The Unequal Landscape of Civic Opportunity in America

Published in Social Sciences

To rebuild civil society as a site of democratic flourishing in America, we need to understand where civic infrastructure is deteriorating. These are the places where it is difficult for people to find opportunities to engage with others in their community. Our new paper utilizes administrative and digital trace data to map the civil society in the United States.

This paper builds on a broader project (called “Mapping the Modern Agora”) to emphasize the need for increased scholarly and public attention on the deteriorating civic infrastructure in America. Mapping civic infrastructure at this scale reveals patterns that were hitherto obscured. We find that the unequal distribution of civic opportunity is associated with pro-social outcomes like the emergence of mutual aid groups, vaccine hesitancy, and vaccine uptake during the coronavirus pandemic.

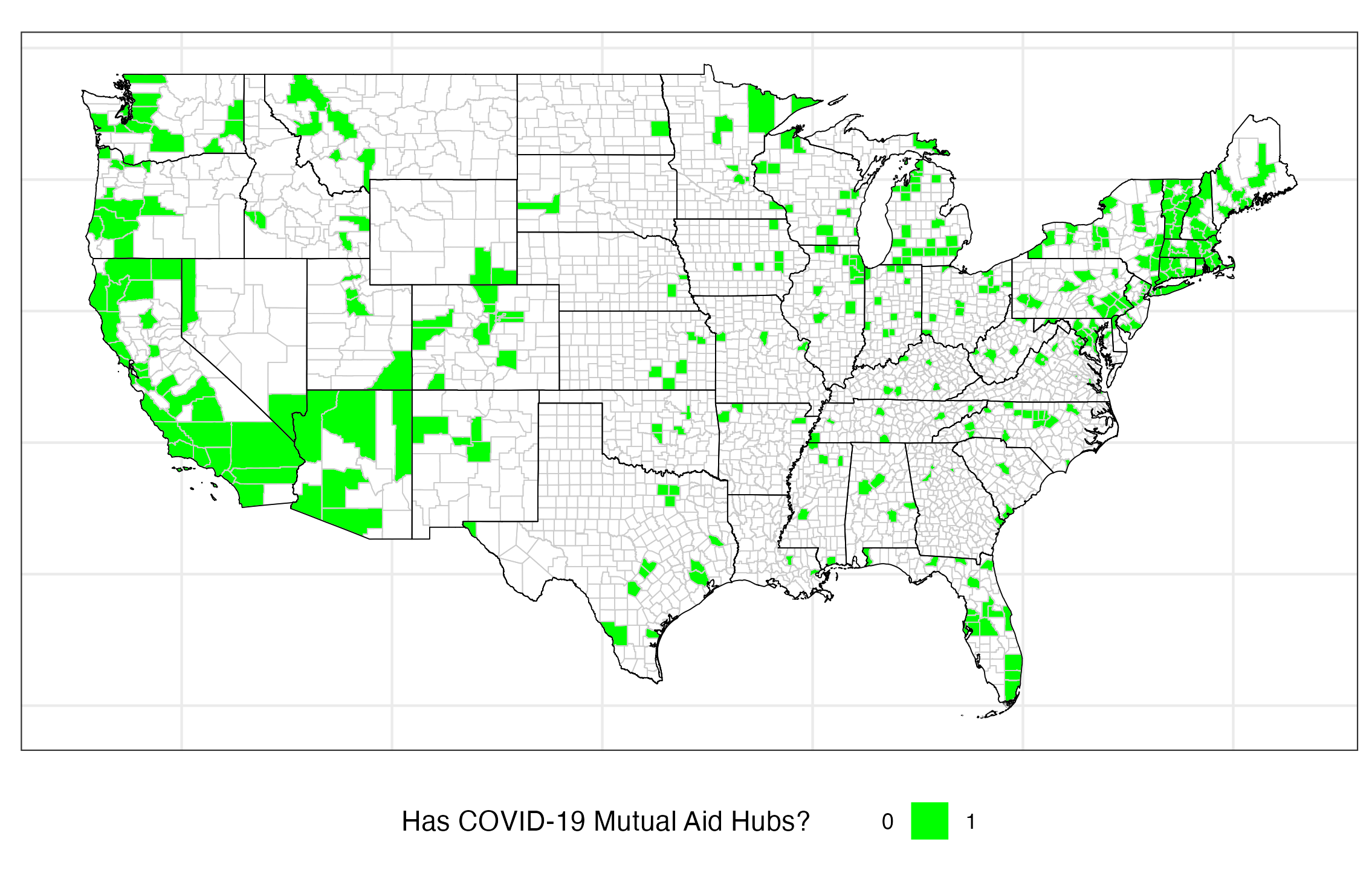

During the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous mutual aid groups emerged in local communities across America. These groups provided food and supplies to people in the community. In some cases, they also served as intermediaries between government programs and citizens, assisting people in accessing programs like SNAP (Supplementary Nutrition Assistance Program, the program that provides what are colloquially known as food stamps). These groups thus formed an integral part of the public effort to mitigate the pandemic crisis. They were widely praised by local and national media outlets as the silver lining of the pandemic. Plotting these organizational locations on a map raises the question of why their distribution is so uneven. As shown in the figure below, it is clear that these groups emerged in specific areas. Why were they more likely in certain communities?

The map of mutual aid groups during the pandemic in the US (Sources: Mutual Aid Wiki and Mutual Aid Hub)

