How Do Heavy Metals Move Through Hard-Rock Aquifers? New Insights from Multi-Layered Column Experiments

Published in Earth & Environment and Civil Engineering

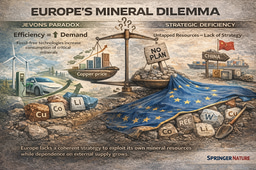

Groundwater contamination by heavy metals remains one of the most persistent environmental challenges worldwide. While soft sediment aquifers have been widely studied, far less is understood about how contaminants behave in hard-rock aquifer systems—which dominate large parts of India and many regions globally.

In our recent study published in Environmental Science and Pollution Research, we explored how two contrasting contaminants—cadmium (Cd²⁺) and chromate (CrO₄²⁻)—interact with different hard-rock environments under realistic subsurface conditions.

What did we do?

We designed laboratory systems that mimic natural aquifers using both:

-

Monolithic columns (single rock/mineral type), and

-

Multi-layered columns representing real geological sequences such as:

-

Basalt–Serpentine–Bentonite

-

Limestone–Calcite–Shale

-

Granite–Feldspar–Kaolinite

-

This allowed us to examine how contaminants actually travel through layered subsurface formations rather than idealized single materials.

Key Findings

✔ Mineralogy matters: Carbonate-rich and serpentine materials showed exceptionally high retention of cadmium (up to ~5800 mg/kg), mainly through ion exchange and structural incorporation.

✔ Charge controls behavior: Cr(VI) (anionic) and Cd(II) (cationic) behaved very differently. Chromate retention depended largely on surface charge, while cadmium was strongly governed by ion-exchange processes.

✔ Layering changes everything: Multi-layered systems did not behave as simple averages of their individual components. Water chemistry evolved as it passed through successive layers, dramatically altering contaminant mobility.

✔ Granitic systems were least reactive, suggesting higher vulnerability to heavy-metal transport compared to basaltic and limestone aquifers.

Why This Matters

Hard-rock aquifers supply drinking water to millions, yet their contaminant attenuation capacity is poorly constrained. Our work highlights that realistic multi-layer geochemistry must be considered when predicting groundwater risk and designing remediation strategies.

Understanding these processes can help environmental scientists and policymakers better assess where natural geological barriers can protect groundwater—and where additional intervention is urgently needed.

We hope this study sparks further discussion on incorporating true subsurface complexity into contaminant transport models.

Read the full article to explore the experiments and findings in detail.

Follow the Topic

-

Environmental Science and Pollution Research

This journal serves the international community in all broad areas of environmental science and related subjects with emphasis on chemical compounds.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in