A neutral cyclic aluminium (I) trimer

Published in Chemistry

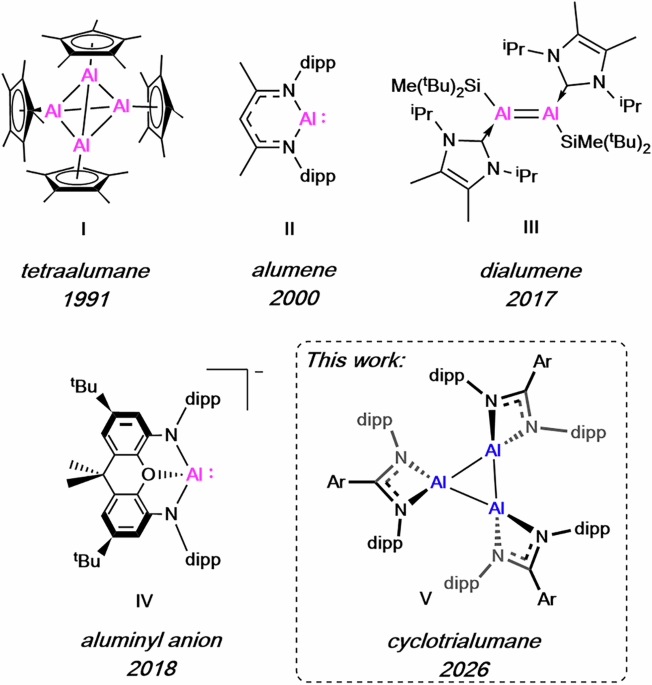

Low oxidation state main group compounds have grown from chemical curiosities to compounds of genuine synthetic use, with, for example, Jones and Stasch’s magnesium(I) dimer1 now routinely used as an inorganic reducing agent by synthetic inorganic chemists. As aluminium is the most abundant metal in the Earth’s crust, low oxidation state aluminium complexes are of particular interest. Aluminium(I) complexes2, with their two unshared valence electrons, have received a lot of attention as versatile, discrete two-electron reductants since the first reports of the tetrameric tetraalumane [AlCp*]4 in 1991.3 Since then, monomeric alumenes4, dimeric dialumenes5 and even species somewhere in between6–8 have been described (along with a range of charged aluminyls9), and a wide range of their reactivity has been explored. Trimeric neutral aluminium(I) fragments have been notable in their absence in the literature: the knock-on effect of this is that whilst there is a growing awareness of the flexible nuclearity in these systems10, no mechanistic investigation has thus far considered trimeric nuclearity. Furthermore, one consistent issue has plagued this field: the relative synthetic inaccessibility of these species, with challenging syntheses and low final yields having so far deterred the wider synthetic chemistry community from adopting these potent reducing agents.

