People Aren’t Stupid: They’re Wary of False Information About COVID-19

Published in General & Internal Medicine and Arts & Humanities

In 2021, I traveled to six West African countries to conduct a study on COVID-19 perceptions and lead training sessions on public awareness. COVID-19 vaccination, which began in March or April depending on the country, was a clear failure—very few people were showing up to get vaccinated. Since February 2020, the WHO had been repeating that an “infodemic” of false information about COVID-19 was “just as dangerous” as the pandemic itself, in the words of its Director-General. This infodemic was often said to explain the low vaccine uptake.

However, the discussions I had and the interviews I conducted did not suggest that people were particularly distrustful of COVID-19 vaccines. A large portion of the population didn’t see themselves at risk from COVID-19. Many believed it was a “white people’s disease” and thought Africans were protected either by the climate or by some kind of natural immunity. Misinformation about vaccines didn’t seem to play a role in the low uptake, even though African countries had the lowest vaccination coverage in the world.

In 2023, I conducted a study on COVID-19 vaccination in Niger, where only 22% of the population was vaccinated. The study confirmed my previous observations (https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.23-0708). A high 73.3% of the population believed that COVID-19 vaccines were “a good thing,” and 83% of those who had heard vaccine promotion messages supported them. This clearly showed that, at least in Niger, low vaccine uptake wasn’t due to mistrust of vaccines.

Since 2021, it had also become clear that the alarmist narratives and articles from 2020 predicting that a wave of misinformation would prevent adequate vaccine coverage had been wrong. In industrialized countries, people rushed to get vaccinated as soon as the vaccines became available. The pessimistic forecasts proved completely off base.

