One Health Day One Year on: Mpox and H5N1 Avian Influenza

Published in Immunology

In 2021, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), World Health Organization (WHO), and the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) came together to form the ‘Quadripartite Collaboration for One Health’.

One Health is ‘an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals and ecosystems’. It recognises the interconnectedness of humans, animals, and the environment and mobilises multiple sectors to work together to tackle all aspects of disease control including detection, preparedness, prevention, response and management. One Health Day is celebrated each year on the 3rd of November and aims to highlight the importance of utilising a One Health approach to tackle global health challenges. One Health spans across several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), but in the context of SDG 3 it relates specifically to targets 3.3, 3.8 and 3.d.

|

|

|

Last year I wrote a blog for One Health Day, focusing on what at the time were some of the most pressing health threats that needed a One Health approach to help solve them. These included emerging infectious diseases like bird flu and Mpox along with the increased threat of antimicrobial resistance, these (along with the Covid 19 pandemic) highlighted the need to strengthen the health workforce's emergency preparedness. Mpox and H5N1 became prevalent in the lead up to One Health Day last year. Now, one year (and one month) on, I am looking back at these infectious diseases to see what major developments have occurred and what progress has been made in that timeframe.

Monkeypox

On the 5th of September this year WHO announced that Mpox was no longer a public health emergency (after declaring it as such in August 2024) after sustained declines were seen across countries like the DRC, Sierra Leone and Uganda, which previously had the highest cases. A 52% reduction in cases in July and August compared to April and May was seen, due to groups across Africa coming together to strengthen local workforce capacity, work on laboratory-capacity building, surveillance and infection control. For example, in the DRC, the number of testing sites increased from 9 to 28 since August 2024. However, funding constraints and competing health emergencies have meant that the vaccine response to the outbreak has fallen short of what was needed, with 2 million vaccine doses still yet to reach those who need protection. Unfortunately, mpox hotspots have since emerged in new countries like Ghana and Liberia, and countries outside of Africa are also detecting variant clade Ib including Malaysia, the Netherlands, Spain and Portugal.

At the end of August, WHO held the 5th meeting of the Emergency Committee regarding the upsurge of mpox 2024. The risk of many aspects of the disease, e.g. growth rate and incidence, transmission risk, and severity have decreased in the last year, however the risk associated with ‘response capacity and access to countermeasures’ has not changed. WHO has suggested a strategic transition of Mpox control from an emergency response to sustained health system-integrated efforts. This transition would include stockpiling vaccines for regional spikes and integrating Mpox prevention within other platforms e.g., HIV, which could help to prevent future outbreaks at the scale of that seen in 2024. Efforts have been made to help control and prevent Mpox transmission over the last year, however we are not out of the woods yet, and these efforts must be maintained and the situation monitored.

H5N1 Avian influenza

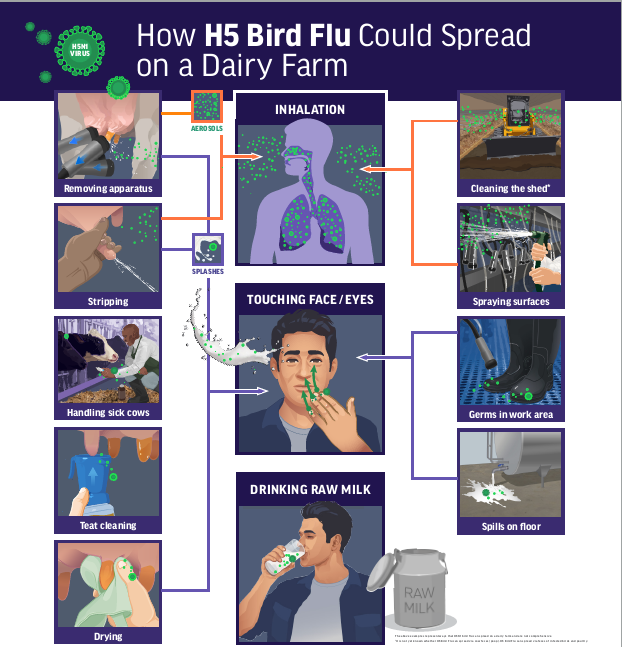

Bird Flu is ‘back’ and it’s ‘everywhere’… This time last year we were seeing H5N1, which rarely infects mammals, beginning to spread rapidly in cattle the US. At the same time, two possible human cases had been detected but not yet confirmed. I noted last year that despite the Covid-19 pandemic showing the importance of detecting, reporting and responding to disease outbreaks to prevent them becoming pandemics, One Health strategies were still being underutilised, and early detection methods and strategies to prevent zoological spillover were lacking. One year on and the CDC have now reported 71 confirmed cases of bird flu in humans in the US, mainly due to exposure to dairy herds and poultry farms. As the name suggests, the main symptoms are those of the flu, but interestingly the predominant symptom has been eye redness and conjunctivitis. Cases have mainly been mild, but there is the possibility of severe illness, underpinning the importance of containing the virus and controlling its spread. Cases in poultry decreased in the summer but since September the virus has killed nearly 7 million farmed birds, likely impacted by the migration of wild birds south for the winter.

Although the CDC has declared the public health risk associated with the virus low, H5N1 is causing devastation to farm animals across the US, with the government shutdown suspending communication of vital up-to-date guidance. As of 7th November, 26 cases were reported across farms here in the UK, and so farmers were mandated to keep chickens in barns in the hopes of preventing a repeat of the 2021-2023 epidemic (and what we are seeing presently in the US). Positively, this same week, it was reported that immunologist Runhong Zhou and colleagues have developed an antibody for H5N1. The antibody targets the virus stem and hosts receptors, a strategy that was shown to enhance antibody efficacy. Meanwhile, another team from Columbia University are tracking how the H5N1 virus evolves and are hoping to identify potential treatments to multiple strains. Research in this area is vital to prevent avian influenza spreading uncontrollably.

Although there is currently no known person-to-person spread of H5N1, infection in humans working in close contact with cattle and poultry, and infection in wild birds and farmed animals is a prime example of the interconnectedness of animal, human and environmental health. We need to utilise a One Health approach to engage multiple sectors and encourage the sharing of data, in order to control H5N1 spread through farm and wild animals, and prevent the possibility that the virus evolves a person-to-person transmission strategy.

One Health lessons from the last year

The health of humans, animals and ecosystems are closely interlinked and changes in the relationships between these, like increased proximity to animals, or climate change, can increase the risk of new or reoccurring infectious diseases spreading in humans and animals. . One year on from the zoonotic disease Mpox being declared a public health emergency, the number of people yet to receive vaccinations remains high and the disease has spread to new countries both in and out of Africa, however collaboration on surveillance and prevention has meant that cases have decreased since 2025. Meanwhile H5N1 cases in humans have increased and are surging again in birds, and research on the evolution of the virus and potential treatments is ongoing. We must take a more holistic approach to monitoring, recording, and managing diseases to curb the spread Mpox and H5N1, and to prevent zoonotic spillover and strengthen the global response to potential future pandemics.

Follow the Topic

Ask the Editor - Immunology, Pathogenesis, Inflammation and Innate Immunity

Got a question for the editor about the complement system in health and disease? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in