Wildlife declines where wars rage

Published in Ecology & Evolution

The paper in Nature can be found here

Last month, Filipe Nyusi, the President of Mozambique, made a remarkable visit to one of his country’s remarkable conservation areas, Gorongosa National Park. Nyusi was there to negotiate a durable peace with Afonso Dhlakama—Nyusi’s most prominent political opponent and a onetime rebel-army commander. The visit and continuing progress toward permanent peace in Mozambique paralleled a simultaneous transition in Gorongosa’s history. Once a place that epitomized the tragic environmental consequences of Mozambique’s 1977–1992 civil war—over 90% of Gorongosa’s large mammals (elephants, buffalo, zebra, wildebeest, and many antelope species) were killed during the war—wildlife (Fig. 1) have recently repopulated the park to an astonishing degree in recent years1–3.

I’ve studied the ecology of Gorongosa and its recovery since 2012, and shortly after my first visit I grew curious about whether the park’s tragic history was representative of the intersection of armed conflict and conservation elsewhere. Indeed, between 1950 and 2000, the 34 classically identified biodiversity hotspots—areas of especially high species endemism and conservation threat—contained five times more major conflicts than expected given their area4, but no study had presented a synthetic quantitative look at how war affects biodiversity.

One possible reason for the intersection of conflict and conservation priorities is that both conservation threat and conflict risk are associated with rapid human population growth, poverty, and institutional decay (themselves the result of complex historical, geopolitical, and economic factors). Paul Dutton, who worked as a wildlife technician and helped re-open Gorongosa just after the civil war in 1994, told me that in the absence of effective park management authority, he and his colleagues were left to confiscate AK47s from soldiers who were using them to poach wildlife. This kind of dynamic was hardly unique to Mozambique: Brian Huntley’s recent book Wildlife at war in Angola details the decline of scientific and conservation infrastructure during that country’s long civil conflict.

As for any conservation threat, understanding and managing the risk posed to biodiversity by conflict requires quantitative data on the particular species and habitats threatened. However, nearly all previous studies of the effects of conflict on conservation outcomes are case studies, making the development of any broad policy or management prescriptions for conserving biodiversity during and after conflicts difficult.

In fact, existing case studies show that conflict can have a wide range of environmental impacts: deforestation by refugees in need of fuelwood, and elephants killed by soldiers who trade ivory for weapons. There are also, however, sporadic reports of positive impacts of war on wildlife. For example, the ‘bush war’ in Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, putatively made savanna habitats too dangerous even for poachers, allowing a decade-long increase in wildlife abundance5. Outside Africa, the Korean Demilitarized Zone has acted as a de facto conservation area for 65 years6. Thus, it was uncertain at the outset of my research what the net impact of conflict on wildlife has been, although I suspected that negative impacts would predominate.

To quantify the net effect of war on wildlife, I extracted large mammal population estimates from about 500 articles and reports. Where comparable data were available for greater than one time point for a given population, we computed the population trajectory—how fast it was growing or declining. This data-gathering process was necessary because few individual studies have reported population estimates spanning periods of both peacetime and war. We then matched the population trajectories’ times and locations with existing spatio-temporal databases of conflict events7,8.

For several reasons, we focused on large mammals. First, they are a charismatic group that play vital roles in ecosystems and support economically important tourism enterprises throughout the continent. Second, their populations have been declining since the 1970s across much of the continent9. And finally, because large mammals are attractive to hunters for their desirable meat, they may be especially susceptible to war-driven impacts.

