Temperature extremes exacerbate energy insecurity – Australia needs to better support remote Indigenous communities to prepare now

Published in Sustainability

Werte (hello/welcome).

This blogpost tells the story behind our paper Energy insecurity during temperature extremes in remote Australia, published in Nature Energy this month.

Co-workers and I at Tangentyere Council Research Hub started investigating the relationship between temperature, electricity use and involuntary self-disconnection in 2018. Extreme heat is a big issue, and the number of extreme temperature days in 2018/19 surpassed even the most severe projections of what we could expect under future climate change scenarios. It concerned our team greatly. Aboriginal social housing residents from Mpwartne/Alice Springs, its Town Camps and remote Central Australia were also reporting frequent disconnection from prepaid residential energy services and concerns about the amount of money spent to power their homes.

With the cooperation of our local utility, our preliminary investigation of 426 households prepaying for electricity in Town Camp housing revealed that 91 per cent of homes were disconnected from electricity during 2019–20 and many homes had multiple disconnections. Broadening our scope to all major regional centers, we found that in the larger Northern Territory (NT) towns of Darwin, Alice Springs, Katherine, and Tennant Creek, 71% or 1467 (of 2074) households experienced at least one involuntary self-disconnection from electricity in the three months between April and June 2020. The average duration that homes were losing power was almost 5 hours. The average number of disconnections for this period was nearly 9 per household per quarter.

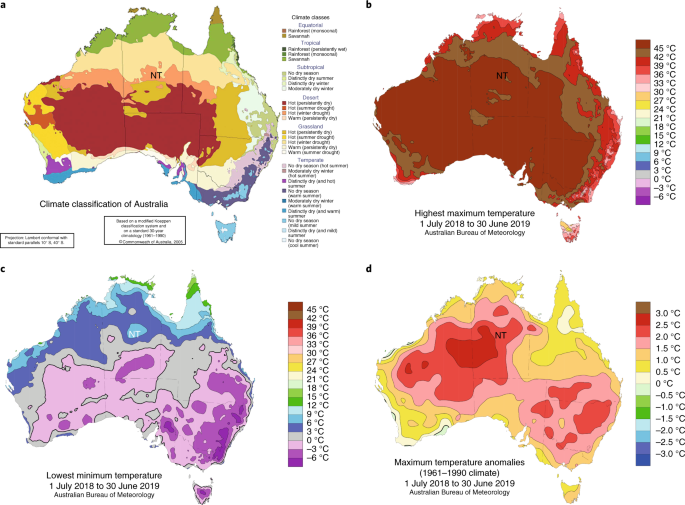

Predicting that a similar situation likely existed in NT remote communities, and supported by data from the utility, we undertook a study with colleagues from Julalikari Council Aboriginal Corporation in Tennant Creek and the Australian National University, to analyze daily electricity use data for 3,300 households matched to temperature data from the nearest weather station. While perhaps unsurprisingly temperature extremes were found to impact energy use, they were also found to increase the risk of remote living residents being disconnected from prepaid energy services in 28 remote Indigenous communities.

Confirming the relationship between temperature, electricity use and disconnection we demonstrate that 49,000 (29% of 170,226) incidences of involuntary self -disconnection occurred during hot and cold temperature extremes. 71% of households experienced a same-day disconnection more than 10 times in a twelve-month period - a rate much higher than other Australian and international examples – while climate zones in the Territory also influence the probability of a same-day disconnection occurring. For those households with the highest electricity use in the two southern climate zones, an already high 1-in-7 chance of experiencing a same-day disconnection on moderate (20ºC and 25ºC) temperature days increased to 1 in 3 for the coldest temperatures (0ºC to 15ºC) and 1 in 4 for the hottest temperatures (30ºC to 40ºC).

While energy insecurity describes more than disconnection rates alone - socio-economic, demographic and behavioral factors, occupancy and structural characteristics are all key drivers of energy consumption - and the level of energy service viewed as ‘essential’ can vary over time and with changing social norms, a complete loss of access to energy services constitutes a level of energy insecurity that can harm wellbeing.

Wellbeing concerns are particularly paramount for elders in our community, those with chronic co-morbidities and young babies. Disconnections can precipitate households needing to replace food and medicines that have spoilt in the heat. It is not uncommon for residents on lower incomes to face challenging trade-offs - between paying for electricity to maintain thermal safety or paying for food and other necessities.

