From the BugBitten Archives: A new potential way of tracking malaria incubation periods in mosquitos

Published in Microbiology and Biomedical Research

This blog was originally posted on the old BugBitten WordPress site. We are resharing it now on the Research Communities site.

In many developing countries, malaria is a leading cause of disease and death. Via transmission through mosquitos, the responsible Plasmodium parasites have infected and impacted countless lives throughout history, prompting the writer John Whitfield to write in 2002, “Malaria may have killed half of all the people that ever lived.” And according to the World Health Organization, there were approximately 249 million cases of malaria and about 608,000 deaths from the disease across over 80 countries in 2022.

So, advancing research on the disease is therefore of the highest priority.

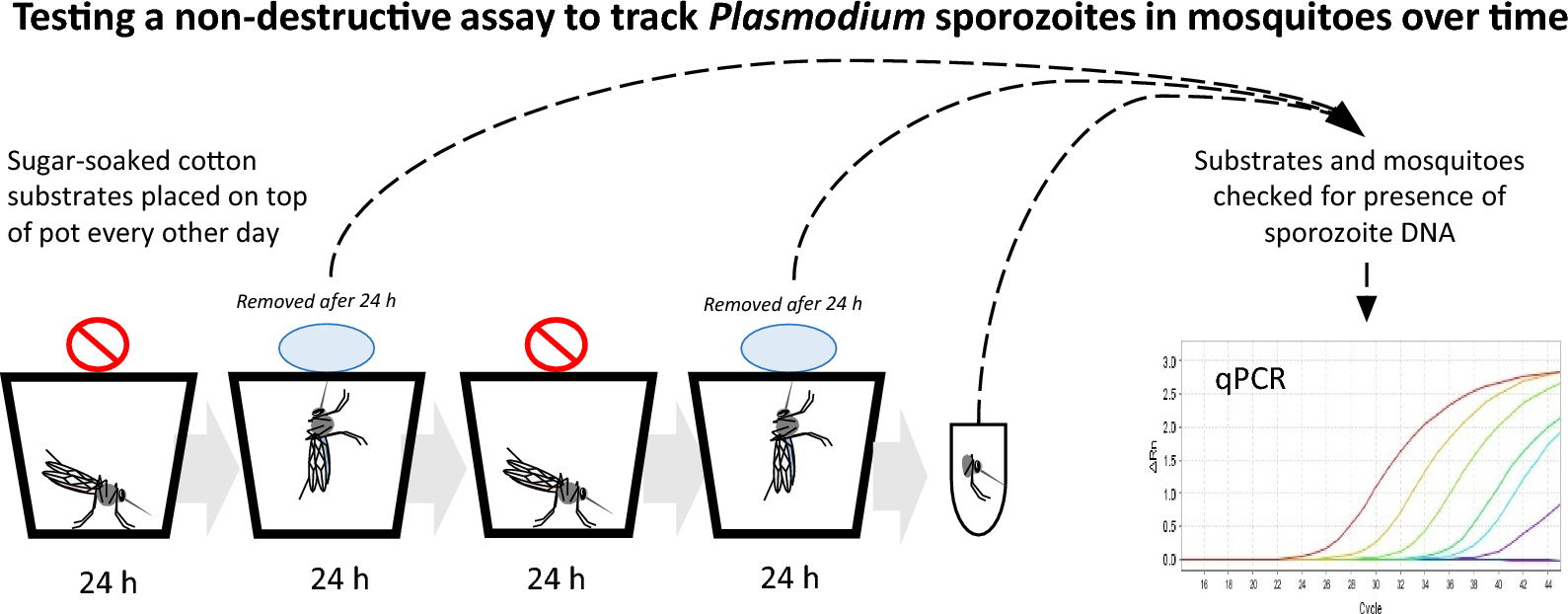

This week’s blog takes a look at one of the most important parameters for studying malaria: the extrinsic incubation period (or EIP). In a research article recently published in Parasites & Vectors entitled “Testing a non-destructive assay to track Plasmodium sporozoites in mosquitoes over time”, Oke et al. report a more efficient way of tracking this criterion.

Firstly, some background information. The EIP is the amount of time required for the disease-causing parasite to turn infectious, which usually occurs after ten to twenty days. However, the reasons for variation in the EIP are not well understood, in part because scientists can only test a host mosquito once. Researchers typically sample them from a population and either bisect them or dissect their salivary glands, whereupon they assay the sporozoites. There are some drawbacks here. For example, these methods are quite laborious, and as each mosquito can be tested only once, it is impossible to track individuals and their levels over time; instead, the EIP is typically approximated from the mosquito population as a whole.

However, sporozoites are also left behind during sugar feedings, so it could be possible to use a non-destructive assay to evaluate levels in one mosquito multiple times and potentially better measure the EIP.

Oke et al. used a feeding substrate soaked in sugar to collect the sporozoites. Mosquitoes were starved for 24 hours before being provided with the substrate, at which point they were allowed to feed for 24 hours. The substrates were then taken away for testing before the process was repeated once more, so that there were two substrates per mosquito. Oke et al. specifically studied sporozoites from two types of robent malaria, P. berghei and P. chabaudi, as the two don’t share the same EIP, and used a quantitative-PCR assay.

So, what did they find?

Well, after analysis, Oke et al. did find sporozoites, just as they predicted. However, they found fewer than expected. Of the 24 sugar-soaked substrates used on the P. berghei-infected mosquitoes, only seven (29%) were found to be positive, and of the 18 substrates from the P. chabaudi-infected mosquitoes, that number was three (17%). They played around and adjusted their methods, for example, using groups of four mosquitoes, but their detection rate did not go up and they wondered if the sporozoites were left behind on the substrate at a fluctuating rate.

However, this low rate could also potentially be explained by the biology of the sporozoites, the behavior of the mosquitoes when feeding, or perhaps a mix of the two.

So, further studies are needed to reveal the root of the low detection rate, but this study by Oke et al. shows an important step forward in tracking individual mosquitoes rather than populations when studying EIPs, which could in turn have a large impact on malaria research as a whole.

Poster image credit: PitiyaO / Getty Images / iStock

Follow the Topic

-

Parasites & Vectors

This journal publishes articles on the biology of parasites, parasitic diseases, intermediate hosts, vectors and vector-borne pathogens.

-

BugBitten

A blog for the parasitology and vector biology community.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Credelio Quattro

Articles published in the collection have already gone through the systematic peer review process of the journal.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 24, 2026

Translational leishmaniasis

Topics of interest include:

• Analytical and omics-based advances for parasite detection, monitoring, and characterization.

• Comparative biology of Leishmania and related parasites, with emphasis on shared mechanisms of infection and survival.

• Host-pathogen interactions and immune responses.

• Epidemiology and transmission dynamics, including drawing parallels between leishmaniasis and other parasitic infections.

• Translational strategies in drug discovery, vaccine development, and therapeutic interventions applicable to leishmaniasis and related parasitic diseases.

By linking leishmaniasis with other parasitic diseases of similar characteristics, this collection seeks to foster integrative approaches, stimulate cross-disciplinary dialogue, and accelerate the translation of knowledge into innovative diagnostic, preventive, and therapeutic solutions.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 01, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in