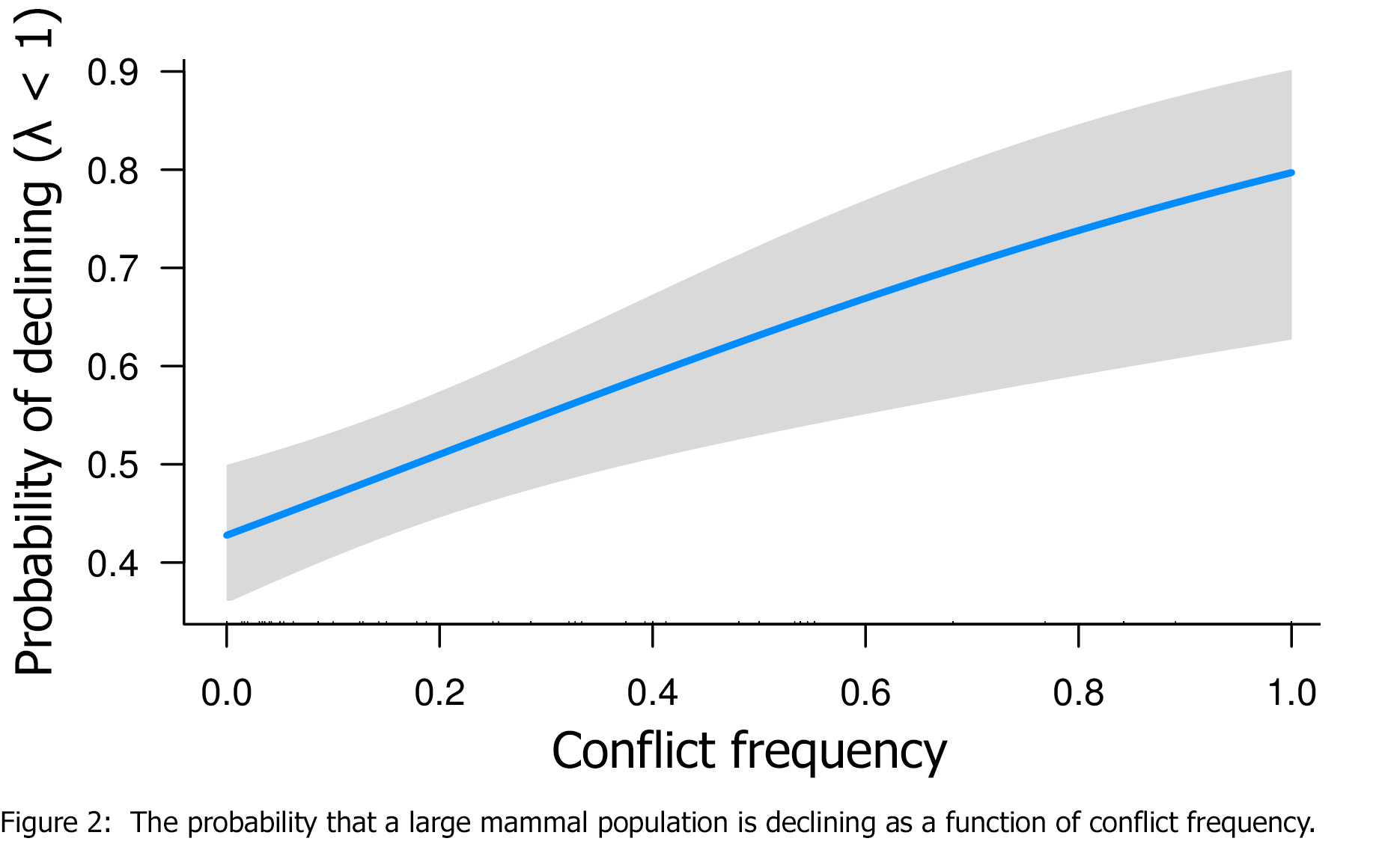

We found that the frequency of declining populations increased sharply with the frequency of conflict (Fig. 2). In addition, while the average population trajectory in peaceful parks was almost exactly at the level of replacement, as little as one conflict event in two-to-five decades pushed the average population trajectory below replacement!

