The molecular structure of a supercharged flagellar motor inside the cell

Published in Ecology & Evolution, Microbiology, and Cell & Molecular Biology

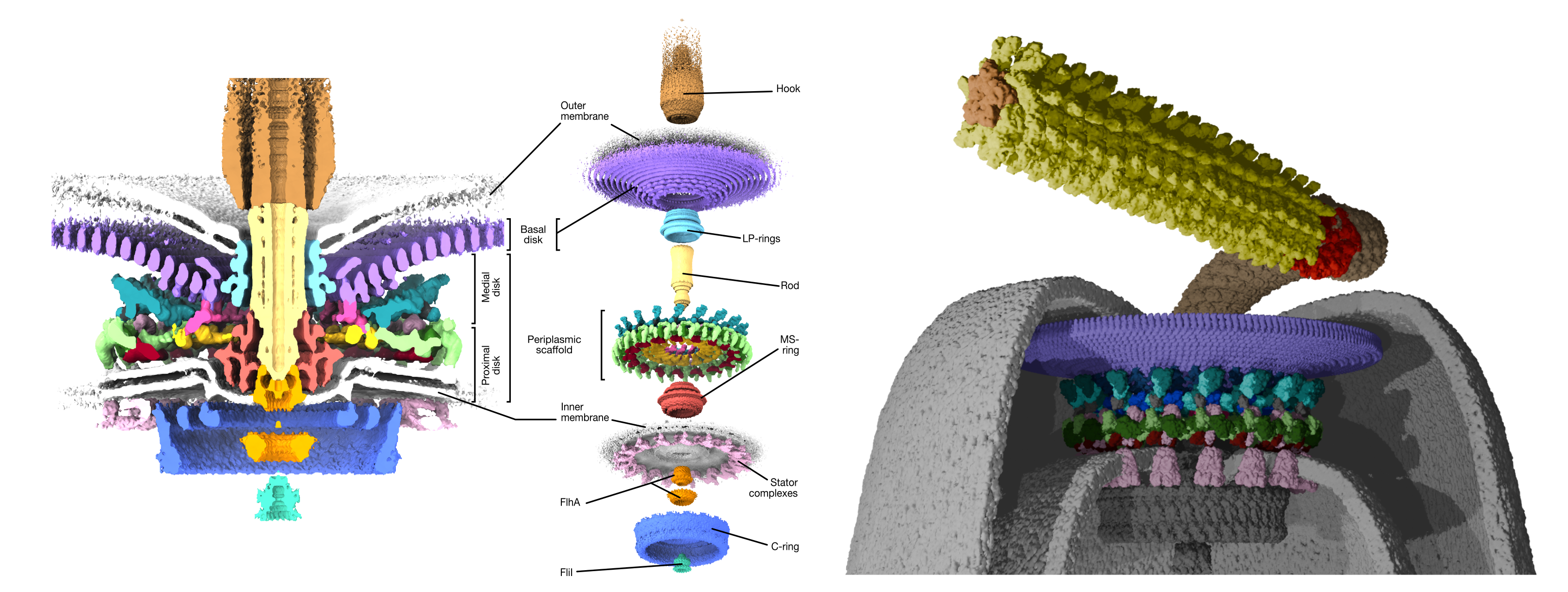

Bacterial flagella are long tail-like structures that, when rotated, form helical propellers. Driving rotation are flagella motors, nanoscale molecular machines embedded in the surface of bacteria that harness energy to rotate the attached flagellum. What is exciting about flagellar motors is that they are at least as diverse as the beaks of Galápagos finches. Indeed, diverse flagellar motors have added extra components, making them a prime model system for asking: where did these new components come from? How were they recruited to a pre-existing molecular machine? How were they retained? Over the years we have worked to identify these extra components, and the selective benefits of their addition – which is often to increase the torque of the respective motor.

To visualise flagellar motors, we use electron microscopes to image the motors intact inside cells. Specifically, we flash-freeze bacterial cells, enabling us to insert them into the high vacuum of an electron microscope without needing chemical stains or fixatives. This means that the images we collect in the electron microscope are of the biological molecules themselves, instead of stain. Although individual images are very noisy, sophisticated image processing algorithms enables us to combine the information from many thousands of images of flagellar motors to infer a single consensus 3-D structure. In theory, this can resolve the structures of biological molecules to atomic resolution. My lab’s aim is to achieve this goal, as molecular models of whole flagellar motors is invaluable to understanding their evolution by enabling us to precisely cross-reference structure and function to genetic changes.

The problem is, the thicker the sample, the lower the quality of the images, and thus the lower the quality of the final 3-D structure. Some protein machines can be studied by extracting them from the cell, but flagellar motors are so intricately interconnected with the cell superstructure that any attempt to remove them from the cell tears them apart. This has forced us to image flagellar motors in the relative thickness of whole cells, resulting in poor images and limiting our resolution to tens of Ångstroms – sufficient to see the overall shape of the flagellar motor, but insufficient to see anything meaningful about which protein molecules go where.

We’ve still been able to make progress, and have devoted most of our efforts to understanding the flagellar motor from the gut pathogen Campylobacter jejuni. The Campylobacter motor is particularly interesting from an evolutionary standpoint because it has added on so many additional components that it is twice the size of the better-studied motors from model organisms like Escherichia coli and Salmonella species. Working with the lab of Campylobacter expert Dave Hendrixson at UT Southwestern in Dallas, we have been able to work out the identities of many of these additional components, and to show that they function to position a wider ring of additional motor complexes around the motor, resulting in production of approximately three times higher torque and E. coli and Salmonella. This likely enabled Campylobacter to inhabit new niches in gut mucous, expanding its capability as a pathogen.

