30-second nucleic acid purification

Published in Protocols & Methods

The current COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the powerful nature of molecular diagnostics to rapidly detect trace quantities of viral nucleic acid even in patients that are asymptomatic. Rapid and sensitive detection of pathogens is a critical first step that is needed to control the disease. However, the problem with molecular diagnostics is that they are expensive, time consuming and involve many steps requiring specialised laboratory equipment. The goal of our research is to develop new diagnostic technologies that are cheap, fast, and easy to perform.

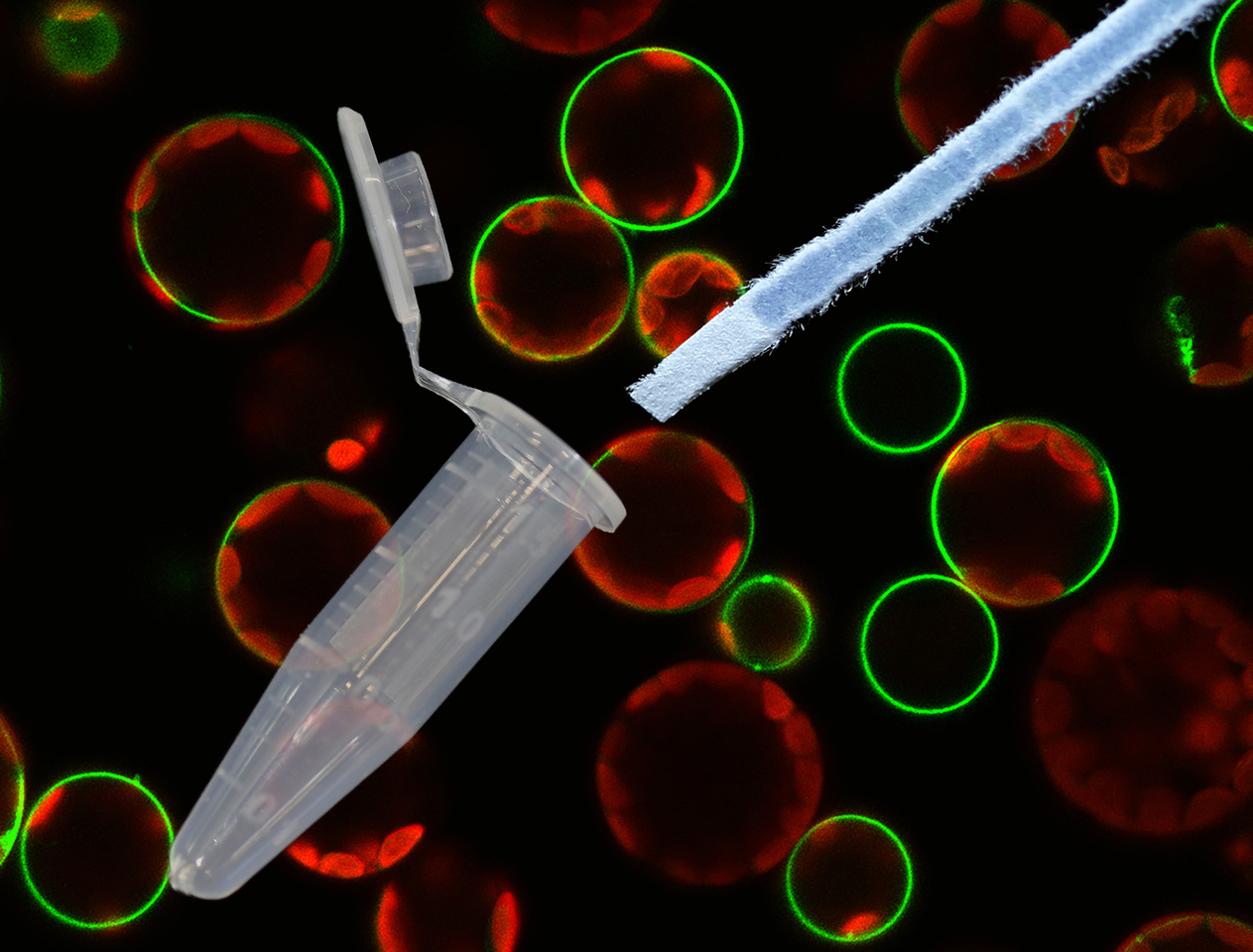

Our initial idea was to develop a low-cost DNA extraction technology using filter paper modified with chemical compounds that could help capture the DNA. While we were able to easily capture DNA with the chemically modified paper, we had difficulties amplifying the captured DNA in a PCR reaction. Like most discoveries, our rapid nucleic acid purification method did not come to life with a “Eureka”’, but rather a “That’s strange!”, when we realised that the negative control, that is, regular unmodified filter paper, was continuously outperforming the treated paper. Initially, we were sceptical, but my former PhD student (now a post-doctoral fellow), Yiping Zou performed countless nucleic acid purifications, and each time, the filter paper was able to retain the DNA during the wash step and elute it into the PCR reaction. It was so simple and fast, yet worked so well.

