The role of luck in creative career success

Published in Social Sciences

One of the crucial questions a movie producer, a scientist, or a musician, has to face during her career is: When will she produce her biggest hit? Can one predict when she will direct a blockbuster movie or make a fundamental discovery? Our research, with Roberta Sinatra and Federico Battiston, showed that this million-dollar question cannot be answered: the occurrence of the biggest hit is inherently random. This finding is also known as the random-impact-rule: Every creative product of an individual has the same chance to be the best, let it be the very first, or even the last piece of one's career. This finding is in line with Simonton, Sinatra et al., and Liu et al. as well.

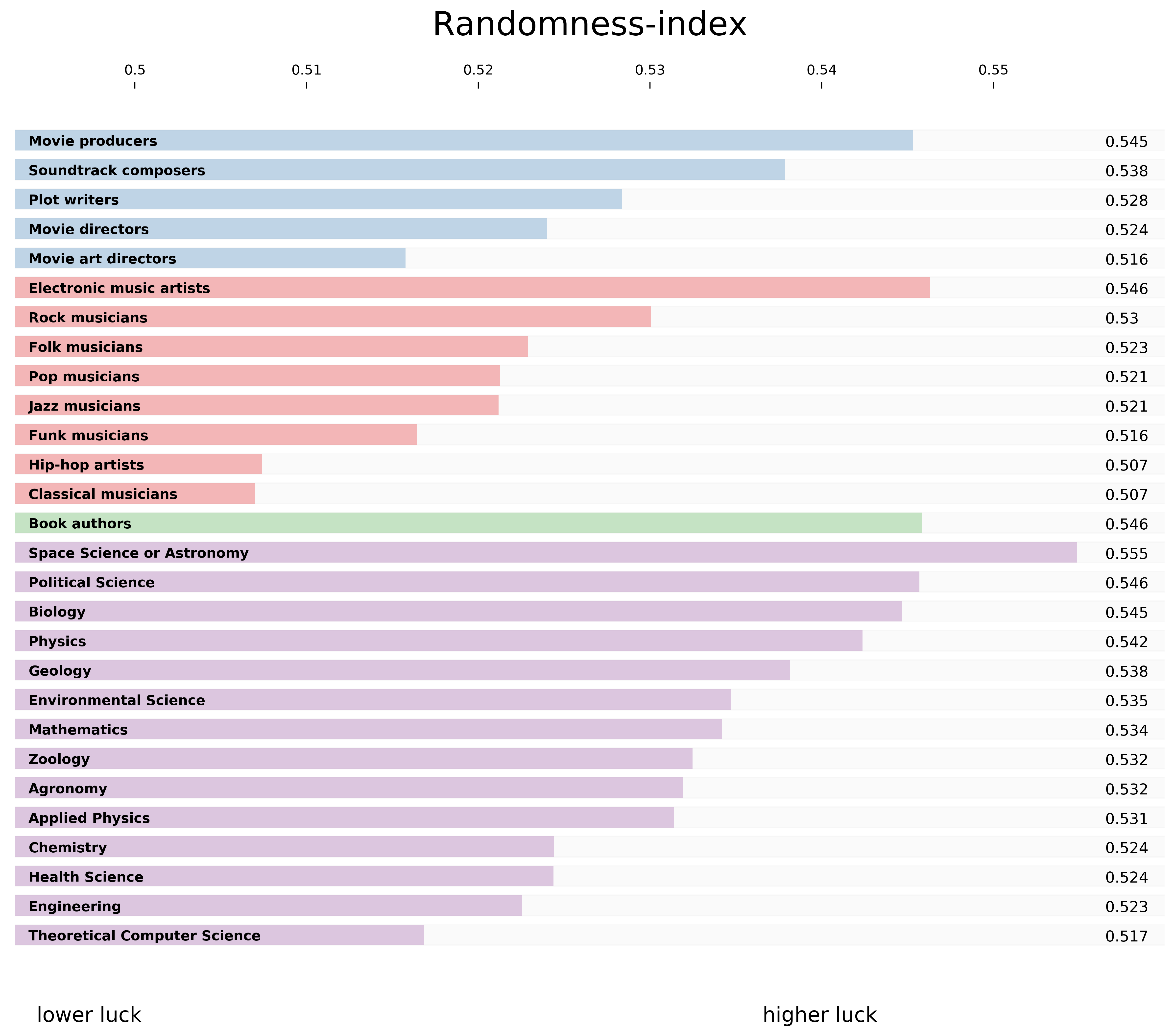

Apparently, luck is the main driving force behind the timing of the biggest hit. Then, the question arises: How does luck influence the magnitude of the hit? To answer this question we built on the random-impact-rule and on a formerly introduced modeling framework [rob], to decompose the impact of the individual products, such as books and movies, into two components: randomness and individual ability. We then compared the effect of these two components on impact across career 28 creative professions, ranging from movie directors to jazz musicians. Our findings, detailed in the second figure of our paper, uncover that randomness has a similar effect across creative domains and that its role is more pronounced than the role of the individual ability. In addition, our comparative analysis shows (Figure 1) that for instance, the musical fields most dominated by luck are electronic and rock music, while the least dominated one is classical music. For scientific disciplines, on the luck-end of the scale, we can find political science, contrasting to computer science which is the least exposed to luck.

