What is physics? Challenges and opportunities when working at the interface with other disciplines.

Published in Physics

This year’s Berlin Science Week kicked off with a diverse programme. Among many events, visitors could discuss the connection between art and astronomy or learn how new technologies can be inspired by nature, or participate in a panel discussion at the Springer Nature office. The panellists set out to find an answer on how we define physics today, and to map out the boundaries with other related areas such as chemistry or biology.

Meet the panellists in our interviews from the run-up to the event: Abigail Klopper, Alba Diz-Muñoz, Cosima Schuster, Magdalena Skipper Beatriz Roldán Cuenya.

The event was introduced by the organiser Iulia Georgescu, Chief Editor of Nature Review Physics, which launches in January 2019. She announced the first review article of the journal had been published earlier that day. Fittingly, the piece discusses mechanobiology at the interface between physics and biology. Alba Diz-Muñoz, a group leader at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory, works at the same boundary between disciplines. She stressed the importance of getting another pair of eyes to look at your research as this will spark ideas nobody ever thought of. Alba Diz-Muñoz’s wrote a Perspective for the Insight on physics of living systems by Nature Physics, for which Abigail Klopper, a senior editor of the journal, was responsible. The Insight reflects how closely physicists and biologists collaborate, and how this collaboration benefits the quality of research.

Although the merits outweigh the disadvantages, interdisciplinarity might be problematic at times. Beatriz Roldán Cuenya is the Director of the Interface Science Department at the Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Society and works on the frontier of chemistry and physics. After obtaining her PhD in solid state physics, she moved to a chemical engineering department, and was surprised to experience discipline bias in publishing: when submitting a paper to a physics journal from a chemistry department, both editors and referees were unsure whether the research would fit in the scope of the journal. Cosima Schuster, program director in the German Research Foundation for the fields of statistical physics, soft matter, biological physics and nonlinear dynamics, is aware of this problem. When she looks for suitable referees for many of the interdisciplinary proposals, she aims for a diverse set of reviewers with a background in each of the disciplines. Although working at the boundaries of disciplines has many real-world implications, for the Editor-in-Chief of Nature, Magdalena Skipper, science is a continuum rather than a collection of disciplines, whose divisions are artificial.

In further discussion, the panellists exchanged their views on the state and future of peer-review in publishing. Some participants advocated for blind peer-review, not to be confused with single- or double-blind peer-review, where the reviewer or both reviewer and author identities are masked. Blind peer-review goes a step further by anonymising the authors to remove unconscious bias, and discipline bias, as pointed out by Beatriz Roldán Cuenya. However, as Magdalena Skipper pointed out, manuscripts under double-blind peer-review seem to be less successful than the ones having opted for single-blind peer-review. The question of how peer-review should evolve affects all disciplines. Related to this topic, a guest raised the question about the role artificial intelligence will play in publishing. The panel members seemed to be quite sceptical of the use of machine learning algorithms for example in the selection of suitable referees. From Cosima Schuster’s experience, one must often go off the trodden path when it comes to finding the best expertise to judge a paper, and this is something artificial intelligence cannot be trained on. Magdalena Skipper pointed out that although neural networks play an increasingly important role, Nature Machine Intelligence will launch with a team of human editors. She jokingly added that even the well-trained algorithms behind streaming platforms never suggest a movie she actually would like to see.

When the discussion moved back to the theme of the event, the question was how to initiate new collaborations between disciplines. Iulia Georgescu would like to see researchers asking more interdisciplinary questions, and Cosima Schuster encouraged researchers to go out of their comfort zone – whether within or across disciplines. Rather practical advice was offered by a listener: aim for a balanced group of researchers with complementary expertise, and make sure to define the single work packages clearly. The discussion concluded in answering the question the panel set out to answer: Physics is what a physicist does, and a physicist is someone who learns a certain way of thinking and can apply it to everything.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Reviews Physics

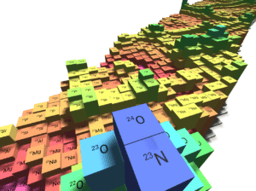

An online-only journal publishing high-quality technical reference, review and commentary articles in all areas of fundamental and applied physics.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in