Know Culture; Nudge Better

Published in Social Sciences, Business & Management, and Economics

Explore the Research

23727322251408076?int.sj-abstract.similar-articles.2?utm_campaign=related_content&utm_source=HEALTH&utm_medium=communities

For about 20 years, the nudge movement been finding ways to change people's behavior, but a new analysis is updating that idea. The new results suggest that whether nudges are the most cost-efficient tool for behavior change depends on which culture you're in.

The promise of nudges is clear. People aren't saving enough for retirement? Make contributions the default. Employees aren't mixing enough? Put in fewer coffee machines so people bump into each other in the break room. Nudges have become so influential that governments like the UK started their own "nudge units."

But then there was pushback. One critique was that nudges are paternalistic. But another critique focused on their effectiveness. The idea is that nudges don't work as well as a simple method--paying people.

Nudges vs. Money Put to The Test

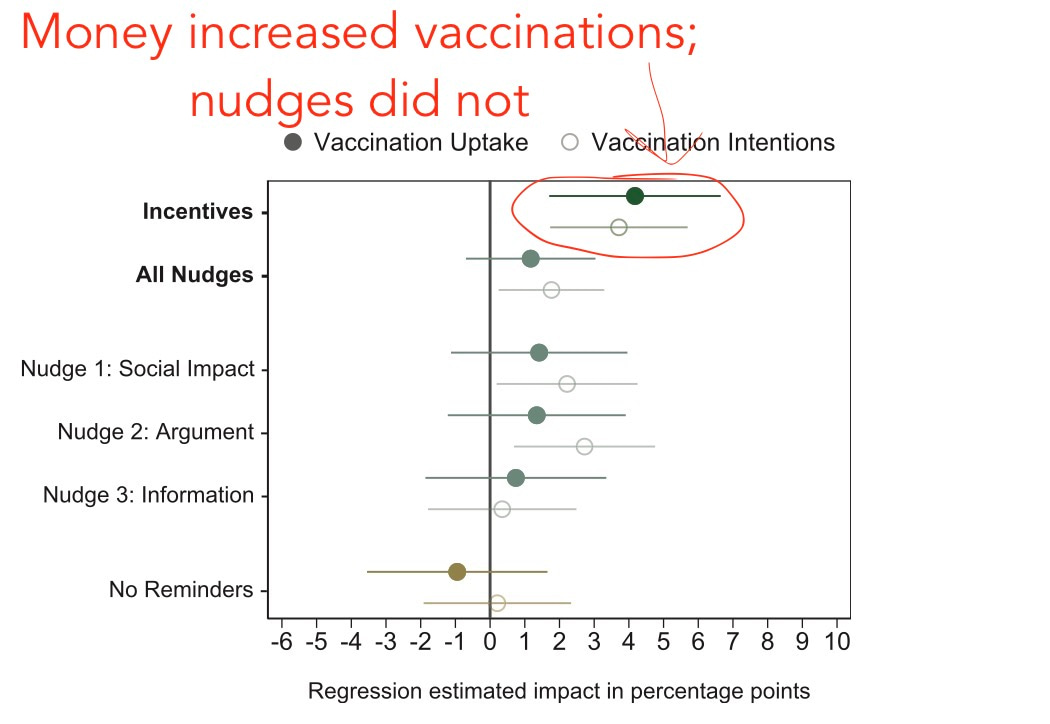

Several mega-studies have put nudges to the test against paying people. For example, one study tried to get convince people to get the Covid vaccine. Some people got nudges, like information about the vaccine or a small request for participants to list other people that would benefit if the participant got vaccinated. Other people got money--about $24--if they got vaccinated.

In the end, the money won. The nudges didn't increase vaccination rates, but the money did.

In the end, the money won. The nudges didn't increase vaccination rates, but the money did.

Another study tried to get people to go to the gym more often. Nudges did actually boost gym attendance. For example, researchers sent people text message reminders or asked people to think about the values behind why they want to go to the gym.

But those nudges were inferior to money. And it didn't take much. Even paying people as little as about 25 cents was enough to outperform the nudges.

