Forecasting zoonotic disease risks in a changing climate

Published in Microbiology

This blog was originally posted on the old BugBitten site. We are resharing it now on the Research Communities site.

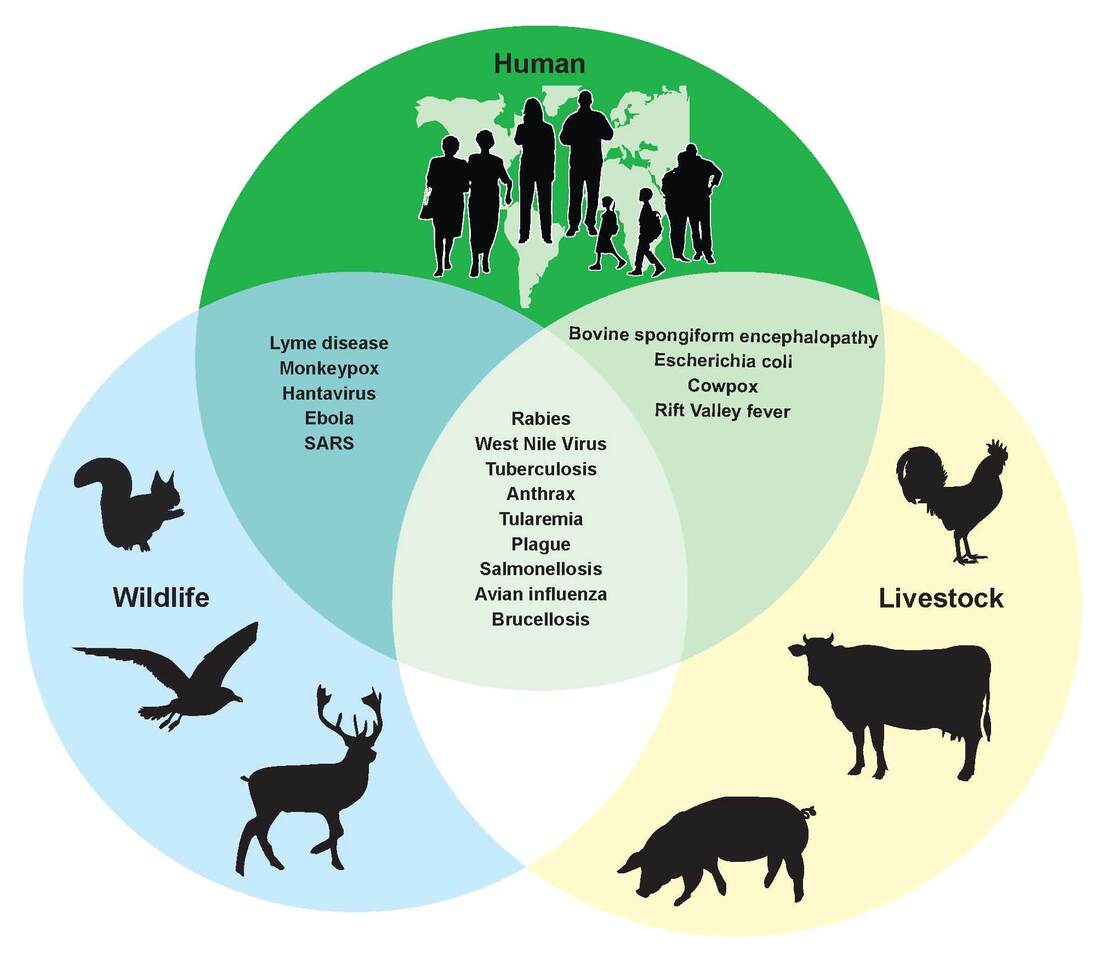

The broad impact of climate change, including sea level rise, extreme weather and biodiversity loss, extend to human health and may dramatically shift the global landscape (distriution, prevelence and incidence) of zoonotic vector-borne diseases (ZVBDs). This includes the potential emergence of new ZVBDs and increased ‘spillover’ of pathogens from animals to humans due to alterations in host and vector dynamics driven by environmental changes.

