Invasion Debt: Invasive Species in the Middle East

Published in Earth & Environment and Ecology & Evolution

Many nations have adopted international conventions on wildlife conservation and biodiversity protection in recent decades, joining the global movement toward environmental protection. These early legal commitments, often supported by regional coordination agreements, represent promising beginnings. Yet two decades later, the story has become far more complicated.

The question today is not whether countries have regulations to combat invasive species; many clearly do. The question is whether those regulations address the fundamental ways in which well-intentioned development initiatives—from infrastructure expansion to agricultural intensification to landscape restoration projects—are creating the very conditions for biological invasions to flourish.

Saudi Arabia exemplifies this challenge: despite adopting the Convention on the Conservation of Wildlife and Their Natural Habitats in 2003 and implementing multiple regulatory frameworks through the GCC regional coordination structure, the Kingdom continues to grapple with whether its regulatory approach adequately addresses the invasive species consequences of rapid development and environmental management initiatives.

A Regulatory Timeline: A Story of Increasingly Sophisticated Inaction

Many countries show a pattern of institutional development without changing invasive species policies. Early regulations—like plant quarantine laws and biosecurity standards—build a prevention foundation. However, later reorganisations toward specialised governance can cause fragmentation across conservation, vegetation, compliance, and infrastructure. Regulatory packages often introduce large-scale penalties that act mainly as deterrents after invasions occur, not prevent them. This flaw means regulations punish invasions but do not address the factors that make invasions likely or profitable. As a recent actor in the space, Saudi Arabia exemplifies this: from 2003 to 2025, it developed an impressive regulatory structure, including the 2005 Plant Quarantine Act and 2020 penalties of about 130 USD per invasive plant. Yet enforcement gaps, coordination issues, and the inability to address fundamental conditions—often linked to development—still allow invasions to thrive.

The Overlooked Vector: Greening as Invasion Enabler

The Middle East is investing heavily in greening, with high-profile reforestation and landscaping projects that support sustainability goals. These efforts address desertification, climate adaptation, and urban livability, aligning with the Sustainable Development Goals and contributing to those aims. However, they also serve as invasion pathways. The 2025 Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution article, "Increasing invasion debt through good intentions: the risk and responsibilities of greening initiatives in the Middle East," questions whether these well-meaning efforts unintentionally increase the spread of invasive species. The mechanism is simple: greening requires lots of propagation material, fueling a thriving horticulture industry. In Saudi Arabia, demand for ornamental plants is rising due to city development projects.

The problem: horticulture is a major pathway for the introduction of invasive species globally. It’s a significant risk, often the primary vector, as species with traits such as tolerance, rapid growth, competitiveness, and high reproductive rates become invasive. Signs are already clear, unpublished data show that about 10% of all regulated invasive plants in Saudi Arabia are cultivated by nurseries, potentially unaware or ignoring regulations. This ongoing activity directly contributes to invasions despite greening efforts.

