A Hidden Epidemic: Female Genital Schistosomiasis and HIV co-moribidty

Published in Microbiology and Public Health

Among these challenges to women's health, Female genital schistosomiasis (FGS), stands as a particularly devastating and severely under recognised condition affecting millions of women worldwide.

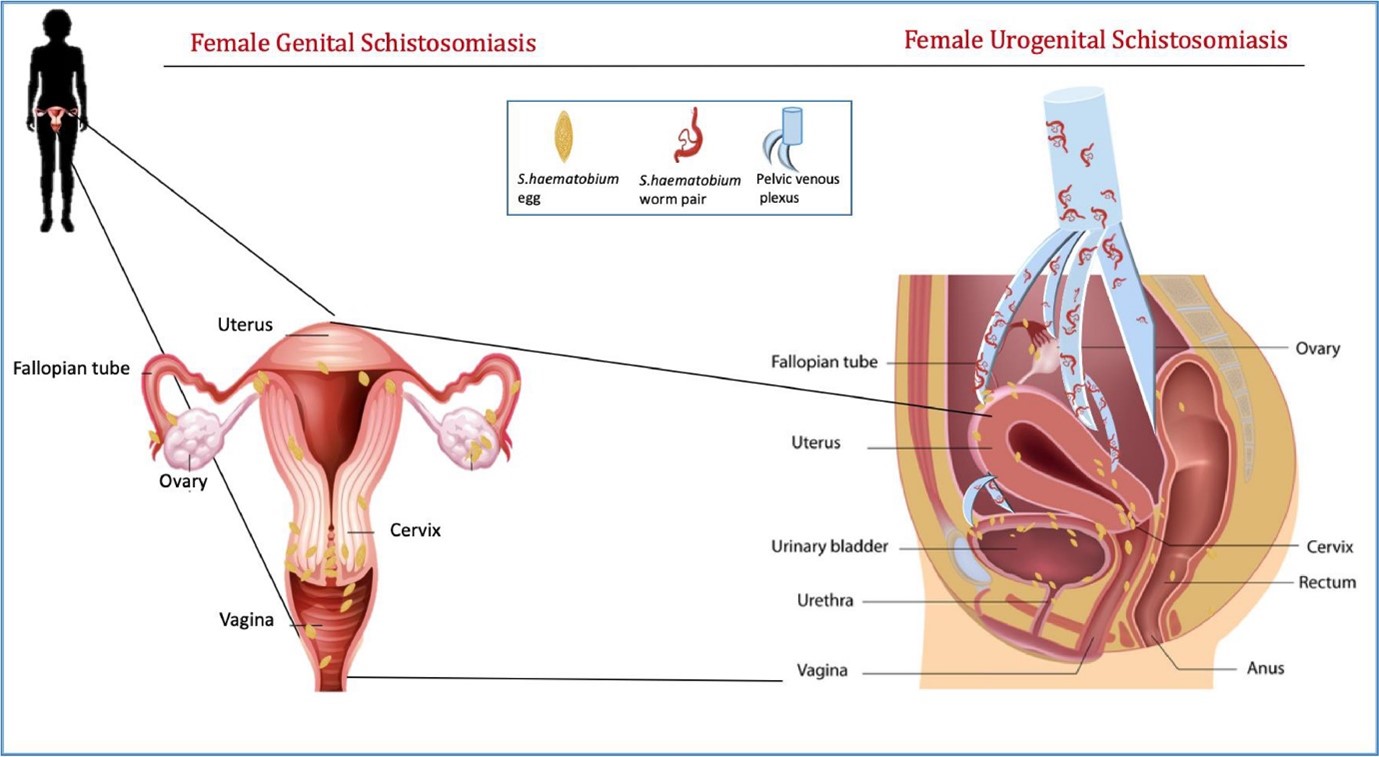

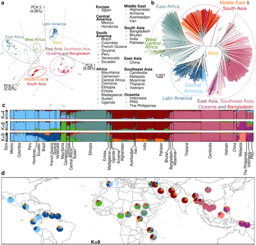

Schistosomiasis is a neglected tropical disease caused by infection with parasitic trematodes of the Schistosoma genus. More than 200 million people globally are infected, the vast majority of which are in low-resource areas of the Global South. Female genital schistosomiasis is a gynaecological health condition Schistosoma haematobium. The infection occurs when women come into direct contact with water bodies infested with S. haematobium larvae, which emerge from specific aquatic snail hosts. These parasitic larvae can penetrate human skin upon contact with contaminated water during everyday activities like washing clothes, bathing, or collecting water. The geographic range of S. haematobium, including Sub-Saharan Africa, parts of the Middle East, and Corsica, is limited by the range of these aquatic snail hosts.

Approximately 56 million women are estimated to be affected by FGS, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa. It is thought around 70% of women with urogenital schistosomiasis infections will develop FGS, yet the condition is chronically underdiagnosed due to widespread misconceptions, stigmatisation, and limited awareness even among healthcare providers.

Sufferers of FGS experience non-specific symptoms including vaginal pain, discharge, contact bleeding, and pain during sex, which are often misconstrued for the symptoms of sexually transmitted infection (STI). Additionally, FGS can cause lesions on the cervix that make the sufferer more vulnerable to STI contraction.

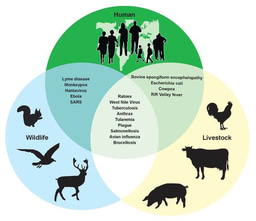

FGS has established relationships with STIs, the most well-studied of those being with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). This virus infects immune cells including CD4+ T cells and macrophages, leaving the sufferer vulnerable to other pathogens. When left untreated, HIV will develop into acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), which can be fatal if left untreated.

Sub-Saharan Africa has some of the highest HIV prevalence in the world, with 67% of the global population of people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa.

FGS and HIV interaction

A correlation between FGS and HIV has been observed in Zambia, Mozambique, and the Republic of Tanzania. In the Zambian study, schistosomiasis was linked to higher HIV acquisition in women. However, the relationship is not simple- in the Tanzanian study, women were found to have three times greater incidence of HIV infection, even if they were infected with the intestinal Schistosoma mansoni.

The mechanism behind the relationship between FGS and HIV requires further study, but two mechanisms have been highlighted. Firstly, there are an increased number of HIV-receptor cells in women with FGS cervical lesions- those being the cells HIV uses to enter the body. Secondly, the contact bleeding during sexual intercourse common in

women with FGS increases the risk of HIV transmission.

Current interventions

However, as global recognition of FGS increases, and a holistic, multifaceted approach to healthcare is further encouraged, steps are already being taken to address both FGS and HIV, and their co-morbidity.

Efforts to educate healthcare workers on FGS, including the creation of the ‘FGS Pocket Atlas, and ensuring girls have access to safe water and toilets at school, aim to reduce the burden of FGS in sub-Saharan Africa. Combining interventions, such as providing HIV testing services and schistosomiasis test-and-treat services at the same facilities, would contribute towards the control and treatment of both conditions.

As research advances on diagnostic tools for FGS and HIV detection, as well as other STIs with FGS co-morbidity such as human papillomavirus (HPV), there is growing hope for integrated screening approaches that can simultaneously address these interconnected conditions. By continuing to build awareness and develop holistic interventions, we move closer to breaking the cycle of these silent epidemics affecting women's health globally.

Follow the Topic

-

BugBitten

A blog for the parasitology and vector biology community.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in