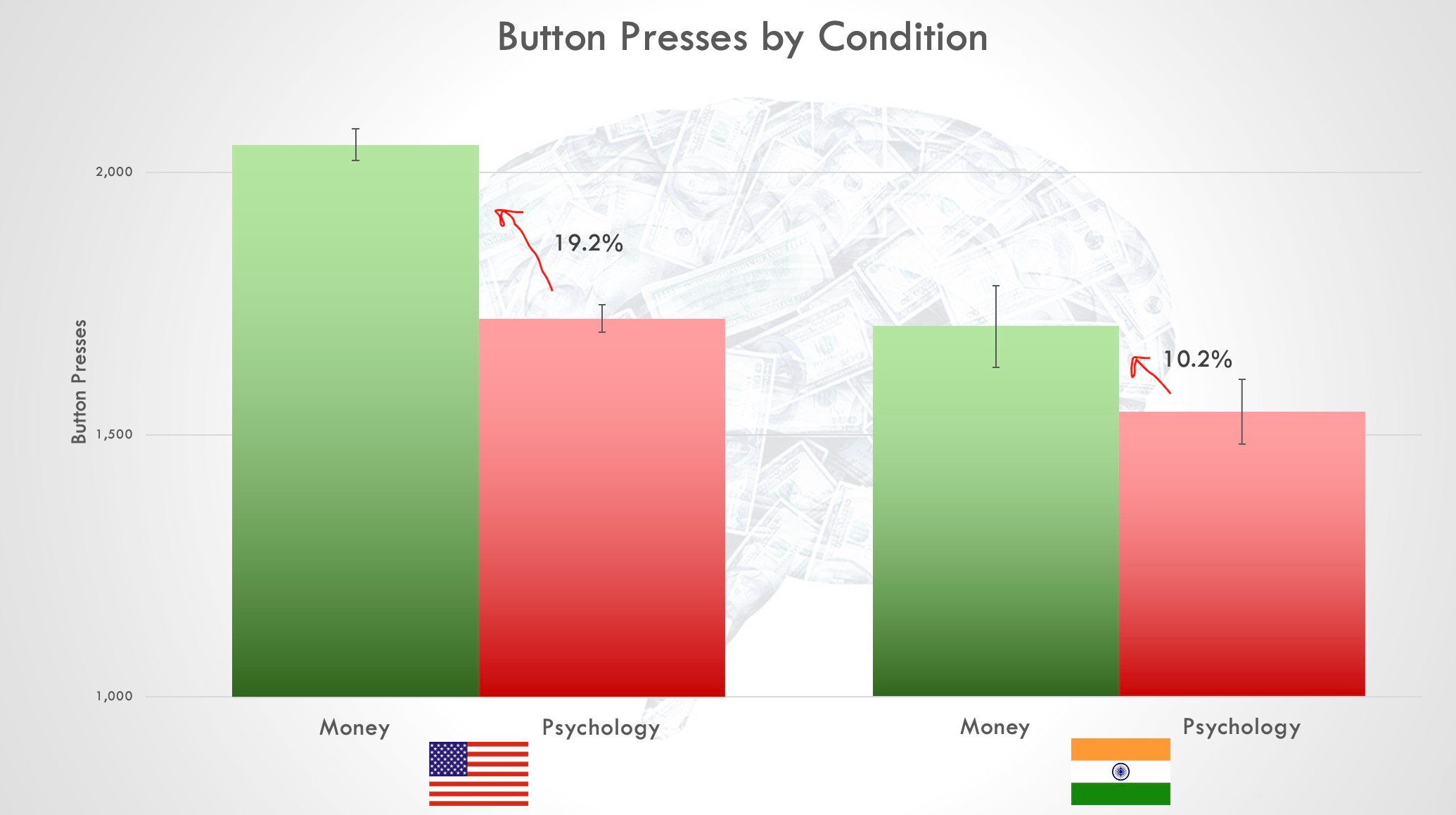

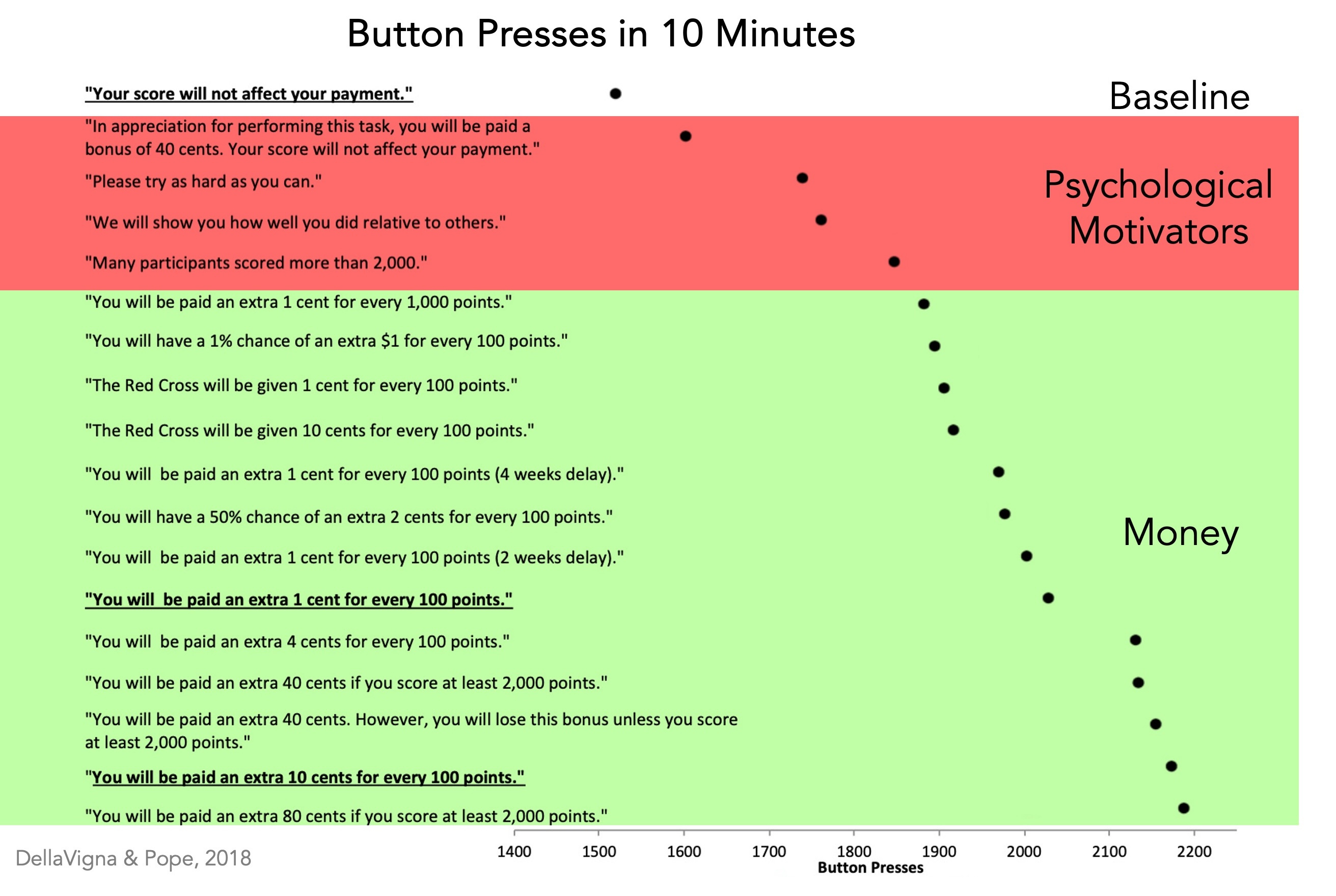

Results were similar in a study of workers on an online platform run by Amazon. Researchers asked workers to do a simple--perhaps stupid--work task. Workers pushed the "A" and "B" buttons on their keyboard for 10 minutes.

Researchers gave some workers nudges, like communicating a social norm by saying how hard other people tended to work. Another nudge was simple--the researchers just asked nicely, "Please try." Again, these nudges worked, but the best nudge was less effective than the worst amount of money.

One Factor All The Mega Studies Missed

The conclusion seems strong. The studies are in different domains. They use large samples. And they test a wide range of payments and nudges. These are all strengths.

But the studies had one limitation in common. They were all done in Western cultures--mostly the US.

That's a problem for our science. It's a problem because research has found people are more likely to think studies of Americans reveal truths about human psychology, but studies outside the US reveal truths about culture. It's as if America has no culture.

It's also a problem because people are using behavioral interventions to improve people's lives outside the US. Governments and NGOs are trying to encourage people to use mosquito nets, take the TB vaccine, and plant drought-resistant crops. It would be unwise to use results from American gym-goers to design seed programs with farmers in Malawi.