Invasion Debt

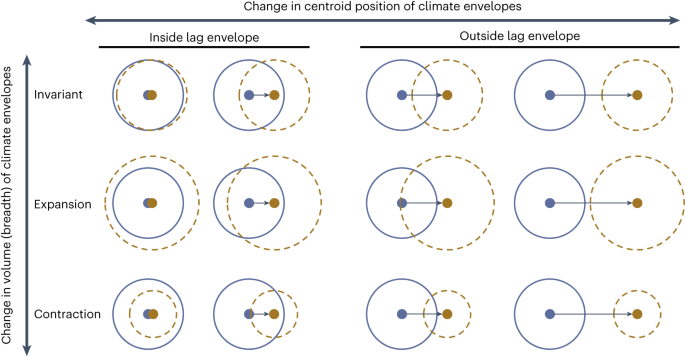

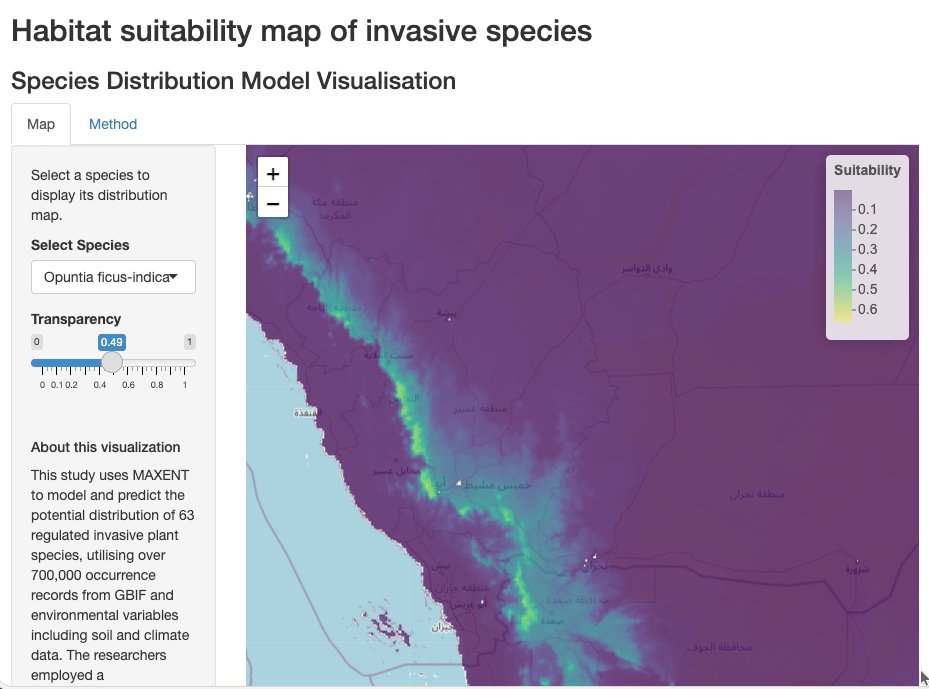

By 2016, Thomas et al. documented 48 invasive plant species in Saudi Arabia, highlighting six major invaders like Prosopis juliflora, Opuntia, and Nicotiana glauca. Their study emphasised the ongoing invasion, ecological harm, and dynamic invasion patterns, including invasion lags and debt. Across eight invaded regions, invasion lag, the delay between species introduction and rapid expansion, was observed in 35% of cases across eight regions, averaging 40 years, with some up to 320 years (Robeck et al 2024). This delays management responses, often leading to late, costly interventions. Saudi Arabia’s regulations mainly address visible, current invasions, overlooking quiet, late-emerging species, which are usually harder and more expensive to control later. For example, Prosopis juliflora has expanded 80-fold over 30 years in the UAE, costing $11–22Mio annually in energy and infrastructure. The Red Palm Weevil incurs about $25.92Mio yearly in the GCC. These costs highlight the need for early prevention, as delayed action results in higher costs and ecological damage.

Regulation and Reality

By 2024, Saudi Arabia will have developed a comprehensive invasive species management framework, including the National Plan, an updated invasive species list with over 13 priority species, and a list of regulated plants. A stakeholder workshop occurred in 2022, and a marine species monitoring program started in 2024-2025. However, enforcement is sporadic, awareness among practitioners is limited, and there's a misalignment between regulations and economic incentives. Landscapers and developers are pressured to deliver quick results, favouring fast-growing ornamental species, even if regulated as invasive, because penalties are manageable compared to the costs of native species. Penalties alone are ineffective without proper enforcement, monitoring, and inter-agency coordination. Notably, around 10% of regulated invasive plants are still cultivated, indicating regulatory failure concealed as institutional progress.

Science-Policy Interface

In 2025, major advances in invasion ecology and science include Haq et al.'s detailed analysis of Saudi Arabia’s alien flora and Robeck et al.'s large-scale use of species distribution models (Link to SDMs) to predict invasive plant ranges. Only recently, Al-Bakre et al. developed the first climate-change-informed SDM for Optunita species in the region. These tools support evidence-based policy by identifying management zones, forecasting expansion, and monitoring effectiveness. However, SDMs have limitations; they perform best under equilibrium assumptions—rare for invasive species—since these are actively expanding and adapting, not at equilibrium. They also ignore ecological mechanisms like biotic interactions, Allee effects, and eco-evolutionary processes, predicting suitability but not invasion success, which depends on dispersal and biotic resistance. Therefore, application of SDMs should be cautious, recognising their uncertainties and avoiding overinterpretation by policymakers.

A Marine Blind Spot

The final key gap is the marine invasion issue. The 2024-2025 National Program for Tracking Invasive Marine Species, a partnership between the National Centre for Wildlife and King Abdullah University for Science and Technology, marks the first national effort to identify non-native marine species in Saudi waters. Early results show 181 potential non-native species in the Red Sea and 168 in the Arabian Gulf, mainly near ports and coastal infrastructure. This blind spot, only recently addressed, involves species dispersing mainly via shipping and ballast water, with challenges in management and damages such as impacts on fisheries and ecosystems. The focus on marine invasions around ports underscores how infrastructure and trade routes facilitate invasions, making their prevention linked to managing global maritime trade, which is politically and economically challenging.

Two decades of regulation show uncertain results. Saudi Arabia has a comprehensive legal framework and scientific investments for managing invasive species, with a genuine commitment to biodiversity. However, regulations haven't changed incentives or behaviours, as invasive species are still actively cultivated despite bans. Greening initiatives improve urban areas but often ignore invasion risks, with penalties focused on violations rather than prevention.

The full impact of past invasions is still unfolding, and the ongoing invasion debt poses future challenges.

Current policies may only manage visible crises, not prevent the future exponential spread of species. This isn't a call to stop efforts but a warning that regulations alone aren't enough—systematic analysis and advanced response strategies will be needed as invasive species continue to threaten ecological and economic stability.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Ecology & Evolution

This journal is interested in the full spectrum of ecological and evolutionary biology, encompassing approaches at the molecular, organismal, population, community and ecosystem levels, as well as relevant parts of the social sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning of global peatlands

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jul 27, 2026

Understanding species redistributions under global climate change

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jun 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in