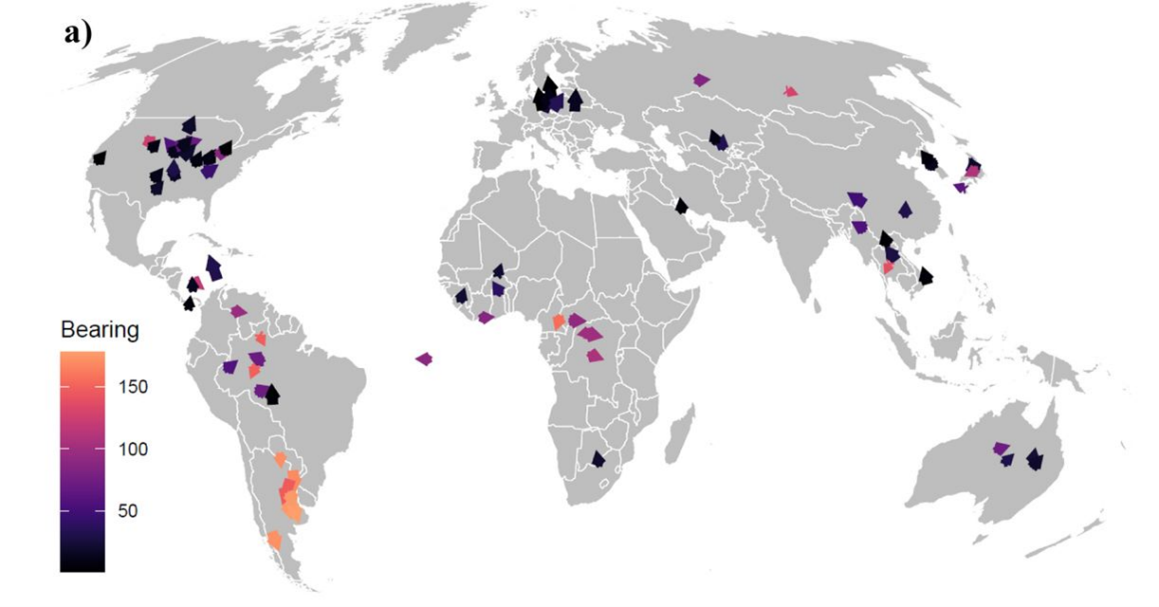

It has been predicted, for example, that host and vectors of zoonotic pathogens are likely to accumulate and come into contact at higher elevations as temperatures warm, in biodiversity hotspots and areas with high human population density, resulting in increased risk of virus transmission between host species (whether humans or animals).

Building resilience against these changing ZVBD landscapes is crucial, particularly in regions with limited socio-economic development and historically underdeveloped healthcare infrastructure. Public health agencies must therefore proactively enhance their capacity to detect, respond to, and manage ZVBDs as they arise in new environments.

As some key ZVBDs already appear to be on the rise in some regions (e.g. Aedes-borne viruses), there's a need to forecast and predict how ZVBDs might further disseminate, as well as understand the connection between human disease risk and global environmental changes. However, these links are generally poorly understood, despite climate change and ZVBDs both representing independent threats to humanity.