Even in this age of technology, community action still revolves around fundamental skills of working with people, such as comprehending others’ concerns, hopes, and fears, strategizing possible solutions, mobilizing resources, and so on. These are basic civic skills necessary for democratic flourishing and historically practiced in the civic associations that have long characterized public life in America. These associations offer opportunities for people to participate in community events, interact with others, and cultivate civic capabilities. Our paper finds that places with high civic opportunity were more likely to see the emergence of mutual aid compared to places with low civic opportunity.

Previously, empirically testing the connection between a place's civic infrastructure and its civic response was challenging (if not impossible), due to the organic and decentralized nature of civic society. There is no readily available dataset of civic associations that researchers can consult to determine which organizations offer civic opportunity. As a result, scholars either relied on individual survey data (which minimized the role of organizations) or relied on proxy variables such as organizational density (the number of nonprofits per capita)--which failed to consider whether these organizations actually provided civic opportunity.

We overcame these limitations by bringing larger and more fine-grained data to the table. We used the tax returns that nonprofits filed with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). We then linked these 1.8 million tax documents to the websites of these organizations, as well as other demographic and socioeconomic data. This combination of administrative big data and digital trace data allowed us to map more than 560,000 organizations providing civic opportunities throughout America. We could also classify these organizations by type and activity. For example, we can identify whether an organization is a religious or a professional organization, and whether it offers volunteering opportunities, as well as opportunities for civic and political engagement. Such detailed data was previously hard for researchers to obtain at scale.