New Hints in Old Data

That led my colleagues and me to wonder whether the conclusions from those mega studies would be the same outside the West. Fortunately, one of the mega studies had data from a second culture hidden in plain sight. The mega study on Amazon's work platform has mostly workers from the US, but it also has a portion of workers in India. Bingo!

My research team re-analyzed their data, separating out workers in the US and India. When we did, we found the story differed a bit across cultures. In the US, money outperformed nudges by 19%. In India, it was closer to 10%. We called this percentage "the money advantage."

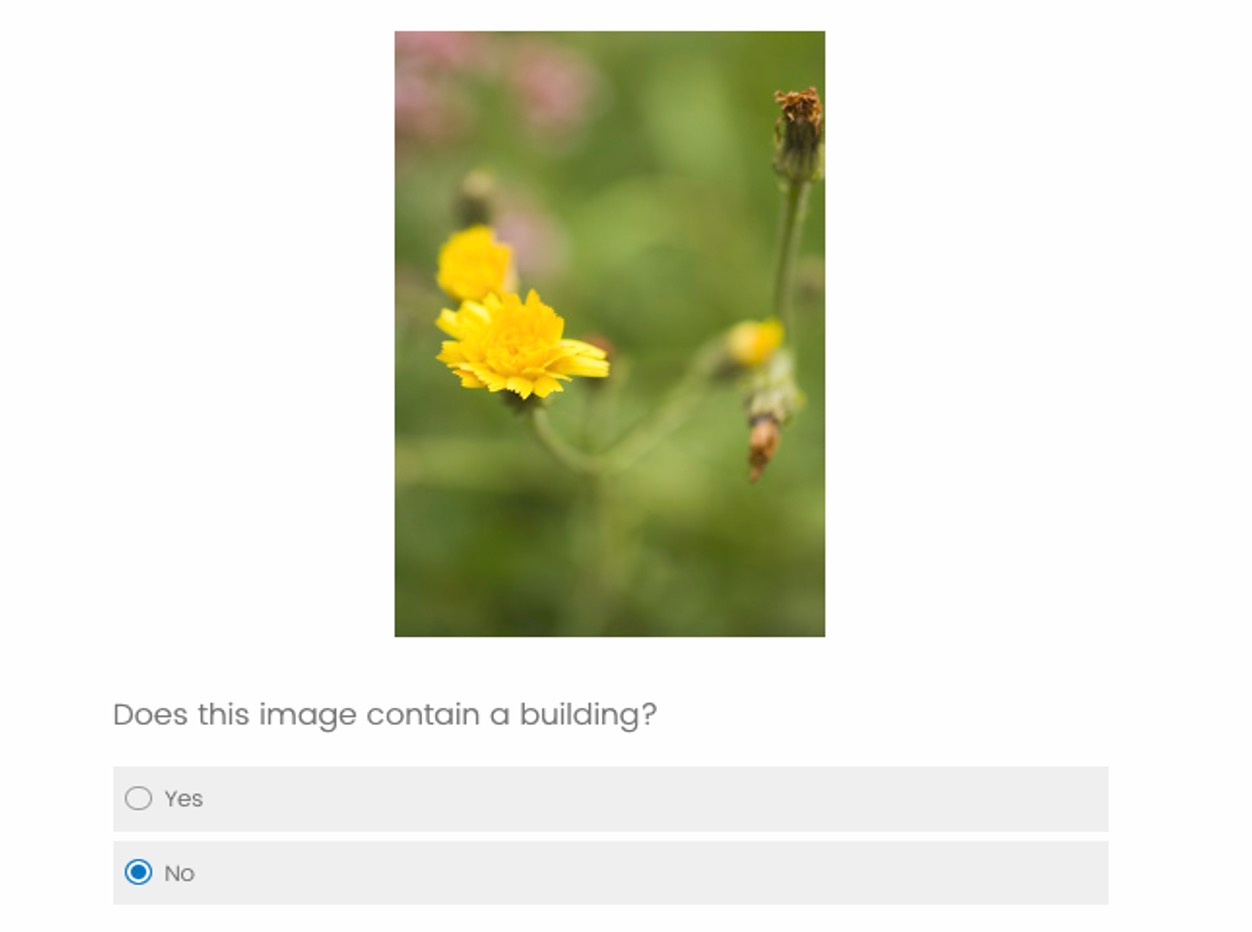

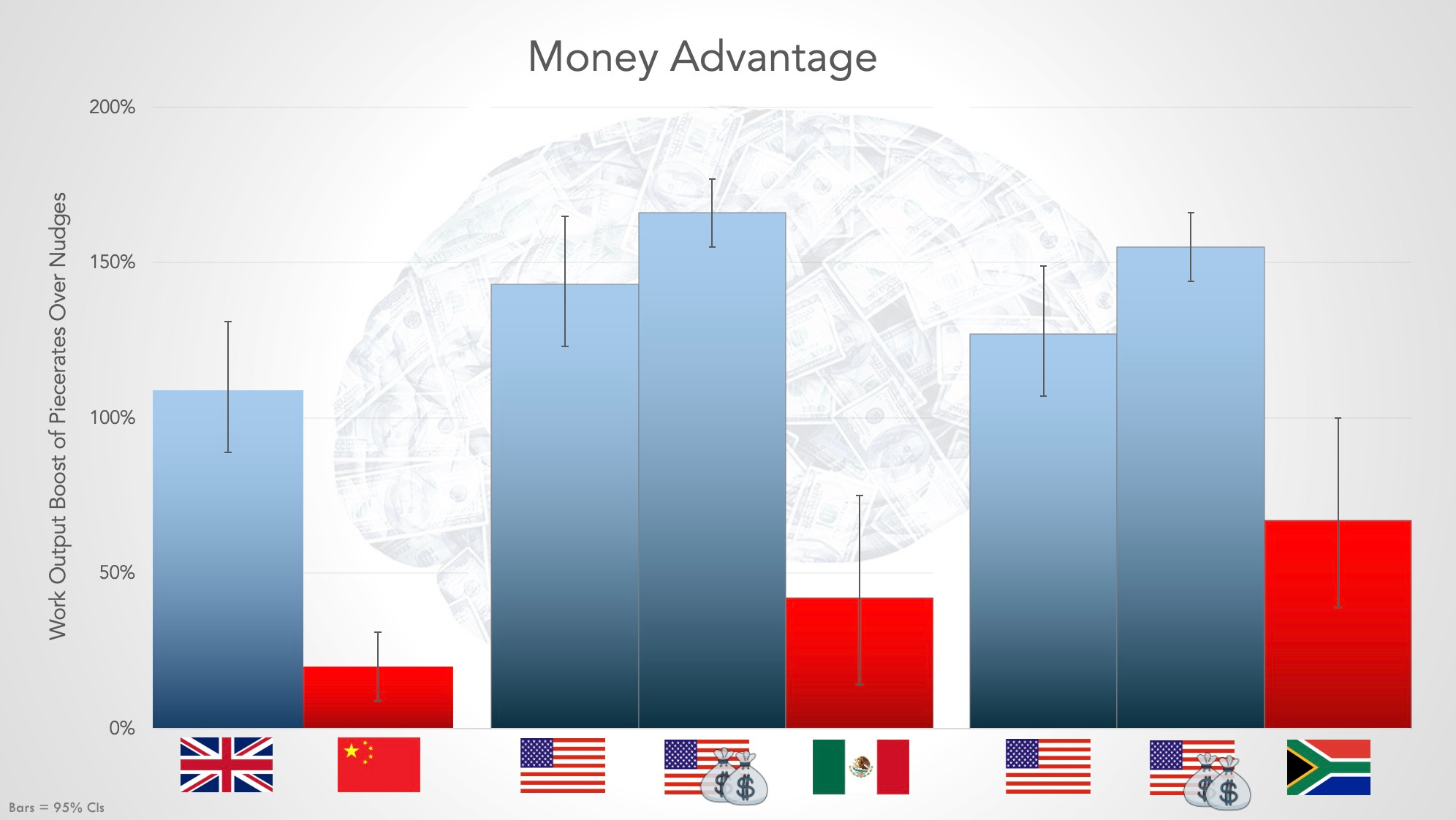

My research team followed up by running new tests of the money advantage in the US, UK, China, Mexico, and South Africa. Participants completed an image-classification task that worked like CAPTCHA questions, which you have probably completed to prove you're human.

We gave some people nudges, like a social norm or a competition framing. We gave other people small performance incentives, like an extra 5 cents for every 10 images completed. In the US and UK, money outperformed nudges by over 100%. Outside the US and UK, it was about half that.