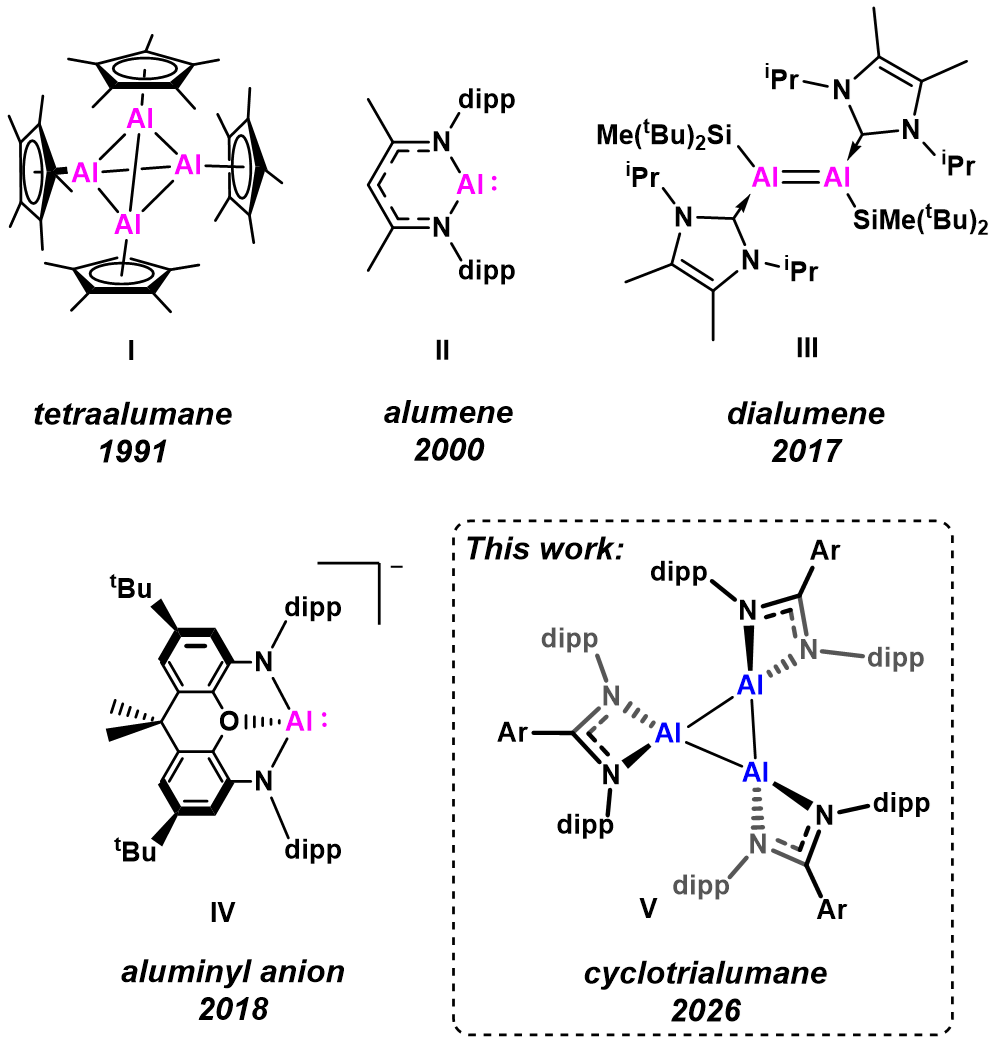

![]()