Modelling the impact of climate change on zoonotic vector-borne diseases

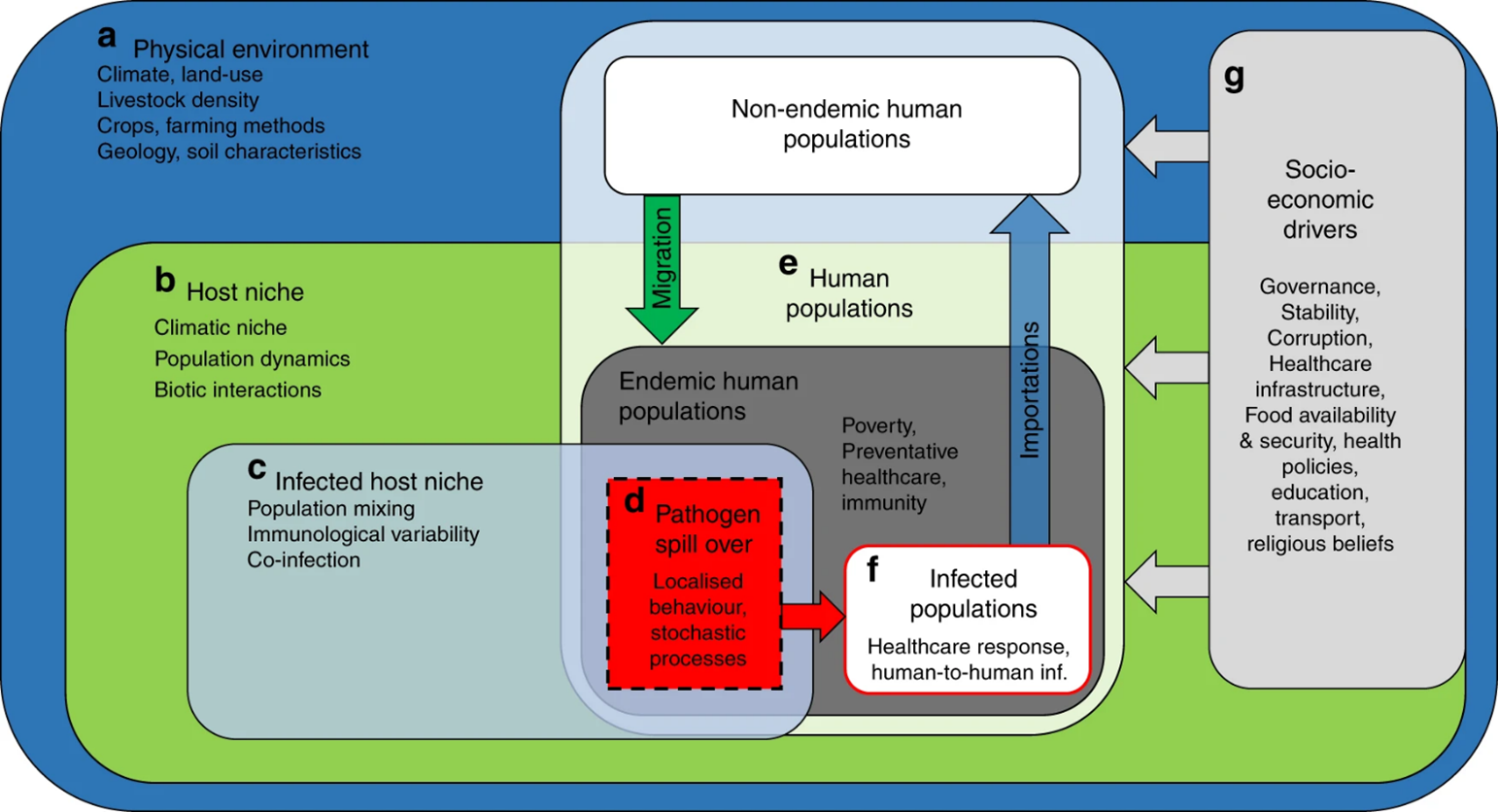

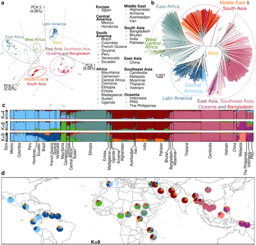

To investigate the links between ZVBD distribution, spillover risk to humans, and an altering environment due to climate change, a preprint from researchers at the Natural History Museum (London) and University College London (UCL) applied a combined ecgological-epidemological approach to develop models to predict how suitable environments are for both host and vector of 165 ZVBDs, including 114 viruses, 18 bacteria, 30 endoparasites, and 3 fungi. Across all ZVBDs, the geographic ranges of 1058 hosts and vectors were incorporated into their model.

Using reported data on host, vector, and pathogen distributions globally, researchers predicted the endemic range of each pathogen geographically. They combined this with 15 climate scenarios from the present to 2080 to forecast the risk of human exposure to different ZVBDs under varying warming levels. Using this approach the researchers could then project the possible impact of climate-driven environmental changes on the spread and movement of those ZVBDs, identifying regions at higher risk of emergence considering socioeconomic factors.