One explanation is that nudges like social norms are more powerful outside of individualistic cultures. In cultures like the US and UK, people may be less persuaded by following other people's example or polite requests from the researchers. But these might hold more sway outside of Western cultures.

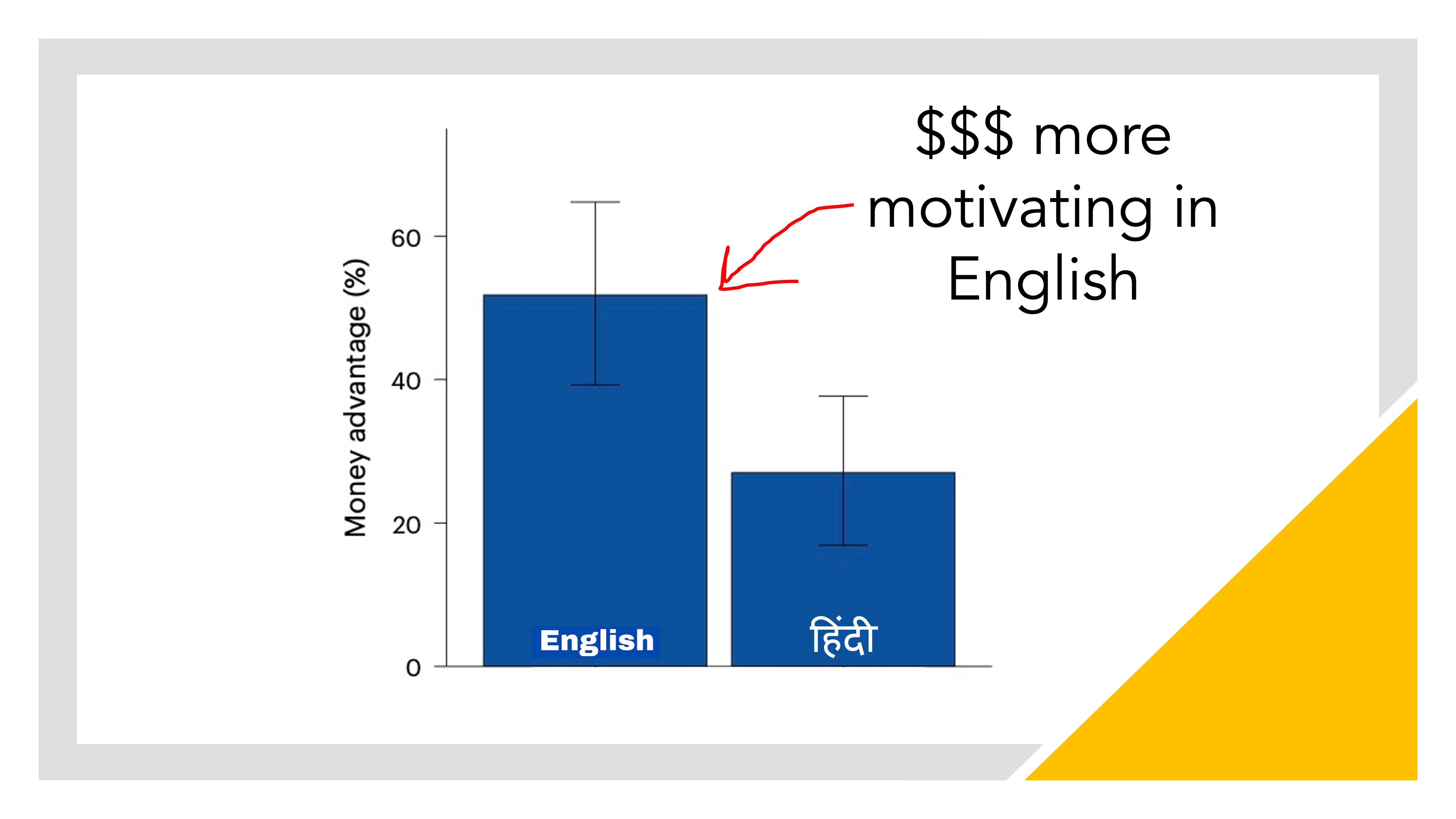

In one study, we found that simply changing the language of the work task was enough to shift the power of money. We randomly assigned about 2,000 people in India to take the study in English or Hindi. The money advantage was about twice as strong in English than in Hindi.

And what's more, the language seemed to change how people thought of what they were doing in the first place. When the study was in English, participants were more likely to agree with the statement, "I only completed the study for money." In English, participants thought of it more like a market exchange.