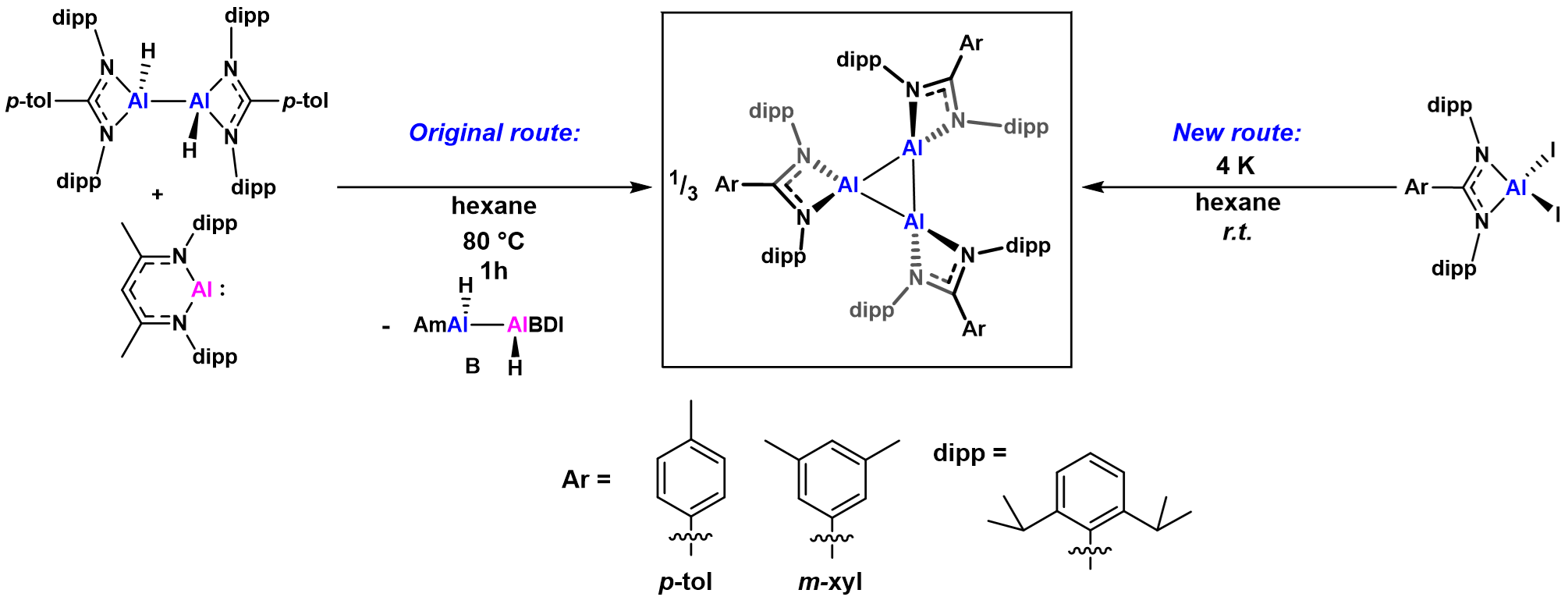

Figure 1: Examples of landmark aluminium(I) complexes. I Tetraalumane, Schnöckel, 1991; II Alumene, Roeskey, 2000; III Dialumene, Inuoe, 2017; IV Aluminyl anion, Aldridge and Goiceochea, 2018; V This work: Cyclotrialumane

In this work, we report the first examples of this elusive neutral, trimeric aluminium(I) complex, the cyclotrialumane. Through the judicious choice of anionic, bidentate supporting ligand, we have been able to favour the formation of a trimeric species, over the possible mono-, di- or tetrameric alternatives. We found our complexes possess covalent Al-Al single bonds, which are significantly shorter than those of the tetrameric [AlCp*]4, but longer than those of the doubly-bonded dimeric dialumenes. We have explored the reactivity of these cyclotrialumanes, with a range of small molecules. We observe that the cyclotrialumanes can react in three distinct fashions: with larger unsaturated organic substrates such as aromatic species or bulky alkynes we see our trimer reacting at elevated temperatures as a transient dialumene. Whereas with small molecules such as methyl iodide instead we observe apparent monomeric reactivity. However, with a mid-sized substrate such as ethylene trimeric reactivity is observed; here we have fully characterised the stepwise reaction of three equivalents of ethylene with the cyclotrialumane, forming mixed-valence 5- and 7-membered ring systems. The mechanism for this reaction has been fully elucidated and shows several key trimeric transition states.

