A mind-bending take on the coloniality of global public health

Published in Microbiology

If Chris Nolan were to script a mind-bending global health story, it would probably look like "Epidemic Illusions," a new book by Eugene Richardson, an assistant professor of global health and social medicine at the Harvard Medical School. Richardson is a physician-anthropologist who has done extensive work on Ebola in West Africa and DRC. He has provided care to sick patients and also conducted anthropological research during the Ebola outbreaks.

Epidemic Illusions. On the Coloniality of Global Public Health. MIT Press, 2020

Like Nolan's movies, this book is complex, thought-provoking, weirdly formatted, and full of sub-plots and interwoven themes. Honestly, nothing about the book is conventional! Deploying a range of rhetorical tools, including ironism, “redescriptions” of public health crises, Platonic dialogue, flash fiction, and allegory, Richardson writes about what he calls an 'epidemic of illusions', an epidemic propagated by the coloniality of knowledge production. He argues that we do have the means to prevent and cure many of the biggest global health problems, but we don't. "Public health manages (as a profession) and maintains (as an academic enterprise) global health inequity," he argues.

Indeed, as Seye Abimbola and I have recently pointed out in a recent essay, "global health is a discipline that holds within itself a deep contradiction—global health was birthed in supremacy, but its mission is to reduce or eliminate inequities globally.” A growing number of people and groups are calling for global health to be "decolonized." While there are many dimensions to this complex issue, Richardson's book focuses on the coloniality of knowledge production.