Know Culture; Nudge Better

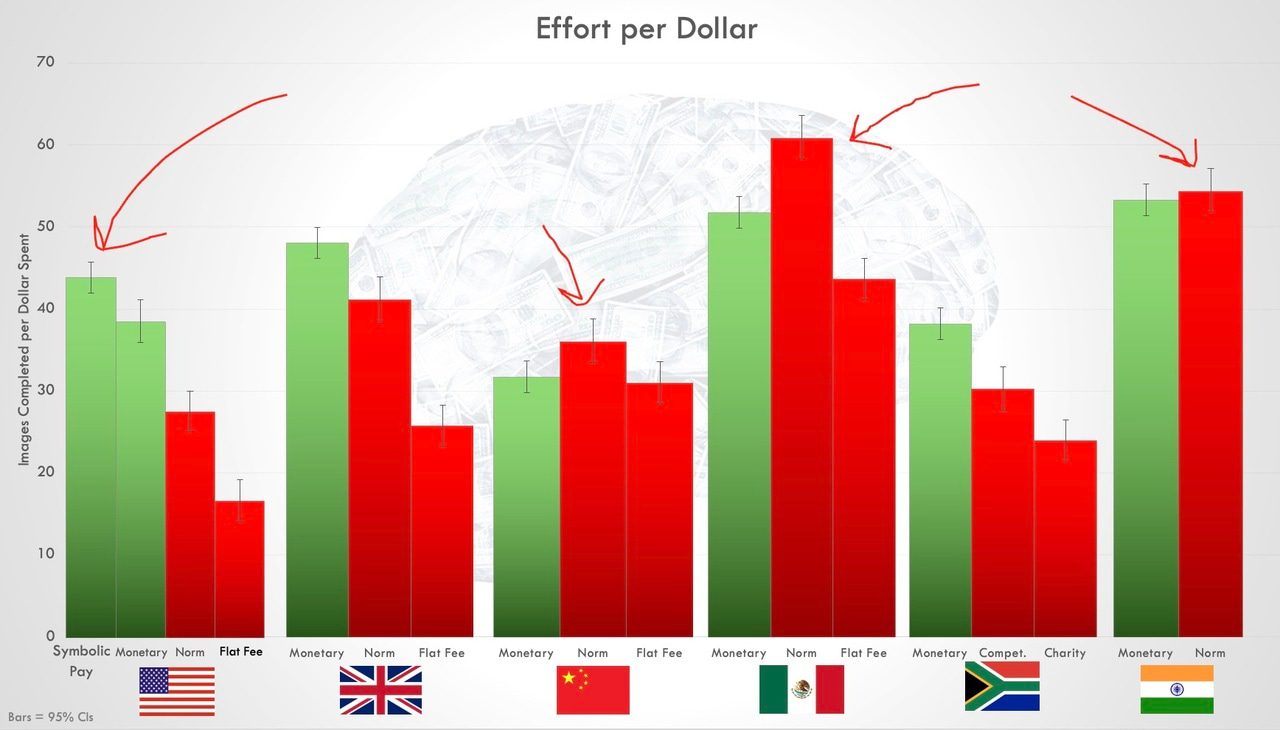

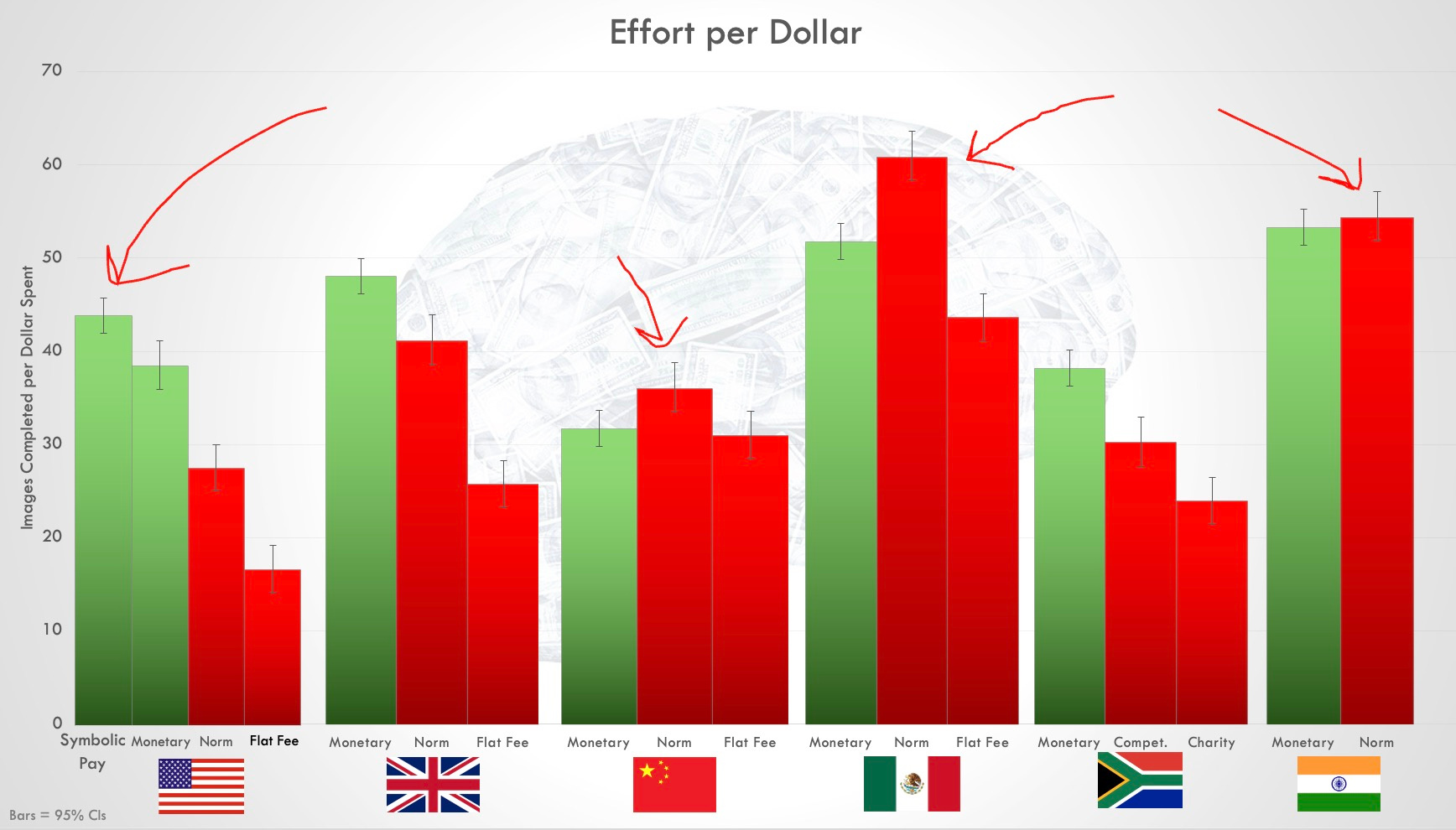

With all of this data across cultures, we were able to calculate the cost-effectiveness of money versus nudges across cultures. Per dollar spent, how much images did we get completed?

In the US, UK, and South Africa, paying people money was the most cost-effective. Yes, paying people performance incentives cost us money, but the boost in output was so big that it outweighed the extra cost.

But in China and Mexico, the social norm was more cost-effective. And in India, it was a tie.

Similar to the gym study, the money didn't have to be good. In one study, we tested the effectiveness of what we called "irrational pay" (or perhaps more diplomatically, "symbolic pay"). In this condition, people received incentive pay, but it was very low. The original incentive was 5 cents for 10 images, and we lowered it to 1 cent for 20 images. This new incentive bonus was so low that workers would be better off quitting our task as soon as they got their base pay, after which they could start a different task on the platform.

Our participants in India mostly ignored this low bonus pay. But our participants in the US worked harder with the irrational pay. And when we looked across all conditions, this irrational pay condition was the most cost-efficient of all.

Of course, these studies bring up thorny ethical questions. Reasonable people might conclude irrational pay is not ethical, especially at work. Others might argue that our results lead to the conclusion that pay should be lower in non-Western cultures. We are not arguing that.

What we are arguing is that interventions to create social good--like vaccinations, mosquito netting, or recycling--might be able to create more good if they understand culture. In some places, paying a smaller number of people might create the most good. In some places, reaching a larger number of people with a nudge like a social norm might create the most good. But before we can make better decisions about how to use scarce resources to make the world a better place, we need to know culture.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in