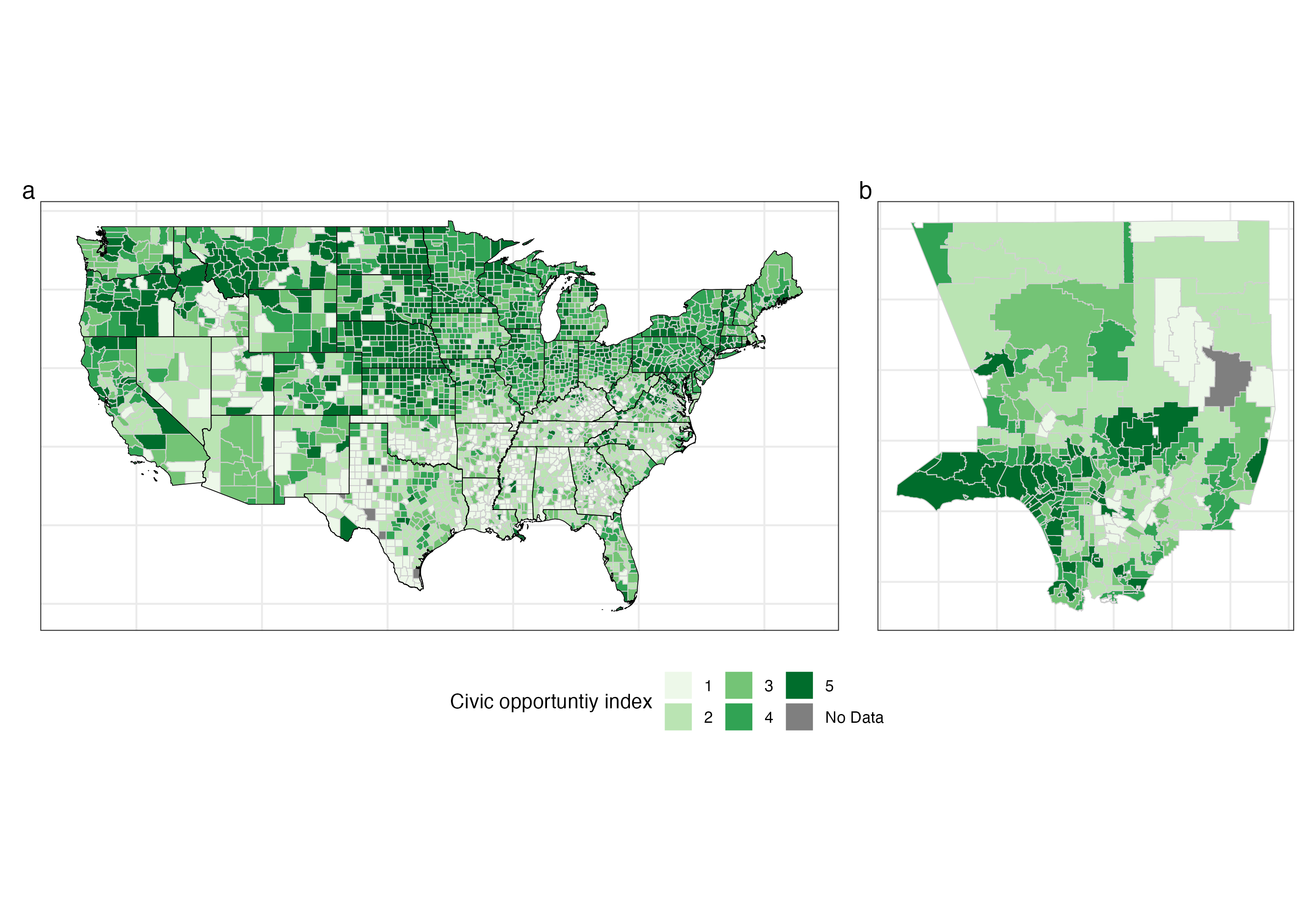

In the map below (which is Figure 1 in our paper), we have ranked places based on their civic opportunity scores. Panel A shows the rankings for counties, while panel B shows the rankings for zip codes within Los Angeles County. A score of 5 indicates high civic opportunity, meaning it is easy for people to find organizations that offer membership, volunteering opportunities, host public events, and engage in public and civic actions. Conversely, a score of 1 indicates low civic opportunity, where such opportunities are rare. These maps, and additional analyses in the paper, reveal persistent patterns of civic inequality.

Map of Civic Opportunities in the United States (Source: Mapping the Modern Agora)

In the remainder of the paper, we demonstrate that the unequal distribution of civic opportunity is systematic across the country. Communities that are better educated, wealthier, and predominantly white are more likely to have access to civic opportunities. Additionally, our paper examines the contrast between organizations that attract public attention and those that actually promote civic opportunities. For example, social-fraternal organizations (such as Rotary Clubs, fraternities, sororities, ethnic clubs, etc.) and religious organizations (churches, temples, mosques, etc.) make up 37% of all civic opportunity organizations. Furthermore, these types of organizations serve as the primary providers of civic opportunities in 85% of the counties. Although these local organizations often go unnoticed by the media, they play a crucial role in establishing and maintaining civic infrastructure in America.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Human Behaviour

Drawing from a broad spectrum of social, biological, health, and physical science disciplines, this journal publishes research of outstanding significance into any aspect of individual or collective human behaviour.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Digital Media and Mental Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Apr 15, 2026

Basic Psychological Needs and Well-Being

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Nov 27, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in