Changes to zoonotic vector-borne disease endemic areas

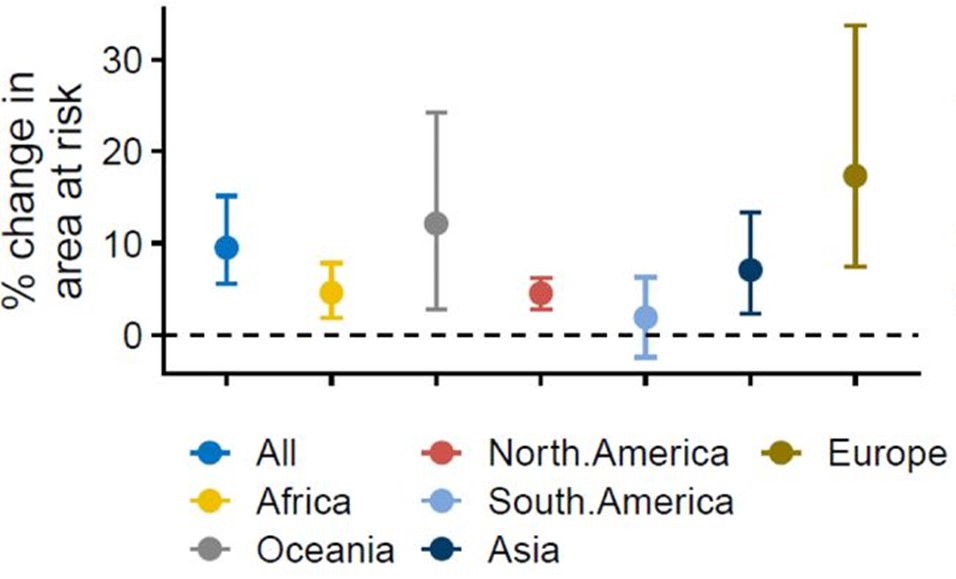

Of the 165 zoonotic vector-borne diseases in the study, the modelled endemic ranges of 141 matched their current known ranges. Of those, 101 were clinically confirmed to infect humans and were used for further modelling and analysis. Under a ‘medium’ climate change scenario (RCP = 4.5) projected until 2050, the model showed a 9.6% mean increase in the endemic areas across all 101 zVBDs, with similar patterns of range expansion found on all continents.

When projected until 2080, over half of the zVBDs (54.5%) had predicted expansions in their endemic ranges due to climate change, whilst 18.1% had smaller ranges, and 27.4% remained roughly similar in range.

The model showed that zVBDs with more complex transmission routes, such as those involving multiple host and vector species (e.g. Lyme’s disease and plague), often had smaller endemic ranges by 2080 compared to those zVBDs with simpler, vector-only transmission cycles (e.g. Dengue). This suggests heightened vulnerability to climate-induced ecological disruptions, which may potentially separate host/vector species necessary for complex transmission routes, thus limiting their endemic areas and transmission.

Under a ‘medium’ climate change scenario (RCP = 4.5) projected until 2050, the model showed a 9.6% mean increase in the endemic areas across all 101 ZVBDs, with similar patterns of range expansion found on all continents.

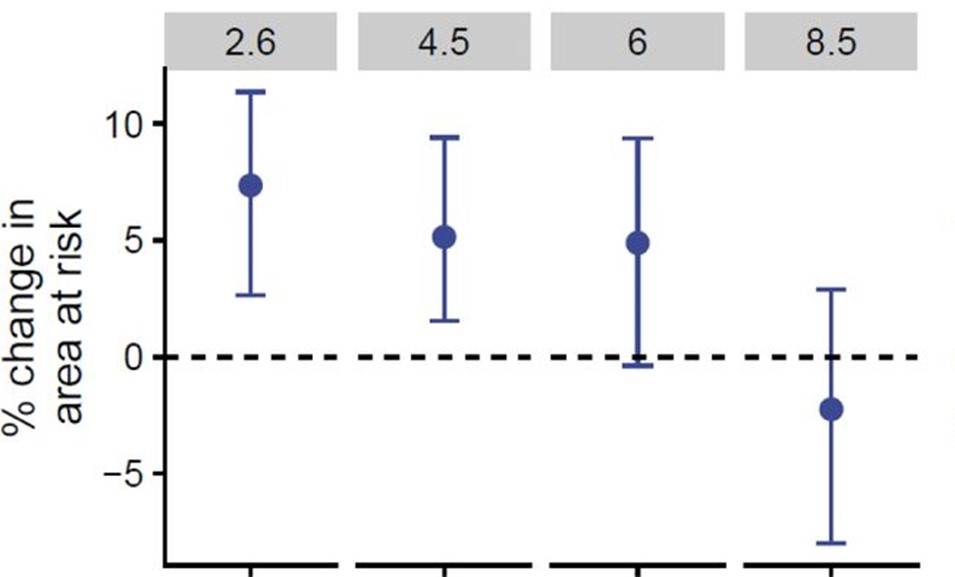

Interestingly, the percentage change in endemic area by 2080 was actually found to become weaker and revert as warming increased beyond 2 °C, supporting other predictions of changes to cross-species viral transmission risk due to climate change. This impact of more severe warming is noted to possibly result in a decrease in the ability of animal hosts and vectors to disperse fast enough to ‘keep up’ with movement of their environmental niches, and is consistent with the considerable loss in biodiversity expected as climate change becomes more pronounced.

