-inflammatory cells with tumouricidal capability.

Na and Cl, two elements born along with the Sun in a supernova billions of years ago, dissolved in the ancient seawater and magically initiated the life on this planet. Now, without the accompany of Tequila and lemon, salt is whispering in our ears of her another magic power: 'Would someone like a pinch of me in a tumour?'

- Lei Dong, PhD, Professor at Nanjing University

- Chunming Wang, PhD, Associate Professor at University of Macau

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in