Revisiting Europe’s agricultural past through a new suitability index

Published in Research Data, Agricultural & Food Science, and Economics

Climate change is not a recent phenomenon; its impacts have shaped human societies for centuries. From the Little Ice Age’s chill in the 16th and 17th centuries to droughts and flood events, shifting temperatures and rainfall patterns have long determined whether communities flourish or face hardship. Yet, how these earlier shifts played out across different regions remains only partially understood.

In pre-industrial times—before synthetic fertilizers or extensive irrigation—agriculture was particularly vulnerable; changes in weather patterns could destabilize entire economies by undermining food production. However, these drivers rarely act alone: temperature and precipitation interact in non-linear ways, and local soil conditions can amplify or mitigate extreme weather impacts. Historically, scholars often relied on single metrics—such as average temperature—to explore such events. When it comes to agricultural suitability indices, the usage was restricted to static information measured only at one point in time, primarily because time-varying agricultural indices were hitherto unavailable for pre-industrial times.

To overcome these limitations, we created a novel dataset of how “suitable” land was for farming across Europe from 1500 to 2000. Instead of cataloging where people actually farmed, we focus on what social scientists often call "exogenous conditions": local climate (temperature and precipitation) and soil characteristics (acidity and carbon content). By doing this, we separate natural constraints on agriculture from human decisions, offering a clearer view of how the environment itself shaped possibilities for cultivating crops.

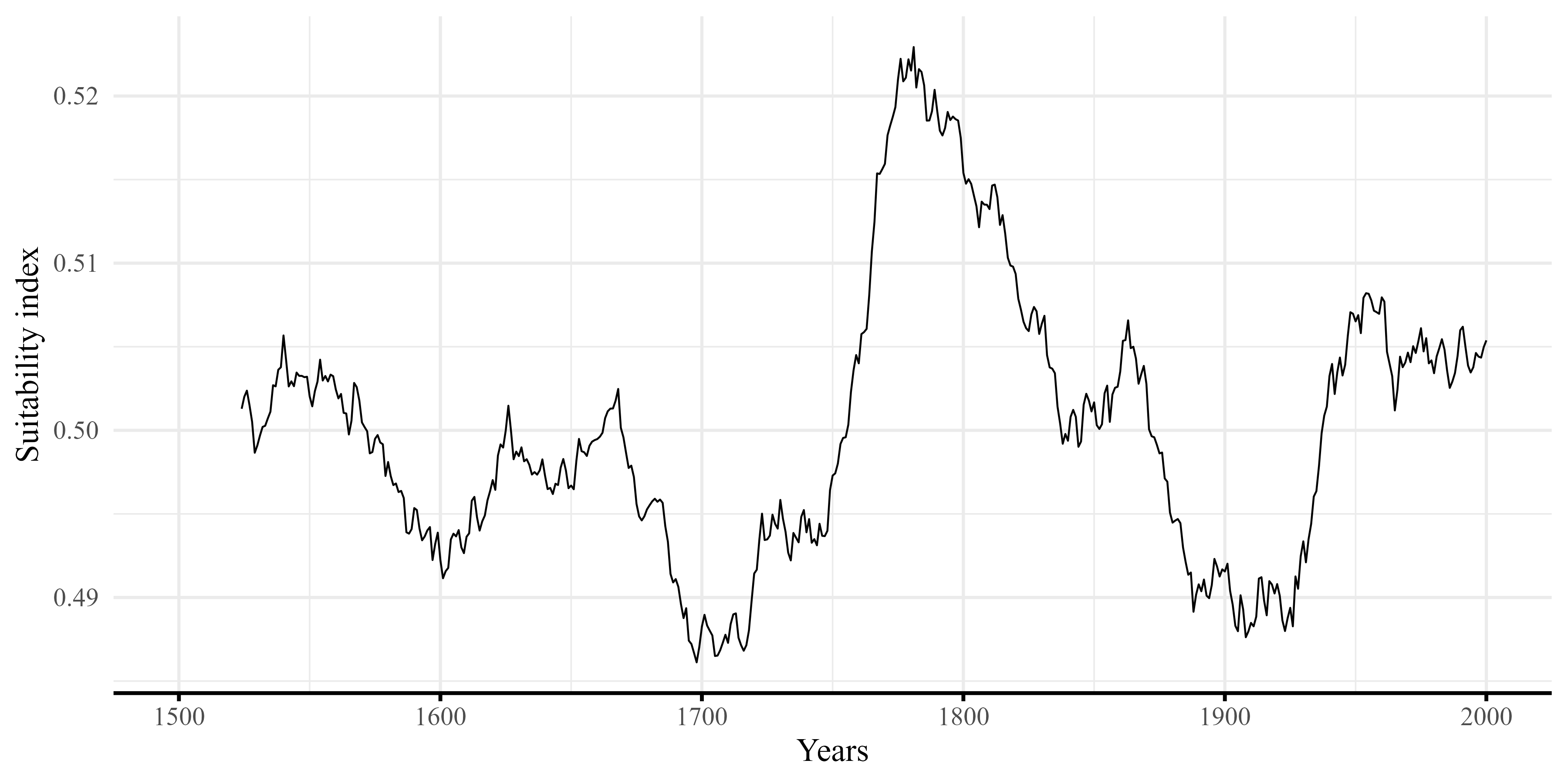

The index allows us to capture both long-term trends and short-term shocks. We can see how the cold phases of the Little Ice Age dragged suitability down for decades, but also pick up on individual years where weather patterns triggered local harvest disasters. These details can help explain why some regions thrived while others struggled at various points in history.

