Welcome to the Anthropocene: How wildfire reality is eclipsing wildfire science

Published in Ecology & Evolution

In early 2019 I was invited to write a review article for the new online-only reviews journal Nature Reviews Earth & Environment. I excitedly accepted this invitation, as much because my lived experience mattered as my scientific research. Over the summer of 2018-19 Tasmania, where I reside, had just experienced a historically anomalous, protracted bushfire season causing the worst air quality ever recorded in that Australian state. That extreme severe fire season was on the back on large fires in 2007, 2013 and 2016, which collectively burned around 20% of the island.

Little did I know that the Tasmanian bushfire season was really a prelude to the truly enormous Australian bushfire season of 2019-20. It was enormous in so many ways: a huge geographical range from the Queensland subtropics to the Victorian temperate zone, a massive area of eucalyptus forest burnt, that is most likely historically unprecedented. The fires included period of very intense fire activity with over 30 fire thunderstorms (pyrocumulonimbus), which are typically rare wildfire events, and extreme smoke pollution that affected over half of the Australian population. Nor did I know that in late 2020 California would experience the second and third largest fires in that State’s history (the largest area burnt was in 2018). In all three cases there was a linkage between prolonged drought, extreme fire weather and lightning ignitions.

The primary objective of our Review was examination of the relationship between climate change and fire. To those outside fire science it may seem self-evident, and a somewhat trivial task, to show that climate change is causing a global fire crisis. I knew it is devilishly complicated. For that reason, I assembled an expert team of co-authors to help me build a comprehensive picture of the causes and consequences of recent fire activity around the globe, and the prognosis for future fire activity. The avowed method we took is synthetic, not analytic. I described this approach as pyrogeography, which we defined in our article as ‘the holistic study of fire on Earth achieved by combining and synthesizing knowledge and methods from the sciences and humanities.’ This is an ideal fit for Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, given the journal’s mission statement of ‘the latest advances in, and timely syntheses of, research spanning all aspects of Earth and environmental science, incorporating disciplines that fall within, and are related to, the following themes: weather and climate, surface processes, and solid Earth’ including the ‘reciprocal relationship between the environment and society’.

The Review turned into a major undertaking, given the complexity and diversity of the topics involved. Writing was interrupted as I was in high demand to provide media interviews and commentaries about the 2019-20 Australian bushfire crisis. In summary, producing a timely review about global fires was framed by global wildfire disasters.

Overall, in our Review we were able to conclude available science shows that ‘although there are large uncertainties, it is likely that the economic and environmental impacts of vegetation fires will worsen as a result of anthropogenic climate change.’ A primary reason this is a qualified and somewhat vague conclusion is because ‘detecting and predicting changes in fire activity is difficult due to relatively brief fire records, bioregional variability and human involvement.’ Indeed, the rate of change in global fire activity is highlighting the urgent need to get our act together and improve record keeping and undertake more rigorous analyses of fire events. This became painfully apparent with the inability to really settle on the magnitude of the Australian bushfires, a point other colleagues and I have argued in a recent Nature commentary.