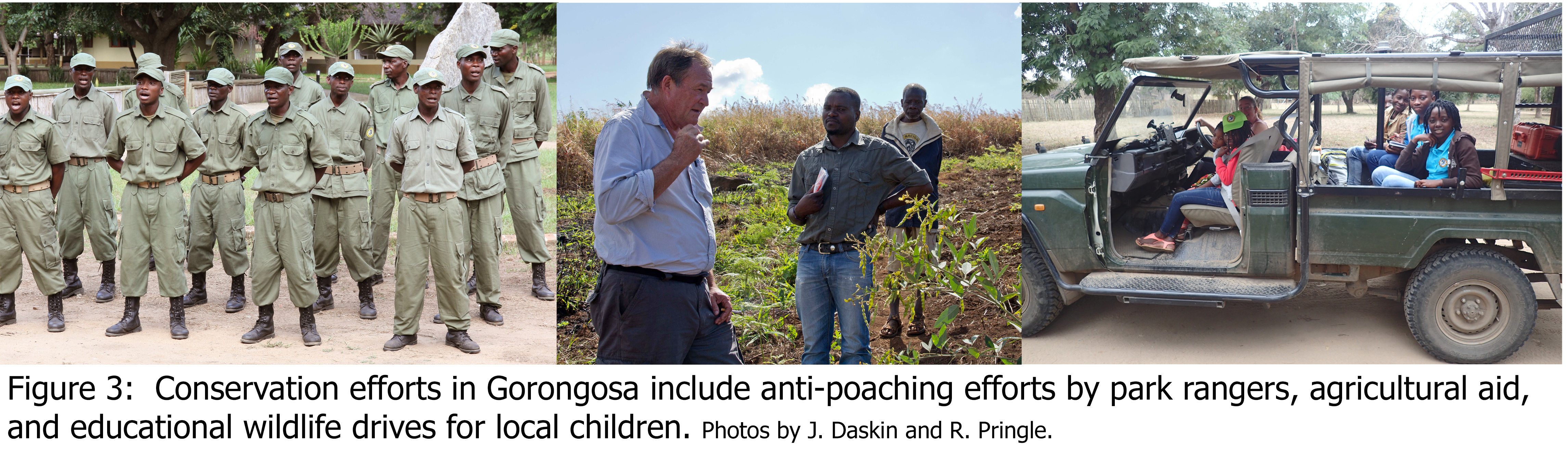

Importantly, however, although all populations from high-conflict frequency sites in our dataset were declining, we found relatively few absolute extinctions. Thus, there is the potential for restoration of post-war mammal assemblages, as has occurred in Gorongosa. Gorongosa’s ecological recovery is mirrored and strengthened by an ongoing socio-economic restoration; success in human development and biodiversity conservation are innately coupled. In Gorongosa, this includes agricultural and medical programs for communities living around the park, plus an ambitious program that brings hundreds of local children to view the now-abundant wildlife each year (Fig. 3). In many parts of Africa, economic conditions make visiting parks and observing their wildlife all-but impossible for people living protected areas, diminishing the chance that people choose to value wildlife as anything but meat. Human development is critical to helping reduce reliance on bushmeat, and to empowering local people to manage, appreciate, and study their local conservation areas. While the details will vary from place to place, similar strategies should be considered in other protected areas with the potential for post-war rehabilitation3 of wildlife populations.

References

1. Daskin, J. H., Stalmans, M. & Pringle, R. M. Ecological legacies of civil war: 35-year increase in savanna tree cover following wholesale large-mammal declines. J. Ecol. 104, 79–89 (2016).

2. Wilson, E. O. War and redemption in Gorongosa. Am. Sci. 102, 214 (2014).

3. Pringle, R. M. Upgrading protected areas to conserve wild biodiversity. Nature 546, 91–99 (2017).

4. Hanson, T. et al. Warfare in biodiversity hotspots. Conserv. Biol. 23, 578–587 (2009).

5. Hallagan, J. B. Elephants and the war in Zimbabwe. Oryx 16, 161–164 (1981).

6. Kim, K. C. Preserving biodiversity in Korea’s demilitarized zone. Science 278, 242–243 (1997).

7. Tollefsen, A. F., Strand, H. & Buhaug, H. PRIO-GRID: A unified spatial data structure. J. Peace Res. 49, 363–374 (2012).

8. Sundberg, R. & Melander, E. Introducing the UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset. J. Peace Res. 50, 523–532 (2013).

9. Craigie, I. D. et al. Large mammal population declines in Africa’s protected areas. Biol. Conserv. 143, 2221–2228 (2010).

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Good to know that war did have some positive effects although indirectly. However this study does bring out a new outlook on the effects of wars on animal life, which normally does not receive attention.