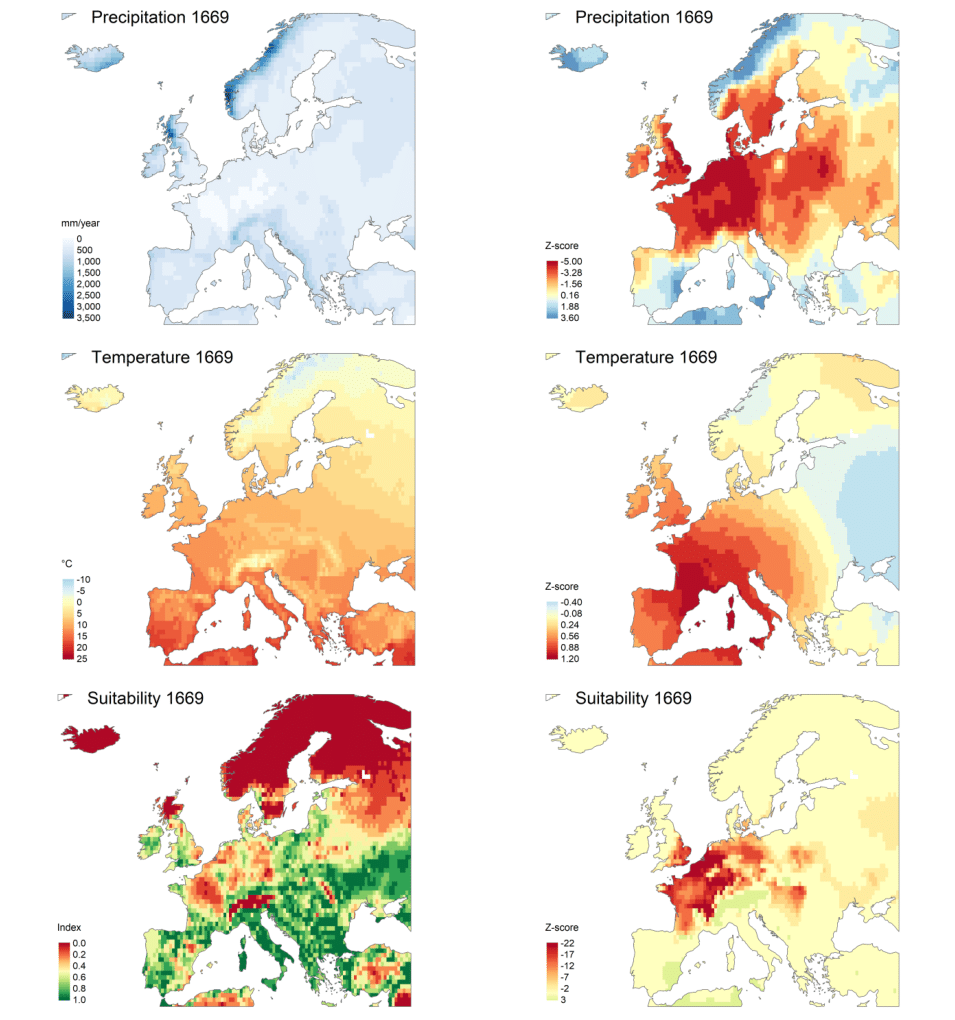

One striking example is the year 1669 (see Figure 2). While Western Europe enjoyed relatively high temperatures—potentially improving crop suitability—Central Europe was hit by extremely low precipitation, with some regions recording deviations of up to five standard deviations below their usual rainfall. This combination of warmth and intense dryness drained the soil of moisture, making large areas of land unsuitable for farming. On the other hand, in more arid areas of Southern Europe and Northern Africa, slightly higher precipitation offset higher temperatures, actually enhancing their overall suitability. These contrasting outcomes highlight why looking at temperature or precipitation alone can be misleading: only by jointly examining these variables, and capturing their non-linear interactions, can we properly account for the short-term weather shocks that shaped agricultural boundaries.

Beyond offering a window into the past, this work also informs how we think about climate pressures today. Modern farmers have more tools—irrigation systems, fertilizers, climate-resistant seed varieties—yet many regions still face climate-related threats. If a warming planet boosts growing conditions in one area, it might worsen drought risks in another. Learning how we historically coped (or failed to cope) can provide valuable lessons for ensuring food security and resilience in the face of ongoing changes.

While our understanding of past climates has advanced, much remains to be discovered. In many regions, paleoclimatic records remain sparse or unevenly documented. Tree-ring evidence, in particular, offers an invaluable glimpse into year-by-year climatic conditions, but large amounts of data remain unpublished or insufficiently georeferenced. Efforts to gather and unify these records—across broader geographical spaces and further back in time—would greatly enhance our ability to see how shifts in climate shaped societies.

Looking ahead, our approach could be extended to other parts of the world or further back in time. We believe it will prove valuable for researchers in fields such as history, economics, and environmental science, and hope that it will encourage greater collaboration across disciplines. By casting fresh light on how climate influenced societies in the past, we aim to strengthen our collective ability to anticipate and adapt to today’s rapidly changing planet.

Follow the Topic

-

Scientific Data

A peer-reviewed, open-access journal for descriptions of datasets, and research that advances the sharing and reuse of scientific data.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Data for crop management

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 17, 2026

Data to support drug discovery

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 22, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in