Why building AI for healthcare requires stakeholders, not just a dataset

Published in Healthcare & Nursing, Computational Sciences, and Biomedical Research

.png) (Image: Photo shows patients waiting in the waiting room of hospitals for secondary care; the majority are self-referrals.)

(Image: Photo shows patients waiting in the waiting room of hospitals for secondary care; the majority are self-referrals.)

When we set out to build an AI assistant to help patients transition from primary to secondary care, we thought our biggest challenge would be technical. We had access to a powerful, large language model (LLM) and thousands of recorded conversations between primary care doctors and patients. The conventional path seemed clear: feed this local data into the model so it could learn how people in these communities talk about their health. It seemed like the most direct way to make the AI “fit in.”

But our codesign workshops revealed a dangerous flaw in this plan. A community health worker put it bluntly: “If you train your AI on our old conversations, you will just teach it our old problems.”

That moment was a turning point. It forced us to confront a critical question: Should AI simply reflect the reality of a healthcare system, or should it help us reform it? This is the story of how we learned that for AI to be truly equitable, the process of building it is just as important as the final product.

Passive data harvesting

The standard approach in AI development is to gather as much data as possible—a process we call passive data harvesting—and use it to train a model. In our case, this meant collecting dialogues from busy rural and urban clinics.

On the surface, this makes perfect sense. You want the AI to understand local dialects, common symptoms, and cultural contexts. The problem is, real-world clinical data is messy. It’s full of interruptions, jargon, and the inherent shortcuts that overworked doctors are forced to take.

In under-resourced clinics, village doctors may lack access to the latest specialist knowledge or advanced diagnostic resources. The medical dialogues we collected, while thorough in their own context, reflected this reality. They contained the local, existing standard of care, which could sometimes miss subtle signs of complex illnesses or lack the nuanced questioning a specialist in a tertiary hospital might use. If we trained our AI, which we called PreA, on this data, it would learn to replicate these shortcuts. It would become very good at mimicking an overstretched system, potentially missing subtle signs of complex illnesses or reinforcing existing biases. It would be efficient, but not necessarily good.

We realized we were on track to create a tool that was perfectly optimized for a broken status quo.

.png)

(Image: The two-panel image depicts village doctors in action. The left panel shows a doctor delivering intravenous therapy, while the right panel features a doctor conducting a manual examination of a patient's waist as other patients wait their turn nearby.)

The codesign journey

Instead, we committed to a more complex but ultimately more collaborative approach: codesign. As outlined in our recent Nature Health paper, this community-participation framework meant the community were not subjects but core partners, actively shaping and critiquing the design at every stage.

Our multistakeholders included patients, family caregivers, community health workers, nurses, primary care physicians, and specialists from 11 provinces across China.

Codesign versus data tuning

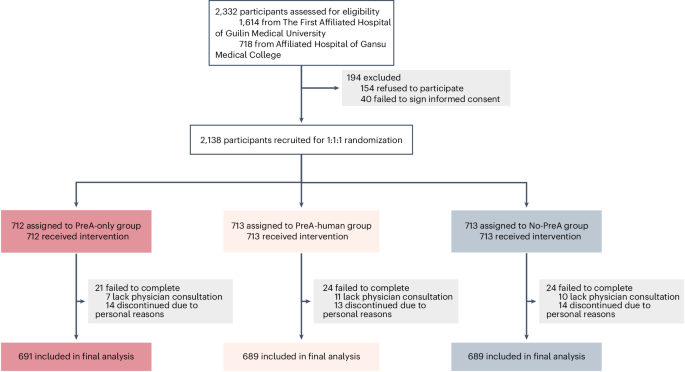

So, did this intensive, village-driven approach actually make a better AI? To find out, we ran a head-to-head comparison.

We created two versions of PreA: the codesigned model (shaped by the contextual understanding and cocreation with communities) and the data-tuned model (the same base model, fine-tuned on the raw, passive local dialogues we initially collected).

We then had both models interact with hundreds of virtual patients. When expert physicians blindly evaluated the resulting communications, the results were clear: the codesigned model consistently outperformed the data-tuned one across the board. It produced more comprehensive, more relevant, and more clinically useful pre-assessment communications.

The data-tuned model had learned to be brief, sometimes at the cost of being thorough. The co-designed model learned to be both efficient and effective, because that’s what the community had demanded.

A scalable mindset for global health

Our randomized controlled trial in real hospitals later proved that this co-designed AI could genuinely help, reducing consultation times by nearly 29% while simultaneously improving patients' experience of care. But the true success of PreA wasn't just in these numbers; it was in the process.

Codesign isn’t about building a single, perfect tool for one specific location. It’s about building a scalable mindset. It’s a blueprint for how to develop technology with people, not just for them. The specific health concerns in rural China may differ from those in other countries, but the principle remains the same: communities understand their own needs and constraints best.

The future of equitable AI in global health doesn't lie in simply harvesting more data. It lies in cultivating deeper partnerships. It requires us to listen, not just to collect. By building a village around our code, we can create AI that doesn’t just mirror our world, but helps us build a healthier, more equitable one.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Medicine

This journal encompasses original research ranging from new concepts in human biology and disease pathogenesis to new therapeutic modalities and drug development, to all phases of clinical work, as well as innovative technologies aimed at improving human health.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Stem cell-derived therapies

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 26, 2026

Digital Medicine for Infectious Diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Nov 09, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in