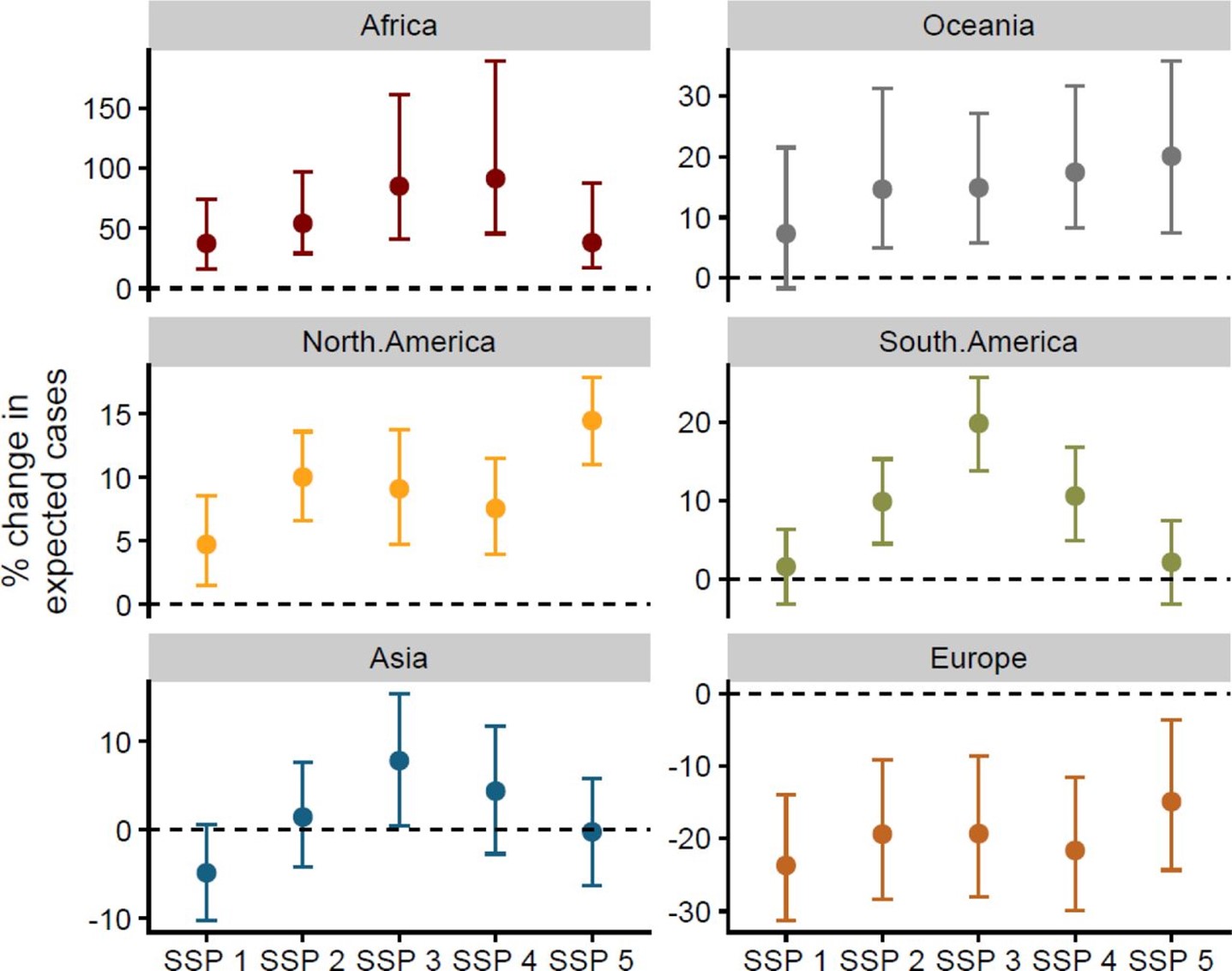

Lastly, the researchers assessed how changes to the expected burden (i.e. number of cases) of ZVBDs across each continent changed under five socioeconomic development scenarios (Shared Socio-economic Pathways (SSPs)), assuming that increased poverty will result in more severe disease outcomes and higher incidence. The model revealed substantial variation in disease burden among continents. Except for Europe, all continents were generally projected to experience a greater disease burden under all five (SSP) scenarios. Africa showed the largest increases (25-75%), followed by Oceania and the Americas (5-20%).

Conclusion

By using the known geographical ranges of hosts, vectors, and ZVBDs, alongside climate change projections, the authors developed mathematical models to forecast the broad-scale implications of climate, economics, and sociodemographic changes on ZVBD distribution and risk globally.

Overall, the study suggests ZVBD endemic areas will shift and expand, increasing risk to human populations, especially in regions heavily impacted by climate change and have rapid population growth. As ZVBDs spread, there is a strong possibility they will reach immunologically-naive (i.e. previously unexposed) human populations, heightening the risk of severe disease manifestations and larger outbreaks.

This research underscores the importance of understanding climate-induced changes in pathogen distribution, offering insights into potential outcomes under different warming scenarios and emphasizing the urgent need to address climate change as a significant threat to human (and animal) health globally.

Follow the Topic

-

BugBitten

A blog for the parasitology and vector biology community.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in