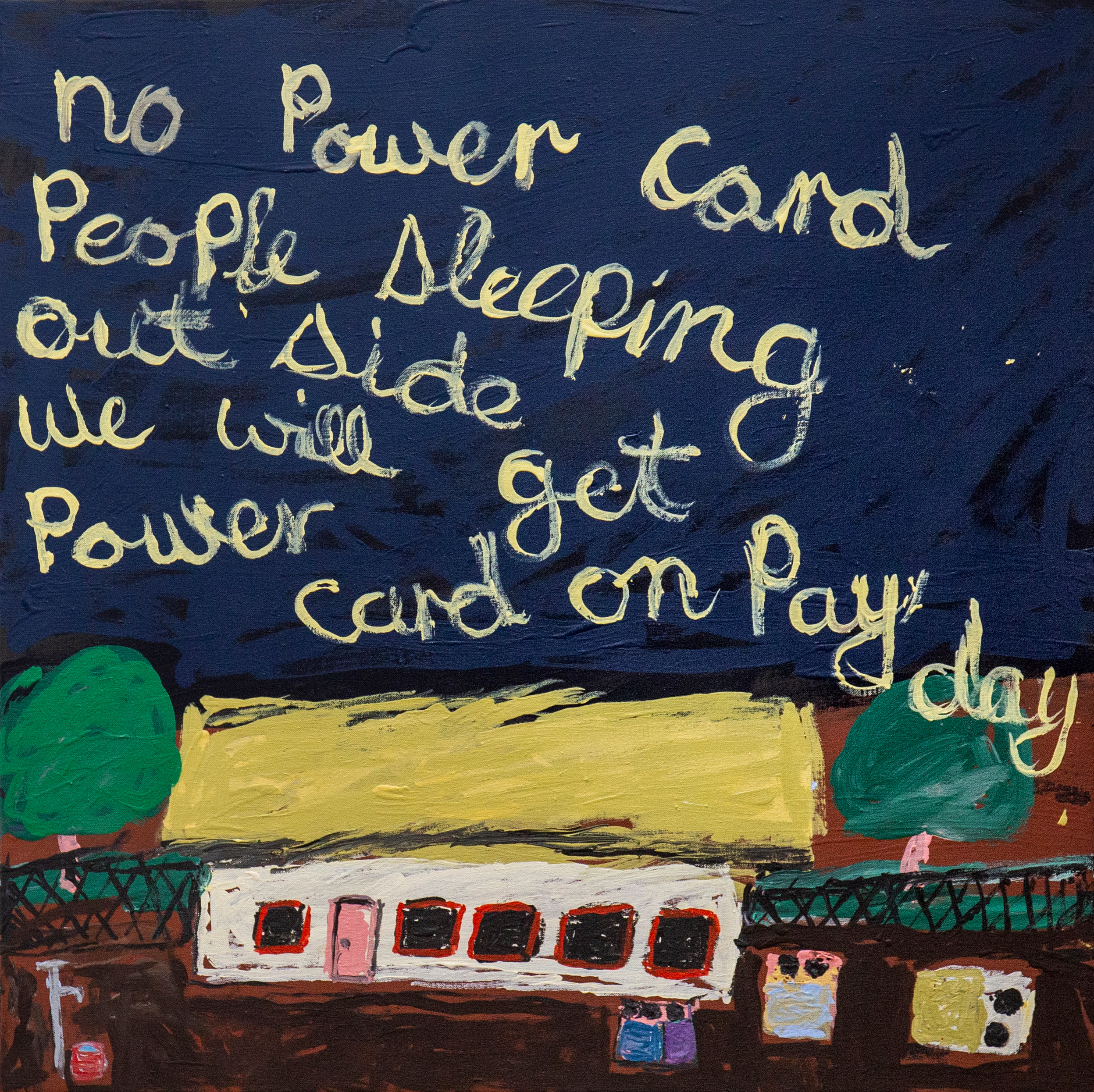

Disconnection quickly renders housing inadequate during temperature extremes and without access to electricity, many residents choose to sleep outside, as shown in the painting above by Central Australian artist Sally Mulda.

As my co-author Norman Frank Jupurrurla, a respected Warumungu elder from Tennant Creek explains;

“When the power disconnects because we run out of money, you have to hurry up. If you catch it in a few hours, you'll be lucky, otherwise everything goes off in the refrigerator. Then you have to throw everything out. Over recent summers it's been too hot - we have to get out of the house”.

Most Australians take reliable uninterrupted access to electricity for granted. But Australia could do much better at providing protections from disconnection for remote and regional First Nations communities.

Australian governments have agreed to ‘Closing the Gap’ in Indigenous disadvantage in partnership with First Nations. Evidence based policy responses built on foundations of transparent monitoring and reporting of disconnection data, and greater sharing of, and access to, data and information at a regional level with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-controlled organisations will be crucial. This data provides a comprehensive picture of energy insecurity in remote communities and can be used to help design solutions to reducing the frequency, duration, and negative impacts of disconnection from energy services for remote Indigenous residents.

Kele (Finish)

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Energy

Publishing monthly, this journal is dedicated to exploring all aspects of this on-going discussion, from the generation and storage of energy, to its distribution and management, the needs and demands of the different actors, and the impacts that energy technologies and policies have on societies.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Microgrids and Distributed Energy Systems

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in