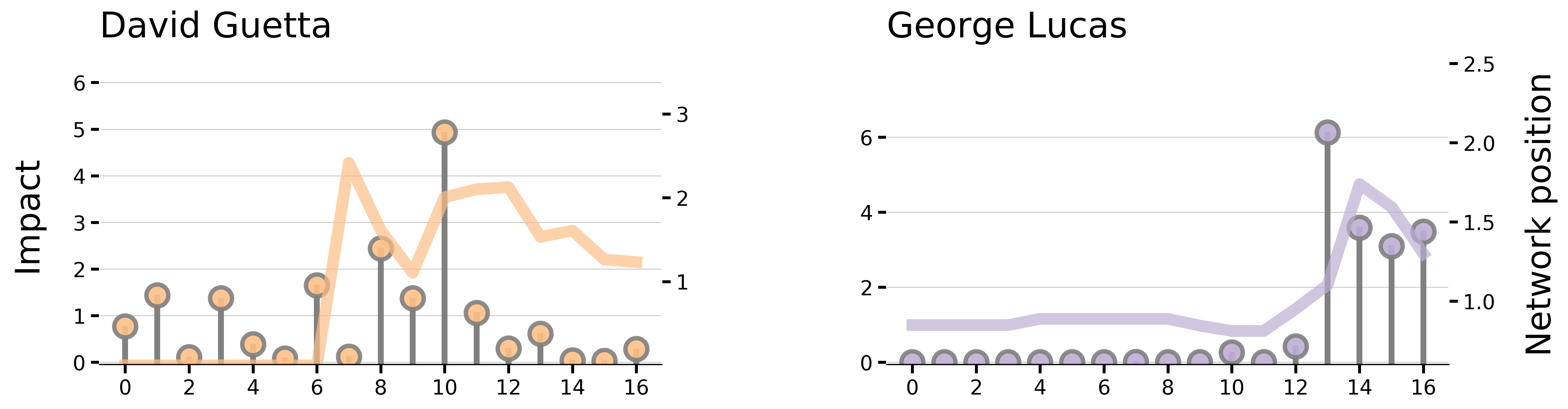

Finally, we investigated how the temporal changes in networking patterns may help to understand the occurrence of the big hit. Here our findings are twofold. First, we discovered that for creative individuals, two types of networking patterns exist. Namely, there are people who become central in their collaboration networks first, gaining access to connections and resources, and then produce their biggest hits. However, the opposite behavior exists as well: many produce their greatest piece first, any become central only afterward (Figure 2). Surprisingly, luck is still unavoidable: whether someone falls into the first or the second category happens at random.

Read more about this research here.

Follow the Topic

-

EPJ Data Science

This journal offers a publication platform to showcase the latest contributions to the study of techno-socio-economic systems, wherein the focus of the journal is on analyzing and synthesizing massive data sets to achieve new insights into societal phenomena and behavior.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Navigating Information Integrity in the Age of Misinformation

This topical collection seeks to explore the pressing issue of misinformation and disinformation through the combined lenses of Data Science and Network Science. Misinformation is a complex problem emerging from the interactions among individuals, media platforms, and communication networks, often leading to widespread societal consequences. Both fields provide powerful frameworks for understanding these complexities — Data Science through the analysis of large datasets and pattern recognition, and Network Science through the examination of interconnected systems and emergent behaviors.

The aim of this collection is to understand how false information spreads across various platforms and networks—social, communication, and technological — and to evaluate the structural properties, dynamic behaviors, and data-driven patterns that facilitate this dissemination. Misinformation spreads not just because of individual actors but through intricate and interconnected systems that amplify and accelerate its reach, creating cascading effects that are difficult to mitigate.

By bringing together cutting-edge research from both Data Science and Network Science, this collection addresses the challenges of detecting, mitigating, and managing the effects of false information across connected systems. Understanding how data patterns and network structures influence the spread of misinformation can provide key insights into developing interventions and strategies for reducing its impact.

We welcome submissions that employ data-driven methodologies, network analysis, or a combination of both to tackle issues related to misinformation and disinformation. All papers will undergo the standard peer-review process as followed by the respective journals. Authors can submit their manuscripts to either EPJ Data Science or Applied Network Science depending on their affinity to data science or network science. The editors of the collection will assess each manuscript to ensure the most suitable publication venue.

Submission Information: Authors should select the appropriate Collection “Navigating Information Integrity in the Age of Misinformation” under the “Details” tab during the submission stage.

This collection supports United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 4: Quality Education; & United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 06, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in