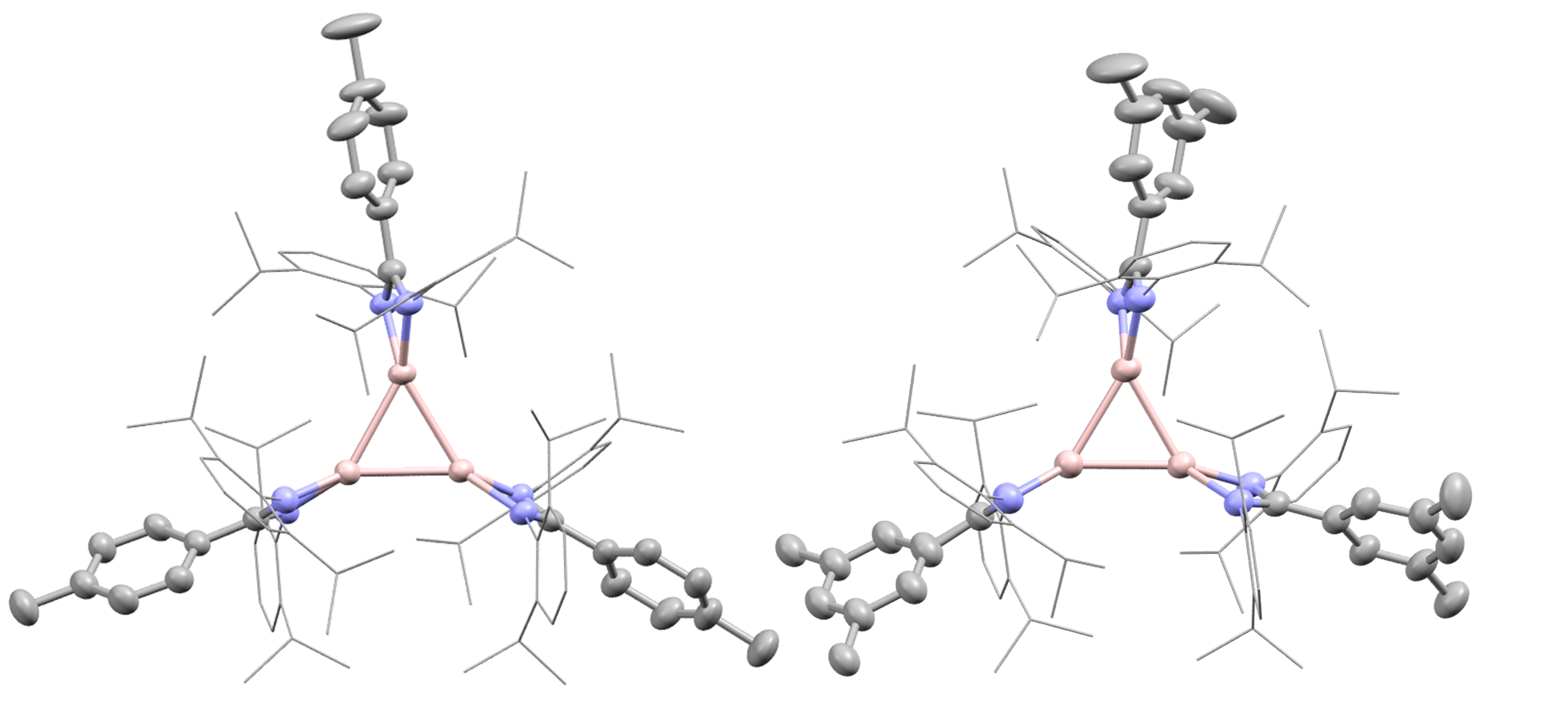

Figure 2: Cyclotrialumane crystal structures showing cyclic Al3 cores (pink: aluminium, lilac: nitrogen, grey: carbon; dipp groups wireframe for clarity)

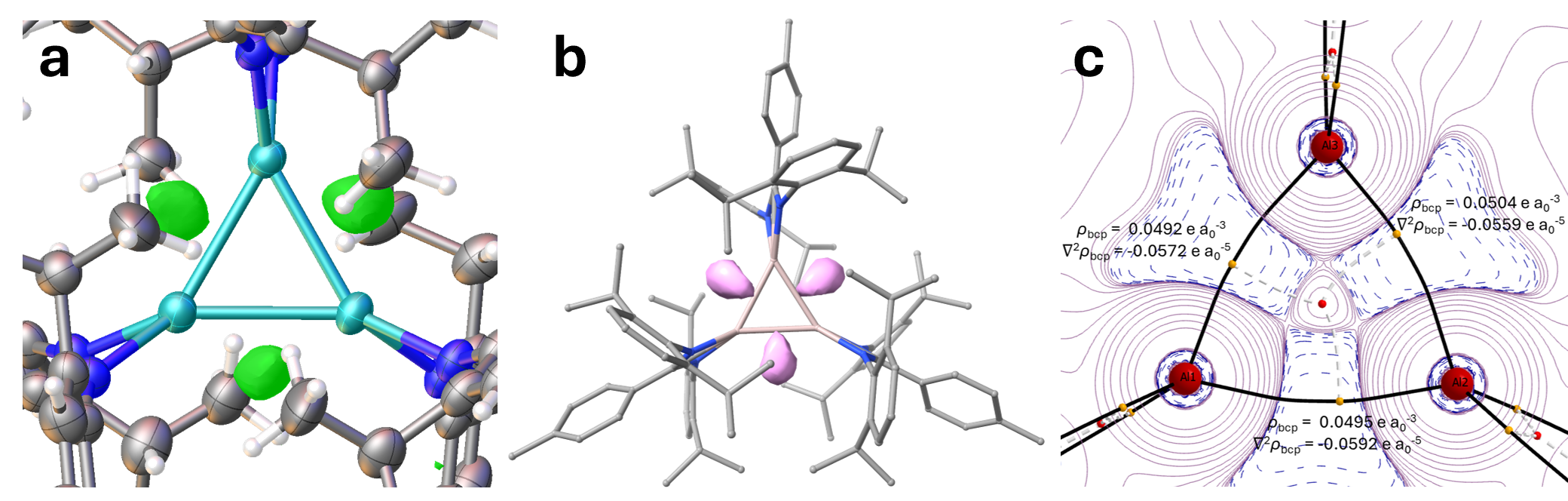

When we first synthesised what we have come to know as cyclotrialumanes, they were actually as one of many species present in a series of Al(I)-Al(II)-Al(III) redox reactions.11 Treating an amidinate ligand-stabilised Al(II) hydride (or, dihydrodialane) species with Roesky’s Al(I) monomer at elevated temperatures in aliphatic solvents resulted in the characteristic deep coloured solution with 1H NMR resonances indicative of the formation of the cyclotrialumane. However, when we crystallised this species, whilst we observed the amidinate-stabilised Al3 core, we noticed significant peaks of electron density between the aluminium centres, just off the linear bond paths. This was consistent, we thought, with the presence of hydrides. But that didn’t make sense! We had an apparently diamagnetic species (we could observe it via 1H NMR spectroscopy), but if there were hydrides between the aluminium atoms then we would have three Al(II) centres. As aluminium(II) has one unpaired valence electron, this would mean we could only have a radical (or triradical) species, which would surely result in a paramagnetic compound which should presumably be NMR silent.

