Beyond global hunger: The food people need may not be the food they can get

Published in Sustainability

Imagine going to your nearest food market only to find that the fish you want to cook up for dinner isn’t available at that market. Or the fish you want to buy is far too expensive for you to able to purchase. Both scenarios in which consumers cannot access specific foods pose concerns for food security and good nutrition.

Consumers must have both physical and economic access to food for it to end up on their dinner plate.

However, even then not all foods are created equal. Not only must consumers have physical and economic access to food, but they must have physical and economic access to nutritious foods.

In our study, bringing together physical and economic access to nutritious foods provides insight into getting the right fish on the right plate. This study signifies the need for a shift in fisheries policy focus towards fish species with greater nutritional value - not just high economic value - to better support the alleviation of food and nutrition insecurity. To increase consumers’ physical and economic access to fish, policymakers should consider geographically targeted strategies informed by the spatial analysis approach introduced in our study. For instance, investments may be made into improving road networks that are found to be critical fish transport routes linking beach landing sites to retail markets.

Getting the right fish on the right plate

Food and nutrition insecurity persists in every country on Earth, especially in the Global South. Malawi, located in sub-Saharan Africa, remains particularly challenged by food and nutrition insecurity. Although Malawi is landlocked, inlands waters, including Lake Malawi which is one of the African Great Lakes, play a critical role in providing affordable and nutritious aquatic foods to people vulnerable to food and nutrition insecurity.

Fish is one of the most traded commodities in the world and plays an important role in food security and nutrition around the globe. In Malawi, fish provides Malawians with critical micronutrients and is the cheapest source of animal protein in the country compared against other common sources of animal protein such as chicken and beef. However, not all fish contain the same nutrients, cost the same amount of money, nor are available in all the same markets.

A team of researchers at Michigan State University (MSU) and Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources (LUANAR) in Malawi investigated consumer access to two freshwater fish species with distinct nutritional profiles. Chambo, a large tilapia species, while generally viewed as the tastier option, is not as nutrient dense as usipa, a small pelagic sardine-like species. Understanding the nutritional value of each species helps to get the right fish on consumers’ plate.

Getting the right fish on the right plate

In the study, we developed a new spatial approach to map the distribution within the country of both chambo and usipa from Lake Malawi all the way to retail markets where consumers can buy the fish. This was made possible by integrating production, consumption, population, and geographic data, and adopting multidisciplinary approaches to synthesize and analyze this data.

Existing data on fish production indicate catch (production), but not whether the fish reaches those who need it. Similarly, consumption data describes who eventually ends up eating the fish, but not where it came from or how it reached them. We uniquely linked production and consumption by looking at where fish moves at each step along the value chain from production, processing, wholesale, and retail, all the way to household level consumption. First, we mapped connections between value chain nodes along the road network in ArcGIS Pro. Then, we created a 5-kilometer buffer zone around each retail market and overlayed Integrated Household Survey (IHH) data to identify how many Malawian households lay within 5 kilometers of a fish market. Finally, we assessed the annual income of all households within 5 kilometers of a market and compared it against the average cost of a nutritious diet per person per day.