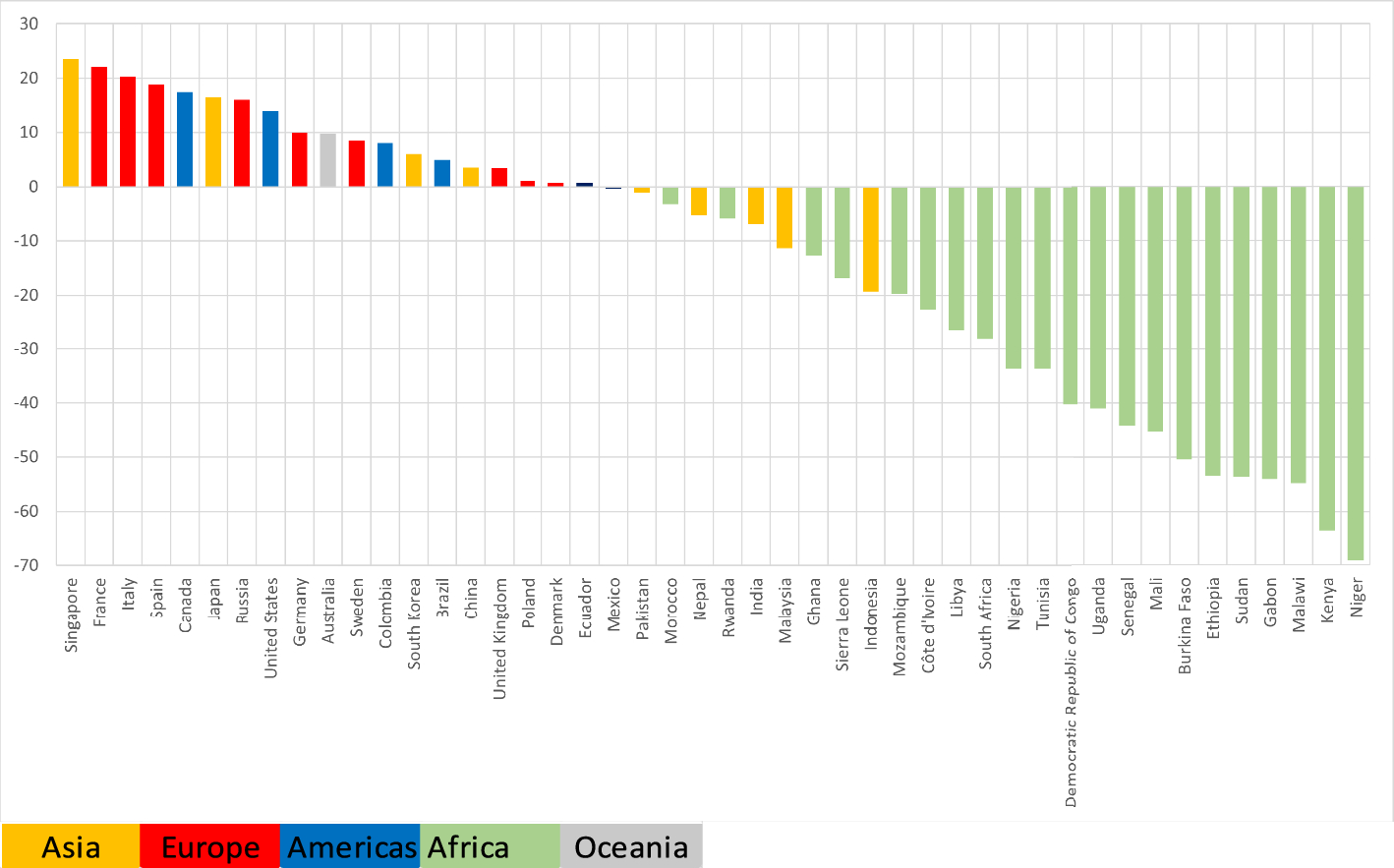

That led me to compare the intention to get vaccinated expressed in 2020 with actual uptake, and to evaluate whether exposure to false information had influenced the gap between intent and uptake. In other words, to see if misinformation had dissuaded some people from getting vaccinated. The results of this study, conducted in 46 countries and published in Discover Public Health, were unequivocal: there is no connection between exposure to misinformation online or on social media and the difference between stated vaccination intentions and actual uptake.

The internet and social media carry far more accurate health information than false information. Studies have shown that, contrary to popular belief, this is even more true for COVID-19 than for other health topics. You’d have to hold the public in pretty low regard to believe they’re more influenced by false information than by accurate information.

Follow the Topic

-

Discover Public Health

This is an open access journal publishing research from all fields relevant to public health.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Public Health Strategies for the Management and Prevention of Tobacco Use and Emerging Tobacco Products

Tobacco use is considered as one of the hidden epidemics of the 21st century. Despite many efforts at policy level, tobacco use still remain one of the key factors for high morbidity and mortality worldwide. Globally around eight million people die due to tobacco consumption while daily people are diagnosed with lung cancer, COPD, cardiovascular diseases etc., with main factor being the tobacco consumption. Tobacco prevalence range between and within regions and countries as well as between male and female gender. Tobacco uses usually starts at adolescent and continue in the later life. At global level several initiatives have been undertaken with the WHO-FCTC being one of the most important. Additionally, at national levels countries have undertaken several initiatives but with not very successful results. On the other hand, tobacco industry is putting priority in the new products such as electronic cigarettes, heated tobacco etc. These products are not considered in many regions and countries as the normal tobacco products with their taxation, availability and use being different. To some extent, healthcare systems are not performing well in the management of the tobacco use which is considered a chronic condition. Availability of new medicaments and approaches and techniques is still a problem in many settings worldwide. Combination of tobacco use and other substances is also a critical issue.

This Collection aims to discuss key strategies for management of tobacco use and the new products at local, national, regional and global level as well as to propose key measures for healthcare personnel and policymakers in order to manage key challenges. Authors from different settings and different backgrounds are invited to submit their works to this Collection. Reviews and systematic analyses and meta- analyses, original articles, policy papers and case-studies are more than welcome to be submitted.

Research areas may include but are not limited to the following:

- Tobacco consumptions

- New tobacco products

- Prevention and management of tobacco use

- Substance use

- Technology and public health

- Prevention and health promotion

Keywords: tobacco, heated tobacco, public health, health policy, prevention and health promotion

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 3.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Antimicrobial Resistance: The New Challenge to Global Health in a Post-Pandemic World

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a seriously ongoing threat to global health, occurring when bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites evolve to resist the drugs designed to kill or block them. The COVID-19 pandemic has both directly and indirectly exacerbated the problem of AMR, as the overuse of antibiotics has accelerated the development of resistance in many pathogens. COVID-19 may have subsided, but AMR continues to pose a significant risk to the effectiveness of global healthcare systems, threatening to reverse decades of progress in combating infectious diseases. The interplay between population health and AMR has become increasingly critical as healthcare practices have shifted in response to the pandemic. Understanding this relationship is essential for developing effective strategies to mitigate the impact of AMR on population health in a post-COVID context.

The motivation for launching this Collection arises from the urgent need to address the rising tide of AMR as healthcare systems grapple with the long-term effects of the pandemic. Increased antibiotic use during COVID-19 treatment, changes in healthcare access, and disruptions in public health interventions have all contributed to an environment where AMR can thrive. Moreover, the pandemic has highlighted the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to tackling AMR, involving epidemiology, policymaking, and community health initiatives. This Collection aims to provide a platform for researchers and practitioners to share insights and findings that can inform future strategies to combat AMR while considering the broader implications for population health.

This Collection aims to highlight the multifaceted nature of AMR in a post-pandemic environment. We solicit articles that investigate the particular issues provided by the pandemic in terms of AMR development and containment, examine the impact of AMR on many sectors of healthcare, and propose novel strategies to minimize resistance propagation. Submissions may include original research, policy assessments, program evaluations, and comments on the following major areas:

• Epidemiology and trends of AMR post-pandemic

• Impact of COVID-19 on antibiotic usage

• Surveillance strategies for AMR

• AMR and stewardship

• Prevention and control measures to limit AMR spread

• Policies and programs to promote antibiotic stewardship

• Economic and social implications of AMR

• Global collaboration and initiatives to tackle AMR

By addressing these critical issues, this Collection aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the emerging challenges in antimicrobial resistance in a post-pandemic world and to promote effective strategies to preserve the power of our current antimicrobials.

Keywords: antimicrobial resistance; COVID-19; antibiotics; global health; infectious diseases; public health; policy; prevention

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 3.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in