The First Glimpse of “Resting-State” Activity in the Human Spinal Cord

Published in Neuroscience and General & Internal Medicine

For decades, scientists studying the brain have known that even when we’re doing nothing—just lying still with our eyes closed—our brains are far from silent. Networks of brain regions continue to “talk” to each other through subtle, rhythmic fluctuations in activity. These coordinated patterns, known as resting-state networks (RSNs), have reshaped our understanding of how the brain organizes itself and have even helped in diagnosing neurological and psychiatric disorders.

But what about the spinal cord—the long, slender bundle of nerves that runs down your back and connects your brain to the rest of your body? Until 2009, nobody had successfully shown that similar spontaneous, organized activity exists in the human spinal cord during rest. That changed with a pioneering study by Pengxu Wei and colleagues, titled “Resting State Networks in Human Cervical Spinal Cord Observed with fMRI.” This work marked the first time researchers demonstrated that the spinal cord, like the brain, exhibits intrinsic, low-frequency rhythmic activity when we’re at rest.

Why This Matters

Imagine your spinal cord as a kind of “information superhighway”: it carries movement commands from the brain to your muscles and sensory signals (like touch or pain) back up to the brain. But it’s not just a passive cable—it also contains its own local circuits that can process information and even generate rhythmic movements (like walking or breathing) on their own.

If we could observe how these circuits behave when we’re not actively moving or sensing anything, we might uncover new ways to understand—and potentially treat—conditions like spinal cord injury, chronic pain, or breathing disorders. That’s exactly what Wei’s team set out to explore using functional MRI (fMRI), a non-invasive imaging technique that detects blood flow changes linked to neural activity.

The Technical Challenge

Studying the spinal cord with fMRI is extremely hard. It’s tiny (only about 1 cm wide), surrounded by bone and fluid, and constantly jostled by breathing and heartbeat. Compared to the brain, which is large and relatively stable inside the skull, the spinal cord is like trying to photograph a wriggling earthworm in a storm.

To tackle this, the researchers scanned 10 healthy young men in a 1.5 Tesla MRI machine. They focused on the cervical (neck) region of the spinal cord—from vertebrae C5 to T1—which controls muscles in the arms, shoulders, and breathing. Each participant underwent two 6-minute “resting-state” scans, during which they simply lay still with their eyes closed.

A Clever Analysis Strategy

Because there was (and still is) no standard anatomical template for aligning spinal cord data across people—as exists for the brain—the team couldn’t do group-level statistics. Instead, they used a within-subject reproducibility approach: for each person, they compared the two separate resting scans to see if similar patterns appeared both times.

They analyzed the data using Independent Component Analysis (ICA), a method that separates mixed signals into their likely sources—like untangling overlapping voices in a crowded room. This allowed them to isolate true neural-related signals from noise caused by motion or blood flow.

Importantly, they applied a two-step motion correction process and manually outlined the spinal cord in each scan to avoid contamination from surrounding tissues. They also filtered out components that looked like artifacts—such as signals only at the edge of the cord (a sign of motion) or those with implausibly large signal changes.

What They Found

Across the eight usable participants (two were excluded due to excessive motion), the team found consistent spatial patterns of spontaneous BOLD (blood oxygen level–dependent) signal fluctuations between the two sessions. The correlation values ranged from 0.18 to 0.44—modest but statistically significant and comparable to early brain resting-state studies.