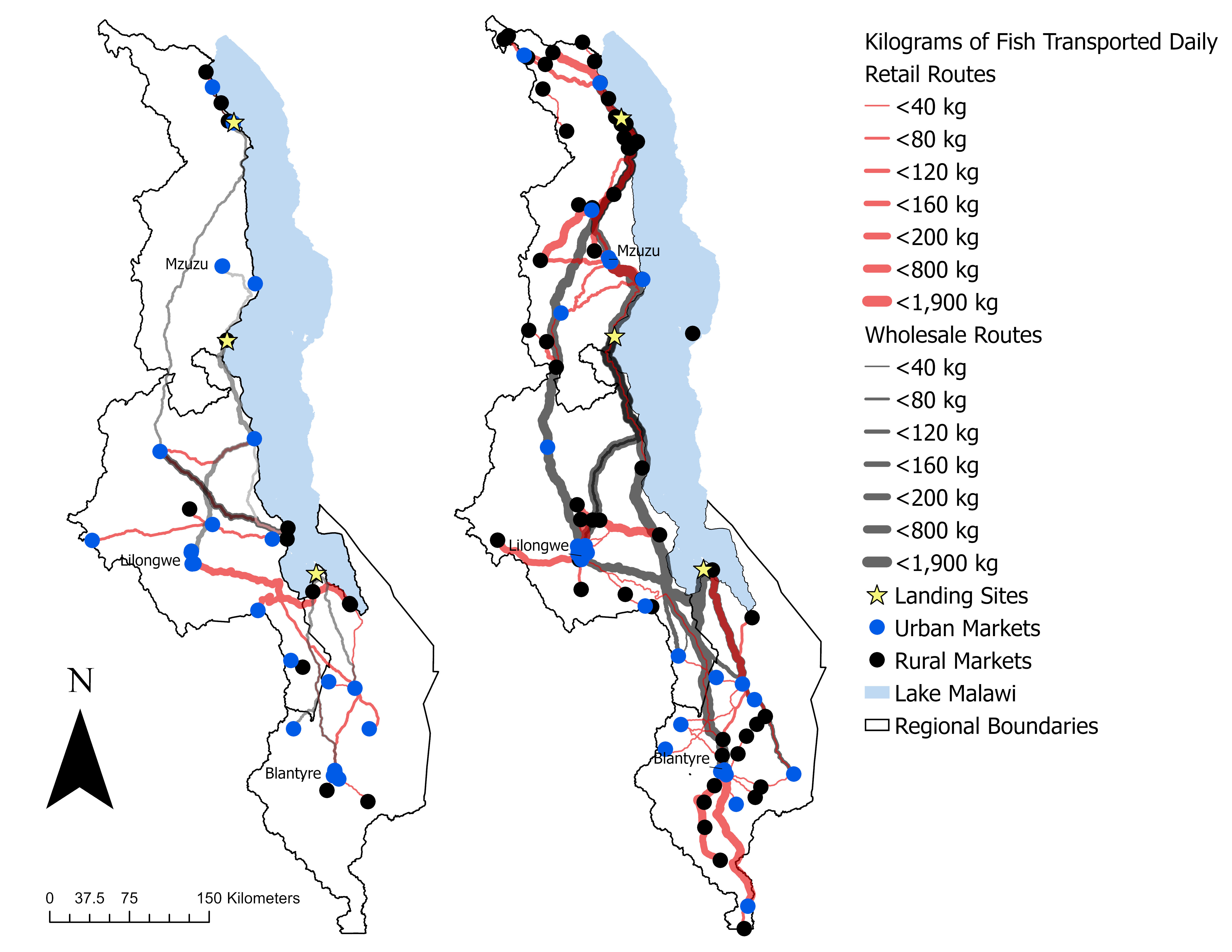

Compared to chambo, usipa is distributed to a much wider network of markets throughout Malawi. Usipa was available at 91% of the markets surveyed in the study, while chambo was only available at 20% of the markets [Fig 1]. Furthermore, the spatial analysis revealed that usipa is available for sale in more districts than chambo and is more available in rural markets than chambo, which almost exclusively serves urban consumers. In the context of food and nutrition insecurity, it is critical that nutritious foods are accessible to the rural poor as they are often the most vulnerable.

Not only is usipa more nutritious and more physically accessible to consumers than chambo, but it is also more economically accessible. Usipa is far cheaper per unit and per nutrient than chambo. Usipa is typically sold dried while chambo is typically fresh, and usipa catch quantity is much higher than the low volume chambo.

Given that usipa is more affordable and more physically accessible at rural markets to the people that need it the most, usipa is more effective than chambo at getting on the right plate.

Fig 1. Post-harvest flows of chambo (left) and usipa (right).

Beyond aquatic food systems

This work goes well beyond Malawi and can be applied to any geographic context around the world to better guide food systems policy towards nutrition-sensitive interventions. The innovative spatial approach introduced in this study can be utilized beyond aquatic food systems and can be adopted in any food system context to understand what type of food flows to which groups of people and through what mechanisms. This approach even has implications beyond food as it can be applied to any product value chain to spatially link production and consumption data to illustrate consumers’ physical and economic access to a given product.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Food

This journal aims to provide researchers and policy-makers with a breadth of evidence and expert narratives on optimising and securing food systems for the future.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in