Against transcendentalism and reductionism in arts and health

Published in Neuroscience, Education, and Mathematical & Computational Engineering Applications

Arts and health

In recent years, the relationship between the arts and health has regained global attention. Initiatives such as the Jameel Arts & Health Lab and the WHO–Lancet series have made clear that creative engagement is not a marginal topic but one that should influence health policy. The most recent WHO global review of arts and health provided compelling evidence that artistic practices (from music and dance to theater and visual arts) enhance wellbeing and can even shape the way experiences are biologically embedded in our bodies and brains. And yet, despite this momentum, the field remains constrained by two opposing prejudices: one originating from the arts themselves and another that persists in the biomedical sciences.

The mirage of transcendence

The first prejudice could be called aesthetic transcendentalism. This perspective holds that art is the domain of professional artists alone, a rarefied activity detached from ordinary life. According to this view, creativity belongs to the stage, the gallery, or the studio, not to kitchens, streets, or living rooms. A related assumption is that art is ineffable and cannot be measured. At best, its effects on health are secondary, accidental byproducts of something essentially beyond the scope of science or health. This way of thinking makes artistic practice exclusive, inaccessible, and disconnected from broader debates about public health.

The biometric prison

Opposite this lies the biomedical prejudice. From this perspective, artistic practices are dismissed as lacking the rigor of clinical interventions. Art is often viewed as something that can uplift the spirit, but it does not produce measurable biological changes. Evidence in favor of its impact is usually judged to be anecdotal, underpowered, or lacking mechanistic clarity. In this view, art is not a real intervention because it cannot rival pharmacology or surgery in terms of demonstrable outcomes.

Our approach

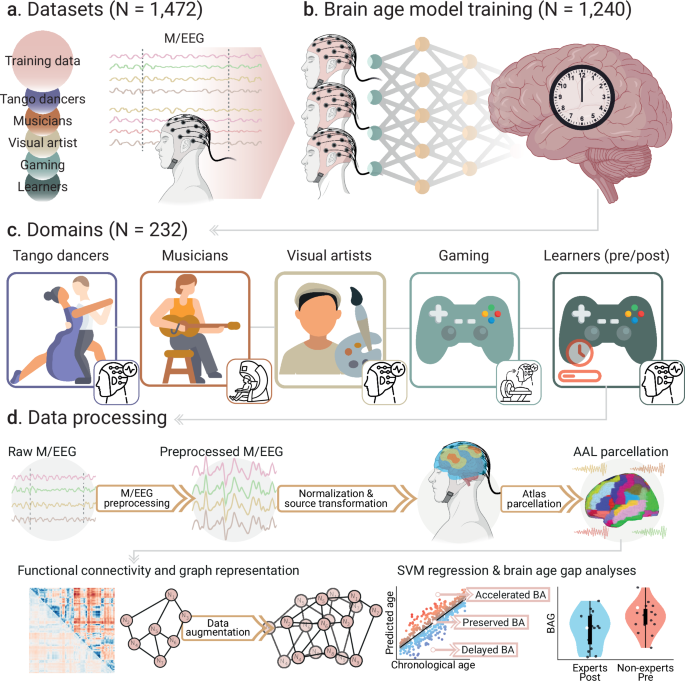

A new study challenges both prejudices. Published in Nature Communications and highlighted by Nature, we analyzed nearly 1,400 participants from multiple countries. It combined a normative modeling of age, as well as expert and non-expert groups (tango dancers in Argentina, musicians in Canada, visual artists in Germany, and video gamers in Poland), with a short-term learning experiment in which non-experts trained for 30 hours in the strategy game StarCraft II (the same video game of the expertise design). We used EEG and MEG data to train brain clocks, computational models that predict biological brain age based on patterns of brain dynamics. By comparing predicted age to chronological age, we derived brain age gaps, a measure of whether a brain appears older or younger than expected. We employed graph theory, whole-brain biophysical modeling, and Neurosynth meta-analyses to investigate the underlying mechanisms of these effects.

Across every domain of expertise, creative practitioners had significantly younger brains than their matched non-expert peers. Tango dancers showed brains more than seven years younger than their actual age, musicians and visual artists around five to six years younger, and gamers four years younger. Even in the short-term learning study, after only 30 hours of training, participants’ brains were still functioning at a younger level than before. The more skilled the individual, the larger the delay in brain aging. These effects were grounded in changes to the frontoparietal brain hubs, regions that are especially vulnerable to aging. Creative practice enhanced the efficiency of these networks, strengthened local and global connectivity, and modulated biophysical coupling, signatures of neural plasticity. The effects were domain-free: whether through dance, music, visual arts, or gaming, the underlying pattern of delayed brain aging was consistent.

These findings directly confront both prejudices. Against aesthetic transcendentalism, they demonstrate that creativity is not confined to professional artists. Everyday practices, from tango classes to online gaming, carry measurable benefits for brain health. Far from being beyond measurement, these effects can be quantified precisely through aging clocks and computational neuroscience. In opposition to biomedical reductionism, the study reveals that the arts are not biologically neutral. Creative experiences are associated with reshaped functional brain organization in ways that are as measurable and mechanistic as drug trials or other interventions.

These results also challenge the persistent view that video games are meaningless to brain health. As with the arts, what matters is the quality of the experience: not all games can preserve brain health. Strategic, attentional, and cognitively demanding games appear to confer the most potent protective effects. Importantly, these benefits do not require deep or prolonged immersion, and moderate engagement can yield positive outcomes. Excessive or compulsive gaming, in contrast, has been linked to poorer mental health. Yet, given their accessibility and widespread appeal, video games could become powerful allies to complement pharmacological, physical, and behavioral interventions aimed at preserving brain health.

As creativity is associated with delayed brain aging, arts and health should not be considered secondary luxuries, but interventions for both prevention and wellbeing. Creativity is not a soft add-on to medical care, nor an ineffable mystery that escapes analysis. Avoiding the twin pitfalls of aesthetic transcendentalism and biomedical reductionism can help to integrate arts-based strategies into public health, education, and clinical practice. The arts and science, far from being opposing worlds, converge to enhance human health.

AI has designed the poster figure under the supervision of the authors.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Your space to connect: The Psychedelics Hub

A new Communities’ space to connect, collaborate, and explore research on Psychotherapy, Clinical Psychology, and Neuroscience!

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in