An Unexpected Journey: Finding a paleoearthquake and a river avulsion

Published in Earth & Environment

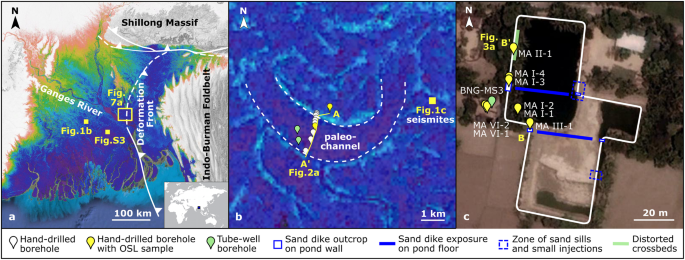

Liz Chamberlain and Steve Goodbred, both sedimentologists from Vanderbilt University, were traipsing around coastal Bangladesh in March 2018 when they saw the sand dikes. They had come to Bangladesh to investigate how fast rivers meander, or shift, in the coastal part of the Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta in Bangladesh. With them were Steve’s graduate student Rachel Bain, and Abdullah Al Nahian and Mahfuzur Rahman from Dhaka University. The team was taking sediment samples from loops in the many rivers that cross the lower delta plain to date the sediments left behind as the rivers shifted. Midway through the trip, they came across a large pond that had just been dug for storing fresh water. On the flank of the pond were vertical sand dikes up to a 30-40 cm wide, cutting through the horizontal layers of sediments. Injections of sand through sediment layers is a well-known effect of earthquakes. The shaking from an earthquake separates the sand grains and increases pressure until it erupts like a sand volcano forming a “seismite”. But here, the seismites were far from the tectonically active parts of Bangladesh and India that could be the source of the earthquake, and the size of the dikes so far from the epicenter suggested a large earthquake.

.jpg)

Liz and Steve had been drawn to the local area by a broad abandoned river channel preserved as a low-elevation curve clearly visible in a digital elevation model. The abandoned channel was about 1.5 km wide and used for rice cultivation. The morning had been spent in the hot sun surveying the abandoned channel, and it was late in the day when the team discovered the seismites in the freshly dug pond walls. With the assistance of Abdullah and Mahfuzur as translators, Steve arranged with the pond owner to not fill the pond with water overnight so they could continue their investigation.

.jpg)

Realizing the importance of what they had found and the immediacy of documenting it before the pond was inundated, they contacted us. As experts in geophysics, structural geology, and neotectonics, we have more experience with the tectonics of the region and conditions for the development of sand dikes. It is not easy to distinguish a seismite from other sand dikes. For example, sand dikes can also be caused by varying degrees of overburden or excess pore water pressure at depth. To recognize whether it could really be seismites, it was necessary to document the structure as well as possible. The first task was to immediately improvise a short-order research design. The next day, the field team returned to the pond and documented all aspects that could help in understanding both the fluvial and seismic history of the site – sediment texture, dike dimensions and orientation, optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) samples to date the sediments, and more.

.jpg)

We tested the hypothesis that these really were seismites from all sides - are the veins systematically oriented in the stress field? Are there signs of vertical transportation of sand within the dike? Is the dike away from topographic features that could trigger differential loading? Only when all other possible explanations were shown to be inadequate were we sure that they were seismites. Follow-up work, after the field work was completed, looked at potential sources for the earthquake, the stress field of the delta plain, and empirical relationships from prior research on dike width, distance to origin, and earthquake magnitude.

.jpg)

We found that the likely potential sources of the earthquake were over 180 km away. Investigating the size of the sand dikes with the distance to the earthquake, we concluded that the likely size of the earthquake was M7-8.

.jpg)

The OSL ages of the samples at the sand dikes and the abandoned river channel showed that both channel abandonment and dike formation occurred at the same time, ~2,500 years ago. The large scale of the channel, together with finding a similar channel that was abandoned at the same time ~85 km downstream, suggests that this was a major avulsion of the Ganges River. Rivers in deltas deposit sediments that build up their elevation with time. Eventually, they avulse, or shift, to a new lower elevation pathway. For example, the Mississippi River has avulsed 7 times over the Holocene. The coincidence of timing and the Ganges River avulsion and the earthquake suggests that the avulsion was triggered by the earthquake. This is the first confirmation that earthquakes can drive avulsions of immense rivers in deltas, a potential cascading hazard in susceptible locations.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in