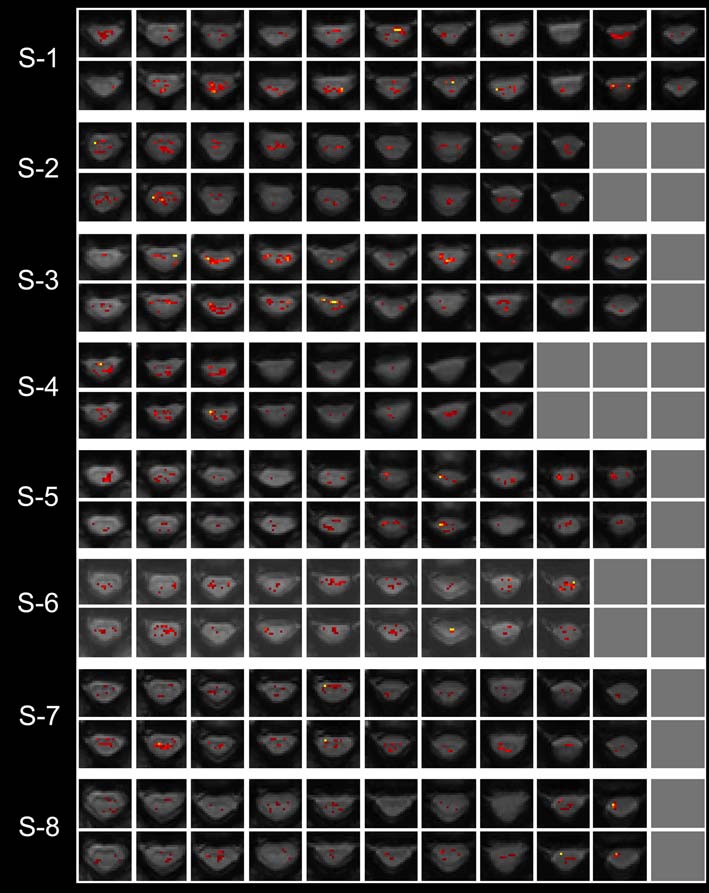

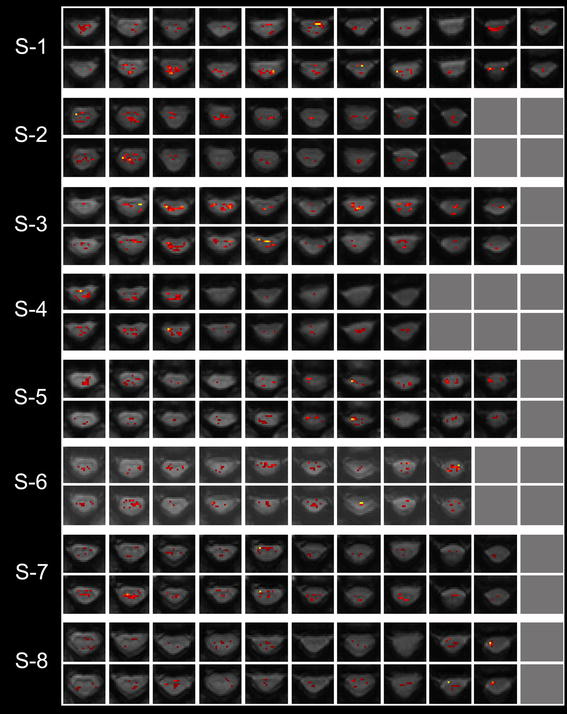

Figure 1 from the paper displays these matched component maps for each subject, slice by slice, showing similar activation patterns across sessions—especially in the ventral (front) regions of the cord.

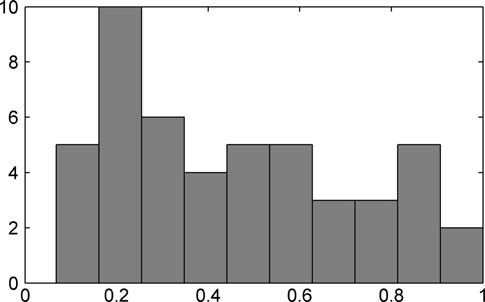

Even more revealing was the frequency analysis. The dominant rhythm of these fluctuations was around 0.27–0.33 Hz, which corresponds exactly to the normal human resting breathing rate (16–20 breaths per minute).

This led the authors to a compelling hypothesis: the observed signal likely reflects the rhythmic firing of spinal motor neurons that control the scalene muscles—a group of neck muscles critical for quiet breathing. These neurons live in spinal segments C5–C8, precisely the region scanned in this study.

Figure 2 (a histogram of power spectrum peaks) would illustrate how most signal energy clusters tightly in the respiratory frequency band.

Interestingly, some signal changes also appeared outside the ventral horns (where motor neurons reside), suggesting other types of neurons—perhaps interneurons involved in coordination or modulation—might also be part of this resting network.

Why Breathing? And Why It’s Important

At first glance, it might seem underwhelming that the “resting-state network” in the spinal cord is just about breathing. But that’s actually profound. Breathing is automatic, rhythmic, and essential—and it continues without conscious effort. The fact that fMRI can detect this underlying rhythm non-invasively opens the door to studying how spinal-level control of respiration might change in disease.

For example, in conditions like ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease), spinal motor neurons degenerate, leading to breathing difficulties. Could resting-state spinal fMRI one day help track disease progression or response to therapy? The authors suggest this is a real possibility.

A Foundational Study

While limited by the technology of its time (1.5T MRI, no group template, small sample), this 2009 paper was trailblazing. It proved that:

- Spontaneous, reproducible BOLD fluctuations do exist in the human spinal cord at rest.

- These signals are physiologically meaningful, tied to respiratory drive.

- Resting-state fMRI is feasible in the spinal cord—despite immense technical hurdles.

Since then, the field has advanced: higher-field MRI (3T and 7T), better motion correction, and standardized spinal cord templates (like PAM50) now allow more detailed mapping of spinal networks involved in pain, motor control, and autonomic function.

But it all started here—with a careful, thoughtful study that dared to ask: Does the spinal cord have its own “resting rhythm”? And the answer, remarkably, was yes.

This study reminds us that even the most “automatic” parts of our nervous system are humming with organized activity—and with the right tools, we can listen in.

The authors later went on to study another highly challenging region—the brainstem—and discovered a CPG-like mechanism underlying human walking.

Follow the Topic

-

European Journal of Applied Physiology

European Journal of Applied Physiology aims to promote advances in integrative and translational physiology to further understanding of the functioning of healthy humans.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Critical Power

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Energetics of Human Locomotion

This collection is aimed to present the foundations on energetics on human locomotion.

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in