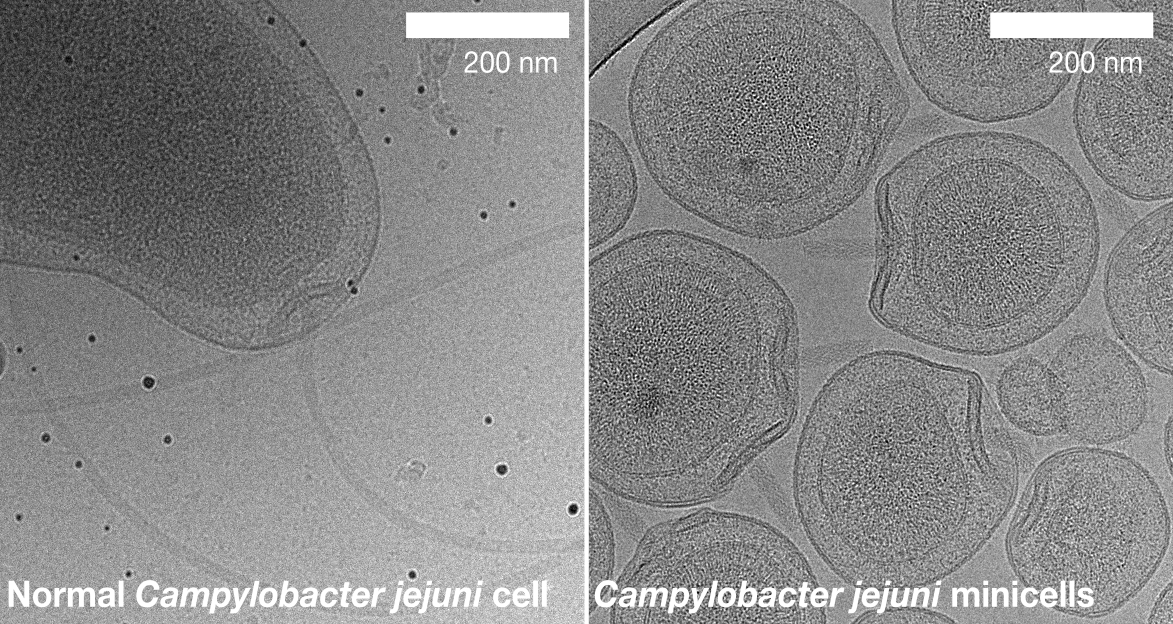

But we needed to increase the resolution of our 3-D structures. One possibility came from previous work in Dave’s lab: Dave had identified a mutant of Campylobacter that made extremely thin “minicells” due to a defect in their cell division. These minicells also included multiple flagellar motors compared to the single motor seen in normal cells. Long-term electron microscopy collaborator Peter Rosenthal and I wondered if we might capitalise upon this characteristic and purify large amounts of minicells for electron microscopy imaging. Not only would the images be of higher quality, but there would be many more flagellar motors per image. The combination might be revolutionary.

Eli Cohen, Research Fellow in lab, agreed to trial the approach. Eli genetically removed the flagellar filament, leaving minicells with multiple flagella-less motors which were easy to separate from the larger cells from which they originated. One day Eli came into my office: it had worked! Indeed, it had worked better than we had hoped, yielding images of lawns of minicells ripe for processing.

We went on to acquire a large dataset of images of these minicells. Tina Drobnič, then a PhD student in lab, took up the job of interpreting these images, and as the months passed we became more and more excited as Tina’s processing gradually improved the resolution of our 3-D structure.

To fully interpret our the 3-D structure we asked for help from collaborators. The high resolution of our structure revealed that there were additional components that we had yet accounted for. The lab of Cynthia Sharma in Würzburg, Germany, helped us to identify two of these additional components. Much to our delight, Cynthia’s contribution revealed that one of these components, “PflC”, is ancestrally related to an enzyme (PflC is derived from “Paralysed flagella protein C”). Enzymes are the factories of the cell, catalysing diverse chemical reactions. PflC is ancestrally related to a family of enzymes that digest incorrectly synthesised proteins. Curiously, PflC closely resembles this family of enzymes except in the region that catalyses protein degradation – this region has, instead, atrophied.

To fully interpret our findings, we worked with the labs of long-term collaborators Georg Hochberg in Marburg, Germany, and the joint lab of Francesco Pedaci and Ashley Nord in CNRS Montpellier, France. Georg helped us to understand the mechanics behind how an enzyme was repurposed to become PflC. PflC is one of the crucial parts of the scaffold structure that increases the torque of the motor, and Georg showed how parts of PflC form the large structural lattice. Meanwhile Ashley and Francesco elegantly sidestepped resolution limits in our structural data to show that while additional components have been added to increase motor torque, the core conserved components remain structurally unaltered.

As with all science, the excitement we felt with our study is not without limitations. The minicells were much better than previous cells, but our imaging approach was tooled specifically to focus on the large additional components, including PflC, which are responsible for increasing motor torque, and at the expense of our ability to resolve details of other parts of the motor. We have now set ourselves the challenge of imaging those other parts.

Although the study is a huge step forwards, this feels like just the beginning of an exciting new phase of work. What we now need is to produce a gallery of similarly high-resolution structures in a range of other species. Only by doing this will we be able to confidently infer ancestral states, and – we hope – working with Georg, who is an ancestral sequence reconstruction expert, recapitulate evolutionary steps in the lab. Think Jurassic Park. Just much smaller.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Microbiology

An online-only monthly journal interested in all aspects of microorganisms, be it their evolution, physiology and cell biology; their interactions with each other, with a host or with an environment; or their societal significance.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

The Clinical Microbiome

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 11, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in