The further hints that the assignment of this species as a trimeric Al(II) hydride was wrong came when we made efforts to model this putative species computationally. Despite extensive efforts, we were completely unable to find a stable ground state conformation. This prompted us to probe the electronic structure of the hydride-free species, with all computational evidence pointing towards an Al(I) trimer. The electron localisation function (ELF) data proved particularly interesting when interrogated: electron pair density of the Al-Al bonds was calculated to be located in regions coincidental with the same regions we observe the residual electron density (in the crystal structure). Furthermore, the Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM) calculations indicated strongly curved bond paths, again indicating why we may observe this strange crystallographic phenomenon.

Figure 3: Structural and electronic features of the cyclotrialumane. a: Residual electron density plot (green) from SCXRD data; b: Isosurface plot for the ELF of cyclotrialumane, visually highlighting the V(Al,Al) valence basins adjacent to the Al –Al bonds; c: QTAIM topology plot for the (negative) Laplacian of the electron density (- ∇ 2 ρ) highlighting areas of charge concentration (blue) and depletion (red) The values of electron density ( ρ) and ( ∇ 2 ρ) are highlighted at each bcp

Coupled with the reactivity (with no evidence of hydrides) and no signal when we probed the cyclotrialumane with electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy, all indications pointed to a cyclotrialumane. The final “smoking gun” evidence came when found we could access the cyclotrialumane via a different route. Reduction of the amidinate aluminium(III) iodides with finely divided potassium afforded the cyclotrialumane: no hydrides involved! The most exciting aspect of this synthesis was however the yields: for the meta-xylyl substituted congener, we isolated the cyclotrialumane as a crystallographically pure compound in a yield of up to 82%, indicating genuine synthetic utility!

Figure 4: The formation of cyclotrialumanes. The two different synthetic routes to the formation of the cyclotrialumanes (and our confusion!)

In conclusion, we present the cyclotrialumane - a novel aluminium(I) species with a hitherto unappreciated nuclearity. Within the group, we are now exploring the utilisation of cyclotrialumanes as reducing agents, probing the range of substrates and the mechanisms by which the cyclotrialumanes react with them, and increasing the scale of the cyclotrialumane synthesis. We are also expanding the range of synthetically accessible cyclotrialumanes and are investigating the effects of ligand modification on the cyclotrialumane structure and reactivity. We are excited about the future of this new tool in the synthetic inorganic toolbox!

References

1 S. P. Green, C. Jones and A. Stasch, Science., 2007, 318, 1754–1757.

2 K. Hobson, C. J. Carmalt and C. Bakewell, Chem. Sci., 2020, 11, 6942–6956.

3 C. Dohmeier, C. Robl, M. Tacke and H. Schnöckel, Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. English, 1991, 30, 564–565.

4 C. Cui, H. W. Roesky, H.-G. Schmidt, M. Noltemeyer, H. Hao and F. Cimpoesu, Angew. Chemie Int. Ed., 2000, 39, 4274–4276.

5 P. Bag, A. Porzelt, P. J. Altmann and S. Inoue, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2017, 139, 14384–14387.

6 R. L. Falconer, K. M. Byrne, G. S. Nichol, T. Krämer and M. J. Cowley, Angew. Chemie Int. Ed., 2021, 60, 24702–24708.

7 A. Lehmann, J. D. Queen, C. J. Roberts, K. Rissanen, H. M. Tuononen and P. P. Power, Angew. Chemie Int. Ed., 2024, 63, e202412599.

8 J. D. Queen, A. Lehmann, J. C. Fettinger, H. M. Tuononen and P. P. Power, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2020, 142, 20554–20559.

9 J. Hicks, P. Vasko, J. M. Goicoechea and S. Aldridge, Nature, 2018, 557, 92–95.

10 T. Chu, I. Korobkov and G. I. Nikonov, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2014, 136, 9195–9202.

11 C. Bakewell, K. Hobson and C. J. Carmalt, Angew. Chemie Int. Ed., 2022, 61, 2–7.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in