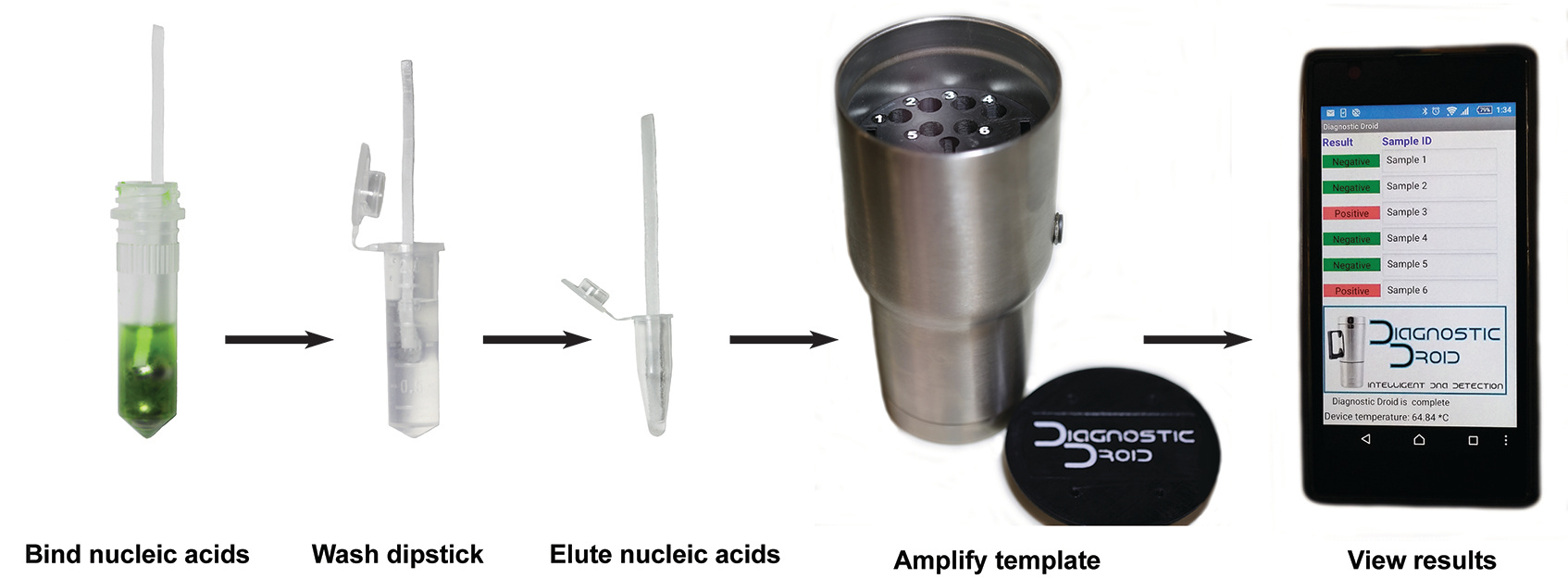

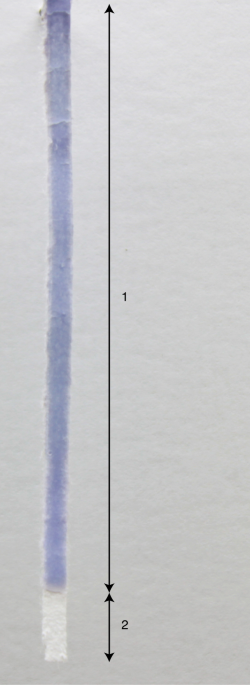

With our initial success with the filter paper-based nucleic acid purifications, it became apparent that we needed a convenient method to move the filter paper between the different solutions. While this could be achieved in many different ways, using a variety of materials, it was important to ensure that the method of manufacture was simple, low-cost and easily scalable. Routine diagnostic testing requires many nucleic acid purifications and I didn’t want to spend a lot of time making the purification devices. The idea I came up with was a hand-held dipstick as it could be quickly and easily moved between solutions. The dipsticks were made from wax-impregnated filter paper cut into thin strips using a pasta maker. I know this sounds a little weird, but there is method to the madness. The wax treatment is simpler than gluing filter paper to a separate waterproof handle and the pasta maker cuts the filter paper into identical, thin (2 mm wide) dipsticks that are the perfect size for use with 0.2 ml PCR tubes. Initially, I thought of using a paper shredder but I couldn’t find one that could cut the dipsticks as thin as the pasta maker.

Since developing the dipsticks, almost everyone I have met upon hearing about the dipstick method has a similar response; something like “It’s just plain filter paper, it can’t possibly purify nucleic acids”. To which, I always say that it only takes 30 seconds to do, just give it a go. As soon as people try the dipsticks, they are amazed at how quick and easy it is to extract nucleic acids. Unfortunately, this revelation is often accompanied by a brief period of regret with their sudden recollection of how much time they have spent in the past extracting DNA from countless samples for PCR analysis. I went through the exact same process myself, so I fully understand.

Today, it is not unusual for me to perform several hundred dipstick purifications a week. However, I do not find this particularly onerous, as it only takes me a few minutes to generate several weeks’ worth of dipsticks using the pasta maker and a stack of pre-prepared dipstick blanks (uncut wax impregnated filter paper). Additionally, I find the simplicity of the dipstick nucleic acid purification method streamlines the sample processing making it a far less daunting task. I always keep the sample extracts so that I have the option of performing a second DNA purification and amplification on the same sample if needed.

