Building More Resilient Teams: A Mathematical Approach Using Hypergraphs

Published in Mathematics

The Team Formation Problem

Assigning individuals to tasks may seem straightforward, but in practice, it quickly becomes complicated. Each person has limited time and energy, and each project requires a certain amount of effort to complete. People often work on multiple projects simultaneously, and their importance can vary from one project to another. For example, an employee might lead one project while playing a supporting role in another.

We propose a method to find team configurations that remain functional even when disruptions occur. Our solution draws on a branch of mathematics that extends beyond traditional network analysis.

Beyond Simple Networks

Most people are familiar with networks, where dots (called nodes) connect to each other through lines (called edges). Social networks, for instance, show friendships as lines connecting pairs of people. However, this representation has limitations for group activities.

Consider a research paper with five co-authors. A traditional network would show ten separate connections between all possible pairs of authors, losing important information: all five people collaborated on a single project.

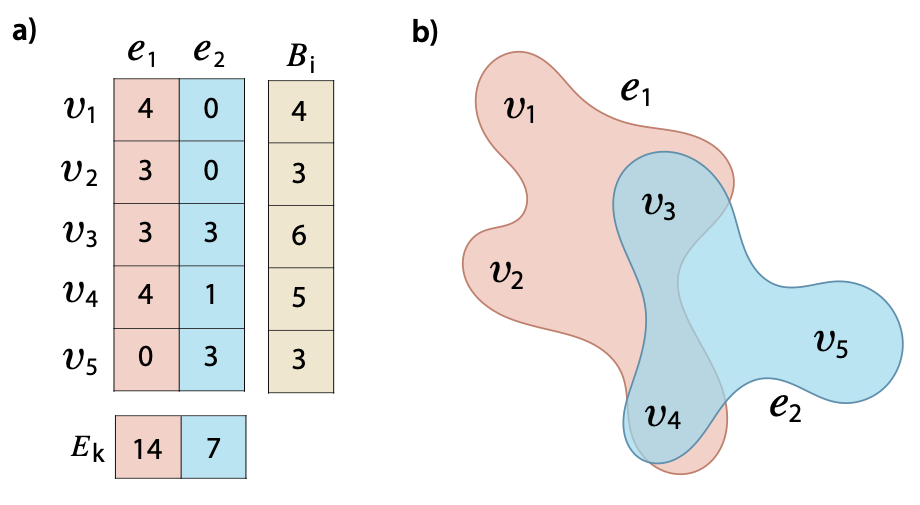

Hypergraphs address this problem (see Fig. 1). In a hypergraph, a single hyperedge can connect any number of nodes at once. For team formation, nodes represent people, and hyperedges represent projects or tasks. One hyperedge might connect three team members, another might connect seven, each representing a different collaborative effort.

We use a specific type called an edge-dependent vertex-weighted hypergraph. This allows each person to have different importance levels across different projects, reflecting how someone might contribute 40 hours to one project and 5 hours to another.

Fig. 1: Graphical representation of the team formation problem. In (a), an incidence matrix displays a task assignment problem. The rows represent nodes (e.g., people), and the columns represent hyperedges (e.g., tasks). Each entry in the matrix indicates the amount of energy, such as time, that a person can spend on a task. For example, node v4 is assigned 4 hours to task e1 and 1 hour to task e2. The sum of each row, Bi, shows the total time each person can spend on tasks, while the sum of each column, Ek, shows the total effort required to complete each task. In (b), a hypergraph depicts the same task assignment. For simplicity, the hypergraph is not annotated with time and energy constraints.

Measuring Team Resilience

The key innovation in our work is using a mathematical quantity called algebraic connectivity to measure the robustness of a team configuration. Algebraic connectivity is derived from analyzing the Laplacian matrix, which encodes the global connectivity structure of the hypergraph and governs many of its diffusive dynamics, such as heat flow, random walks, and consensus processes.

Higher algebraic connectivity indicates two beneficial properties. First, if someone leaves, the remaining team structure stays better connected, making recovery easier. Second, information flows more quickly through the organization, potentially reducing communication delays.

We impose practical constraints on our optimization: each person has a maximum budget of time or energy they can spend, and each task requires a minimum amount of effort to complete. These constraints prevent unrealistic solutions where everyone works on everything.

Finding Good Solutions

Because the number of possible team configurations grows explosively with more people and projects, finding the optimal arrangement quickly becomes computationally infeasible for almost all realistic scenarios. We use a technique called constrained simulated annealing to search for good solutions in a manner similar to the physical process of annealing: starting with initial heated configurations, then exploring and accepting possibly worse solutions during the cooling process to avoid getting stuck. Specifically, the proposed algorithm starts with a random team arrangement and gradually refines it, occasionally accepting worse configurations to avoid getting stuck in suboptimal solutions. The constraints ensure that the final result respects everyone's time limits and project requirements.

Experiments on Real Data

We evaluate our approach using two scientific collaboration datasets: publications from the American Physical Society (APS) spanning 1993 to 2021, and papers from the Microsoft Academic Graph containing "hypergraph" in their titles.

We compare our optimized hypergraphs with the original collaboration networks and hypergraphs discovered by a simpler greedy algorithm. The results show that our constrained simulated annealing approach increases algebraic connectivity by at least a factor of 10 compared to the original data.

More importantly, we test the resilience of teams by simulating the removal of team members. After removing four people and attempting to reassign their work to the remaining team members, the newly proposed and optimized configurations performed substantially better. The original collaboration networks often left tasks incomplete because the remaining team members lacked the capacity to absorb the extra work. In contrast, the optimized configurations almost always allowed complete recovery.

We also find that our hypergraph-based approach achieves similar results to a bipartite graph representation but with noticeably lower computational cost, since the hypergraph Laplacian matrix is smaller.

Practical Implications

The optimized team structures generally have more connections than the original data, meaning people work with more collaborators on average. However, the constrained simulated annealing approach limits this increase more than the greedy algorithm does, suggesting it achieves a better balance between resilience and coordination overhead.

We also note several limitations. Our current model assumes all team members are equally capable of performing any task. Future extensions will incorporate skill requirements and specializations. The approach also focuses specifically on resilience to member removal rather than other disruptions, such as budget cuts or deadline changes.

Broader Applications

While we focus on team formation, our work relates to broader questions in complex systems research. Hypergraphs appear in contexts ranging from chemical reaction networks to machine learning. The mathematical tools developed here for optimizing algebraic connectivity could be applied to designing robust supply chains, communication networks, or other systems where higher-order relationships are important.

Our code and data for reproducing these results are publicly available on GitHub, allowing other researchers to build on this foundation.

We used an AI assistant (Claude Opus 4.5) to create the first draft of this post, then edited that draft to produce the final version.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Physics

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the physical sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Physics-Informed Machine Learning

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: May 31, 2026

Advances in Quantum Networking: QKD and beyond

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in