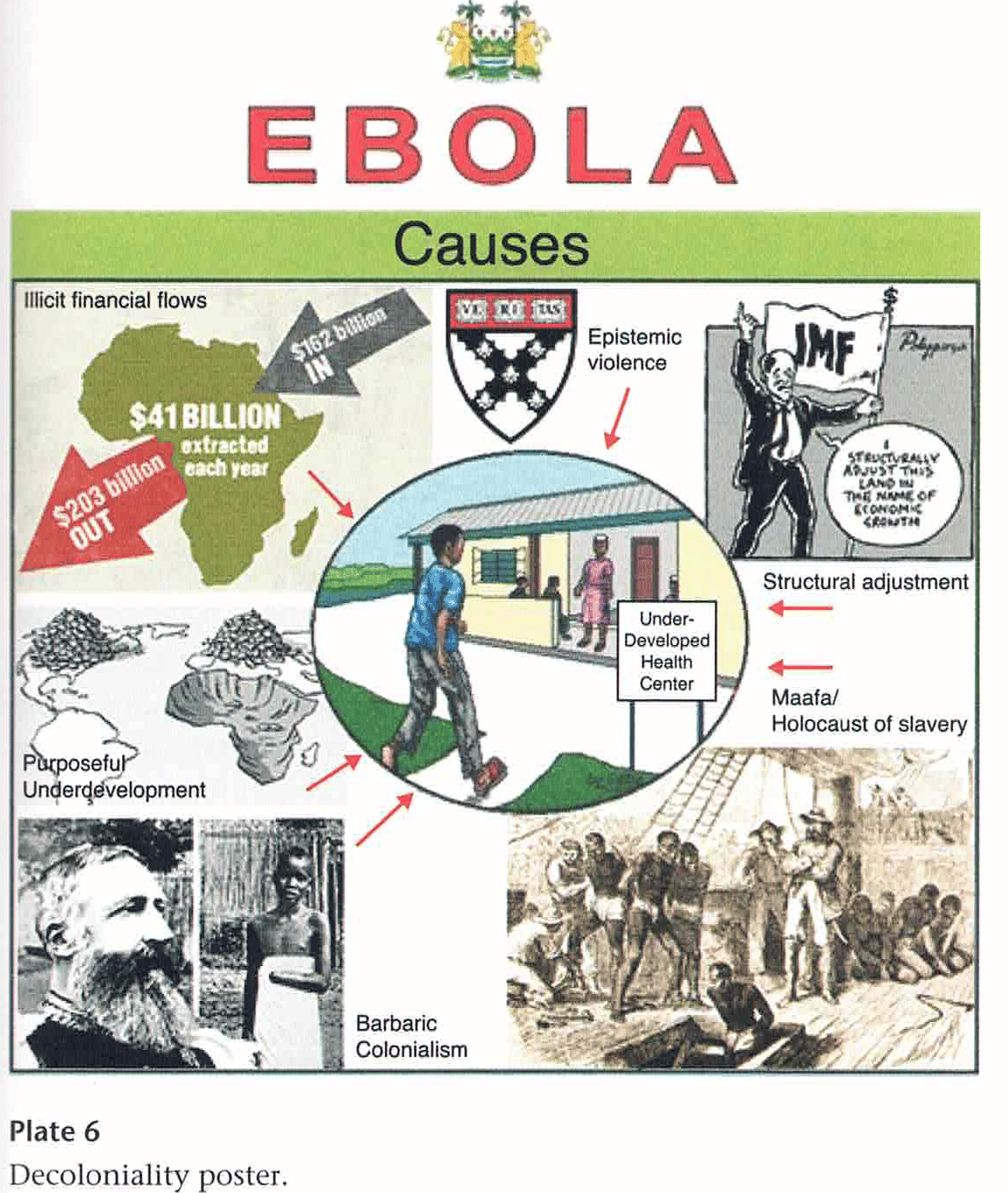

Richardson finds most epidemiological analyses and modeling studies to be devoid of any analyses of power. "For the most part, epidemiology as a method of science is considered apolitical; it actually serves as an ideological apparatus of imperialism by shielding structural causes of health inequities in the Global South," he argues. He provides several examples of epidemiological analyses of disease dynamics that fail to consider sociohistorical forces. In doing so, these studies end up diverting the public's gaze from legacies of colonialism, white supremacy, structural adjustment, institutional racism, and purposeful under-development which leaves health systems so weak and ineffective (below is Richardson's decoloniality rendering of a typical Ebola poster). Diseases such as Ebola thrive in these settings, and these upstream issues are more critical than issues such as burial practices or 'super-spreaders' that make the headlines.

Source: Eugene Richardson. Epidemic Illusions. On the Coloniality of Global Public Health. MIT Press, 2020 (with permission)

How might our analyses account for the above listed, upstream factors? Richardson offers a few fascinating experiments. In one modeling example, if Black women at high risk for HIV acquisition turned white and accrued the associated structural benefits, they could reduce their HIV incidence twelvefold, even as compared to biomedical interventions. In another example, Richardson and co-workers model the impact of reparations for Black American descendants of persons enslaved in the U.S. and their estimated impact on SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

The most fascinating, unique part of the book, in my opinion, is his use of the famous allegory of the cave in Plato's Republic. Using the Allegory of the Warren (figure below), Richard eloquently argues for us to move away from the notion of a universal truth (which, he argues, is at the heart of coloniality of knowledge, since it is predicated on Euro-American hegemonic epistemologies). To decolonize global health, "we must reject the notion that social inquiry can produce objective, value-neutral, and univocal understanding. Instead, we must embrace the critical and the polyvocal," he argues. "Through a pluriversal embrace of disparate ecologies of knowledge, we can begin to contain the epidemic of illusions that allows coloniality to thrive."

"The Warren" - illustration by Lena Gustafson, based on a design by Eugene Richardson (reproduced with the author's permission).

Although I found the book refreshingly different and genuinely thought-provoking, I was a bit puzzled by Richardson's particularly harsh critique of epidemiology (disclosure: I am an epidemiologist!). Every discipline (including anthropology) has its methodological limits or boundaries. It seems unfair to have crazy expectations that epidemiology alone can address all the upstream variables to describe complex problems in global health. And yes, shallow, superficial work without deeper analyses of power and socio-historical factors can result in biased conclusions and policies, but such superficial work can come from every discipline. Also, nothing prevents epidemiologists or mathematical modelers from broadening their models to include more upstream factors.

Epidemiology works well for certain types of enquiry (e.g. what is the efficacy of a new Ebola vaccine?) and is completely unsuitable for others (e.g. why are people hesitant to get vaccinated for Ebola?). The same could be said about every discipline. What epidemiology can do, anthropology or economics cannot. So, what we need is interdisciplinary work that brings together people with deep expertise in diverse fields (epidemiology, clinical medicine, anthropology, history, economics, political science) required to make sense of complex issues (Ebola or Covid-19, for example).

I shared my concerns with Richardson who clarified that he does indeed think that all forms of social inquiry merit the critiques in his book (including economics, political science, sociology, history, anthropology, etc.). While he discusses this at the end of the book, he agrees that it would have been wise to mention this upfront. He also clarified that he was primarily critiquing the elements of epidemiology that deal with human behavior. The actual science part— e.g. masks prevent COVID transmission, smoking causes cancer, vaccines prevent disease, etc.— he has no quarrel with.

Overall, Epidemic Illusions is a fascinating new book that breaks new ground (as Nolan did with movies like Inception and Tenet). It will likely confuse or frustrate many and piss off some. But, if you stick with it, it make you think, reflect, and critique conventional ways by which knowledge is generated and used. Global health researchers and practitioners will find it provocative and genuinely refreshing. Hopefully, it will also make them more reflexive about the ideological presumptions inherent in their own work. For his part, Richardson is reflexive about his own settler-colonist privilege and is unafraid to critique his own colleagues and university.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in