Building a primary care chatbot with people, not for them

Published in Healthcare & Nursing, Computational Sciences, and Biomedical Research

If you’ve ever asked a chatbot a question and gotten a confusing or generic answer, you’ve touched the edges of a problem we sought to solve. Now, imagine your health depends on getting it right.

This was the central challenge of our research, recently published in Nature Health. We wanted to see if an AI-powered chatbot could address the critical shortage of primary care doctors in underserved communities. But we quickly learned that the real challenge wasn't just building a smart chatbot; it was building one humble enough to listen and adapt to the people it was meant to serve.

A crisis of access, not just technology

The statistics are stark, but they don't capture the full picture. In some rural regions, there is only one doctor for over 1,000 people. But the problem runs deeper than numbers. For many, primary care has been reduced to a quick transaction—often just dispensing medication. There’s little time for the continuous, coordinated care needed to manage chronic conditions, or for the health education that empowers people to manage their own well-being.

We knew AI could, in theory, help bridge this gap. But existing digital health tools were built for well-resourced hospitals and tech-savvy urban populations. They were like sleek electric sports cars being offered to communities that needed a rugged, reliable, all-terrain vehicle. Our mission was to build that all-terrain vehicle.

The dual-track role-play codesign framework

Our journey didn't start with a prototype of our own. It started with humility. We began by sitting with community members and exploring existing AI health tools. We asked a simple question: "How could a tool like this be useful for you?" The response was polite but clear: it wasn't. The tools were built on assumptions that crumbled in the context of rural life. They assumed a level of health and digital literacy, consistent high-speed internet, and a comfort with formal medical jargon that didn't align with the community's reality. The tools felt like they were speaking a different language—because they were. They were designed for a different world.

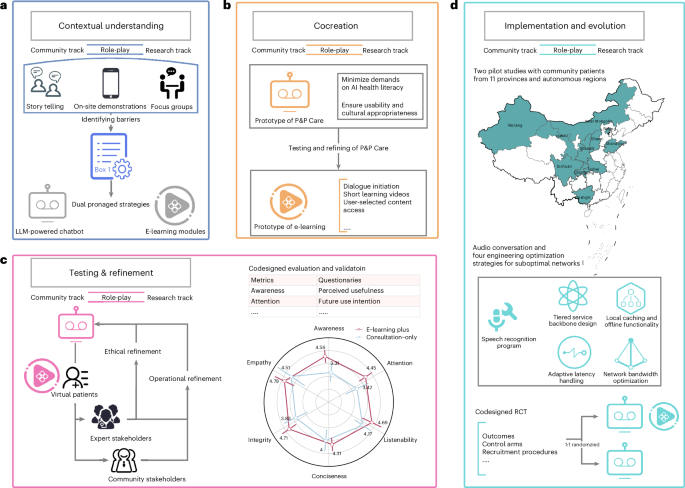

The turning point came when we decided to stop designing for communities and start designing with them. We created what we called a dual-track role-play co-design framework. While it sounds technical, the concept is simple:

- Community Track: Patients, caregivers, and local health workers defined the problems and shaped the solutions. They were the experts on their lived reality.

- Research Track: Our team of experts translated these community insights into technical reality.

The real magic happened in the role-play sessions. Our engineers had to step out from behind their computers and simulate being an elderly patient with low health literacy, struggling to describe their symptoms. In return, community members took on the role of designers, critiquing our prototypes with a simple but powerful question: "Would I actually use this?"

The untold stories from the ground

This process was filled with humbling and insightful moments that no algorithm could have predicted.

In one co-creation workshop, an older woman taught us a critical lesson. She explained that her biggest fear wasn't the AI being wrong; it was not knowing how to start the conversation. "I don't want to say the wrong thing," she said. This single insight led us to create a short, video-based tutorial on how to begin a dialogue, which became one of the most valued parts of our e-learning modules.

(Image: Photos from the codesign process, showing community residents talking about their concerns.)

(Image: Photos from the codesign process, showing community residents talking about their concerns.)

Later, during a pilot in a mountainous region, we hit a major roadblock. The consultation completion rate plummeted to 40%. The problem wasn't the chatbot; it was the internet. Unstable, slow connectivity in these areas made our chatbot unusable. Driven by this community-identified barrier, our engineering team developed a tiered service backbone that allowed the chatbot to shrink its digital footprint when networks were poor, and we added offline functionality for crucial tasks. It wasn't the most glamorous AI innovation, but it was the one that made the tool actually work where it was needed most.

(Image: Photos from rural pilot sites, showing community residents using their smartphones to interact with the chatbot .)

The ripple effect: more than just a chatbot

The results of our randomized controlled trial, involving over 2,100 participants, showed that our co-designed system significantly improved health awareness and consultation quality. But the numbers only tell part of the story.

The most profound outcome was the shift in power and capability. We saw participants, especially older adults, gain confidence not just in using the AI, but in understanding and managing their own health. The preparatory e-learning modules didn't just teach them how to use a tool; it equipped them with knowledge, turning them from passive patients into active agents in their care.

This is the true meaning of health equity. It’s not about handing down technology from on high. It’s about creating a process where community voice and expertise are embedded into the very architecture of a solution. Our co-design framework ensured that P&P Care wasn't our chatbot; it was their chatbot.

Looking forward

This journey taught us that the future of equitable AI in healthcare isn't just about building better models; it's about building better relationships. It's about creating a continuous dialogue where technology evolves with the community it serves.

Our hope is that this approach can be a model for others. The most sophisticated intelligence we encountered wasn't in our algorithms, but in the communities we were privileged to work with.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Health

Nature Health publishes health research across the medical, social and environmental sciences and requires meaningful engagement with research participants and their communities.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in