Why we explored Cas3 for ATTR: A different kind of CRISPR for safer gene disruption

Published in Pharmacy & Pharmacology

ATTR (transthyretin amyloidosis) is a progressive disease caused by misfolded transthyretin (TTR) protein. Over time, TTR can deposit in tissues—especially the heart—leading to serious organ dysfunction. Because most circulating TTR is produced in the liver, ATTR has become an important target for therapies that lower hepatic TTR production.

CRISPR-based gene editing has recently gained major attention in this space. Cas9-based liver editing for ATTR has already shown impressive clinical momentum, highlighting the potential of a durable, one-time intervention. At the same time, therapeutic gene disruption raises a practical question: after editing, what kinds of gene products might remain? In a protein misfolding disease, even low-level, unexpected TTR variants could be undesirable.

That question led us to explore an alternative CRISPR system—CRISPR–Cas3—as a deletion-based approach for robust gene disruption. Cas3 works very differently from the “molecular scissors” image often associated with CRISPR. Cas3 functions with a multi-protein Cascade complex and can create directional deletions, removing a segment of DNA rather than introducing a small local change. From a therapeutic standpoint, this deletion-based mechanism is appealing: it may provide more reliable gene knockout, reducing the likelihood that partially functional alleles remain.

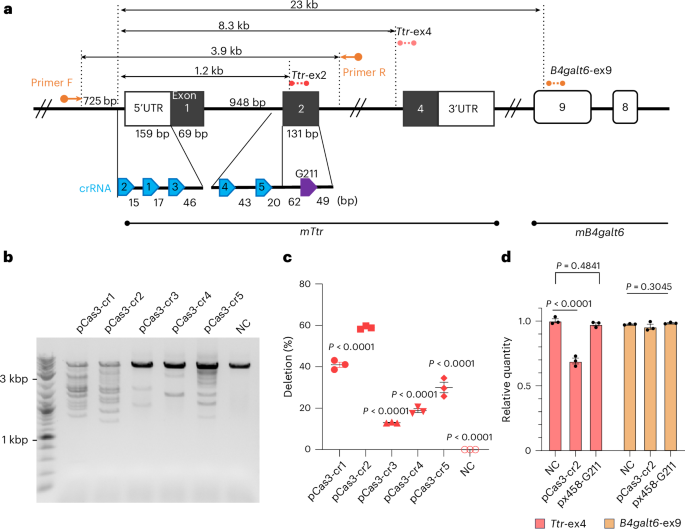

To test whether Cas3 could be developed into a practical therapeutic strategy, we tackled three key challenges: efficiency, delivery, and protein-level outcomes. First, we optimized Cas3 editing in liver-derived mouse cells. After screening guide RNAs, we identified an active crRNA that produced robust on-target editing at the Ttr locus. We then characterized the DNA outcomes and observed Cas3-like deletion patterns. We also performed extensive assessments for unintended editing using targeted capture sequencing and whole-genome approaches, and did not detect reproducible off-target mutations under our experimental conditions.

Second, we asked whether a multi-component Cas3 system could be delivered efficiently in vivo. Therapeutic genome editing depends heavily on delivery, and the liver is well suited for systemic delivery using lipid nanoparticles (LNPs). Importantly, LNP delivery of mRNA provides transient expression of the editing machinery—an attractive feature for therapeutic development.

We therefore delivered the Cas3 components as modified mRNAs together with a stabilized guide RNA, packaged into LNPs and administered intravenously. A single dose achieved substantial liver editing and produced a marked reduction in circulating TTR. This was a major milestone: it demonstrated that even a complex, multi-component CRISPR system can be delivered using clinically proven mRNA–LNP technology and can achieve therapeutically meaningful protein lowering.

We also observed that deletion sizes in vivo were more confined than those seen with longer-lasting expression systems, suggesting that delivery format can influence the deletion distribution—potentially a useful lever for translation.

Third, because ATTR is ultimately a human disease, we evaluated Cas3 editing in a TTR exon-humanized mouse model, where the mouse coding region is replaced with the human sequence. This allowed us to measure circulating human-sequence TTR and to examine protein-level consequences after editing. In this model, Cas3 again produced strong TTR lowering. Importantly, our protein analyses suggested a low likelihood of generating undesirable edited TTR variants after Cas3 treatment.

In aged mice, Cas3 treatment was also associated with attenuation of macrophage-associated TTR deposition in the heart, linking durable TTR lowering to disease-relevant tissue outcomes. While this model does not fully reproduce advanced amyloid pathology detectable by classic histology, it captures early deposition and inflammatory responses relevant to ATTR progression.

How does this fit alongside Cas9?

Cas9-based editing has already set an important benchmark for ATTR, and its clinical progress is a landmark achievement. Our goal is not to diminish that success, but to expand the therapeutic toolkit. Cas3 offers a mechanistically distinct option—deletion-based disruption—that may be particularly well suited to diseases where robust gene knockout and minimizing unexpected protein products are priorities.

Looking ahead, further optimization, long-term safety and durability studies, and evaluation in larger animal models will be essential. Nevertheless, our study demonstrates that Cas3 can be used for in vivo therapeutic gene disruption in the liver and can achieve substantial lowering of circulating TTR in disease-relevant models. We hope it encourages broader thinking about how different CRISPR mechanisms can be matched to different therapeutic goals as genome editing medicines continue to evolve.

Related content:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-025-02949-6

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Biotechnology

A monthly journal covering the science and business of biotechnology, with new concepts in technology/methodology of relevance to the biological, biomedical, agricultural and environmental sciences.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in