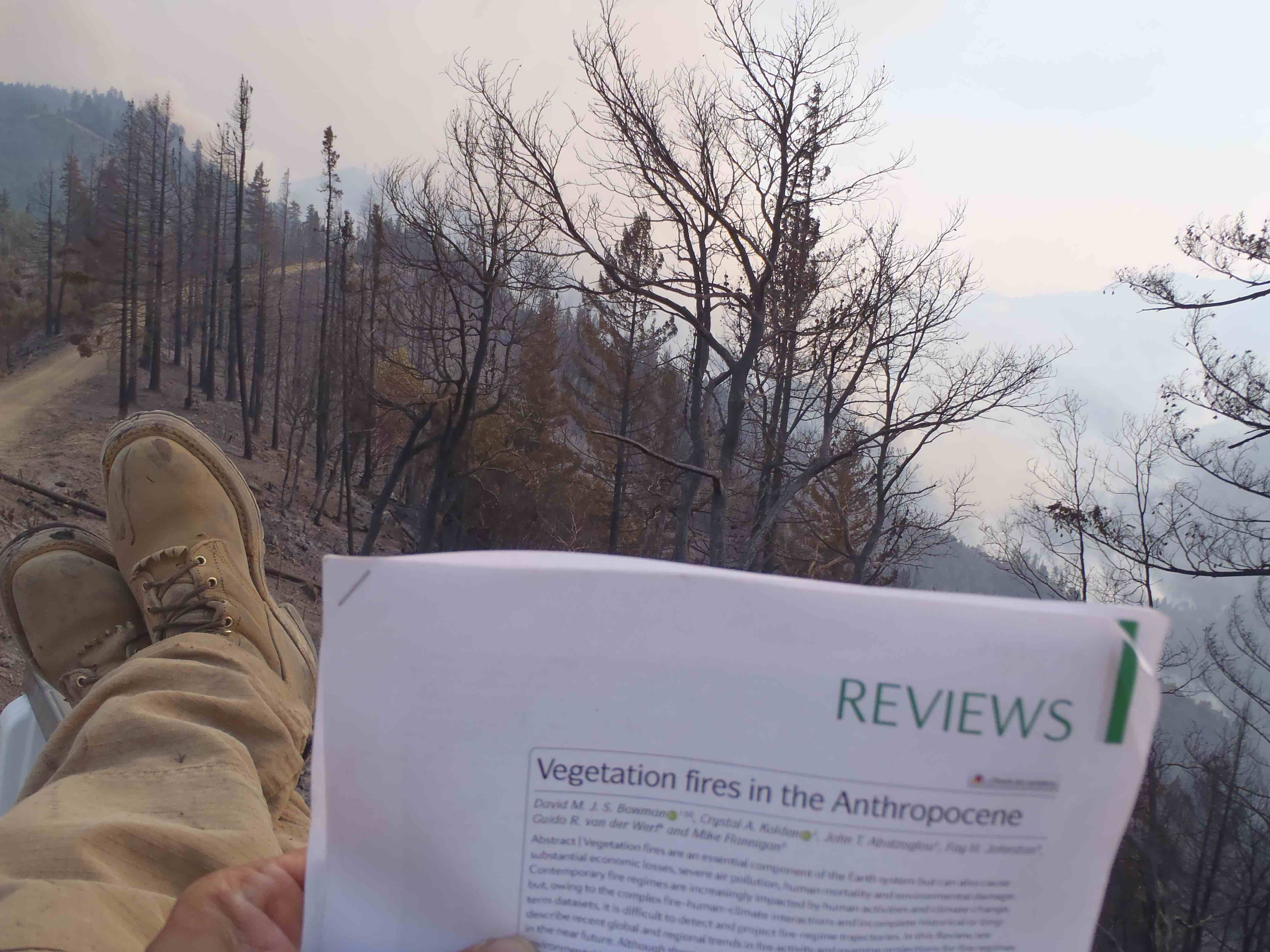

All authors face uncertainty as to whether a paper will make any impact, especially if the take home message is inconclusive. In our case we could not ‘prove’ the direct linkage between worsening wildfires and climate change.But here it is important to acknowledge the old adage ‘absence of evidence is not evidence of absence’. An email out of the blue from a frontline US forest fighter crystallised this point. He was reading our Review between missions on the fire front, motivated to find a coherent, synthetic explanation for wildfires that are outside his experience and professional expectations.

It seems a signature tune of the Anthropocene is that reality will routinely eclipse the accepted norms of experience and scientific knowledge. Seeing our work literally ‘held up’ before an ‘Anthropocene wildfire’ was a wonderful affirmation of both our synthetic approach and our broader findings.

My take home message is that we all, scientists, first responders and citizens who reside in flammable landscapes, are learning in real time about how fire activity is changing. We have embarked on a climate change journey. Accordingly, we are on a learning curve as to how to understand and adapt to worsening wildfire. Presently there is no conclusive ‘answer’ or resolution to the challenges that lie before us.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment

An online-only journal publishing high-quality Review, Perspective, and Commentary articles across the entire spectrum of Earth and environmental sciences.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in