Neglecting future urban development and changing risks can lead to maladaptation to natural hazards

Published in Sustainability

In our pursuit to adapt to unavoidable climate change and natural hazards, we are in danger of making things worse for ourselves if we do not figure out how to avoid “maladaptation”. Yes, we must still act. But I’m arguing that we ensure we do so intelligently.

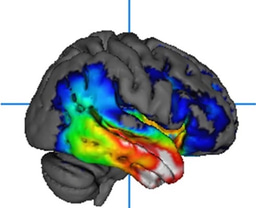

My paper, “Hard-adaptive measures can increase vulnerability to storm surge and tsunami hazards over time”, was published on Friday in Nature Sustainability. It makes two contributions: 1) We quantitatively show that existing adaptation approaches, such as building seawalls to protect from tsunami, can increase vulnerability; 2) In doing so, we demonstrate that neglecting dynamic feedbacks, such as urban development changes and changing risks, can substantially alter the assessment of whether strategies are effective or not.

For example, consider a classic example of a flood risk assessment. The flood hydraulic model captures how fluid moves and we can change the amount of fluid. Build a levee or river bank and the fluid will move differently, thus changing the risk map. The result is that development and investment occurs in these now “safe” areas. The issue is that this increased activity increases our risk to wall failure or extreme events. Essentially, making our communities potentially more vulnerable than before, when they were aware of the hazard.

Two things need to happen:

- Practitioners and researchers need to be aware of the possibility that by not including dynamic feedback, there risk assessments may be significantly wrong. I’m not convinced that they are aware even of the concept of maladaptation.

- The community needs to understand that engineering adaptations have limitations and when they choose where to live, they may still have risks. For example, 55% of the US population lives in counties protected by levees.

Although we demonstrate this in the case of tsunamis, the notion may be generalizable to other spatial and repeatable hazards such as flooding, wild fires, and storm surge. By modifying areas that are naturally at risk from these events so that people think it is safe to live there, we simply encourage that development and jeopardize people’s lives and livelihoods. It is perhaps better to modify where we live, rather than repeatedly try to force the natural environment to behave as we’d like.

The paper was funded by the National Science Foundation, the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science, the University of Michigan, and the Technical University of Delft’s Delta Infrastructure and Mobility Initiative.

This post is also published on my blog, Reckoning Risk.

Journal reference:

Tom M. Logan, Seth D. Guikema, Jeremy D. Bricker. Hard-adaptive measures can increase vulnerability to storm surge and tsunami hazards over time. Nature Sustainability, 2018; DOI: 10.1038/s41893-018-0137-6

Follow the Topic

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcementLatest Content

Why is Singapore Identified in Global Research as Number One? How Physical Activity and Education Excellence Created a Global Leader

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in