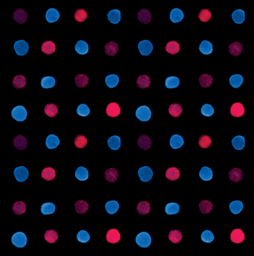

Another advantage of the dipstick purification method is that it can be performed almost anywhere as it does not require any equipment. I have successfully performed molecular diagnostic assays in remote locations by combining the dipstick purification with a portable DNA amplification device I built. The DNA amplification device automatically interprets the results for me so I can act on the information immediately. Typically, if I perform diagnostic testing away from the laboratory, I will aliquot all of the solutions ahead of time to avoid the need to pipette on-site but, I have also used disposable plastic eye droppers to aliquot solutions in the field. There are already reports from other research groups who have adopted dipstick purifications for diagnostic-based fieldwork and I imagine many more will follow, as the dipsticks are so cheap and simple to use; perfect for field-based applications.

The goal of writing the Nature protocols article (http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41596-020-0392-7) was to elaborate on the dipstick protocol and communicate my experiences with using them. I have personally found them indispensable for my work and I encourage others to give them a go. My hope for the dipsticks is that they help make disease identification a faster, simpler and cheaper process for everyone, especially those in low-resource settings. If COVID-19 has taught us anything, it is that time is critical for disease control; the faster diseases are detected, the faster management practices can be initiated to limit the spread of the disease.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Protocols

This journal publishes secondary research articles and covers new techniques and technologies, as well as established methods, used in all fields of the biological, chemical and clinical sciences.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in