Buried deep freshwater reserves beneath salinity-stressed coastal Bangladesh

Published in Earth & Environment

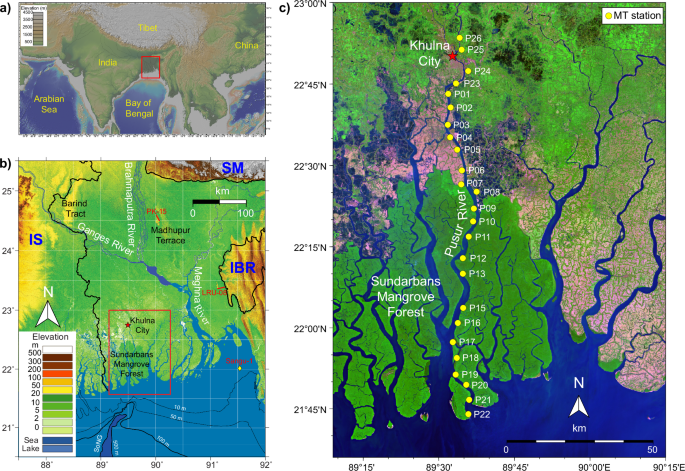

In large parts of the coastal zone of Bangladesh the shallow groundwater is salty. This limits rice growing to just the rain-fed Aman rice in the summer to fall. For drinking water, they have to store the summer monsoon rain in ponds, but it sometimes runs out before the next rainy season. However, deep in the Earth, in sediments from the last ice age, fresh water can sometimes be found. It is used for drinking water in some places, but a well deep enough to reach it is too expensive for most Bangladeshis. Another issue is that little was known of the extent of this deep fresh water aquifer or where it could be found; deep wells were just hit or miss. It was believed that there were pockets of fresh water, but no way to predict where they were or knowledge of the thickness of the aquifer. To map the distribution of this deep fresh and saline groundwater in coastal Bangladesh water, we assembled a team with a diverse set of expertise from the U.S. and Bangladesh.

Since salt water conducts electricity much better than fresh water, we used electromagnetic methods to image the distribution of fresh and saline groundwater along two rivers in Bangladesh. Magnetotellurics (MT) uses naturally occurring electromagnetic waves to image the structure below the instrument. High frequencies give shallow results and lower frequencies give deeper results. To image the upper few hundred meters, we deployed the instruments overnight. To conduct the experiment, , we shipped 1400 lbs. of equipment to Bangladesh and 12 of us will be traveling on the M/V Kokilmoni (Photo 1), an 85-foot boat that usually takes tourists to the Sundarbans, the world’s largest mangrove forest. Getting to this point had some of the most complicated logistics of any project I have had. We faced problems with insurance, shipping the equipment, getting the right batteries, visas, and the list goes on. Finally, everything got sorted out and we were able to conduct our 25-day cruise only a few days late.

Traveling by boat, we deployed 2-4 instruments each day, returning in the morning to pick them up and deploy the next set farther downstream. For the line in this paper, we spent over a week doing this to collect the data. At each site we have a central recorder and battery. These are connected by cables to north-south, east-west and vertical magnetometers. These are cylinders about 3 feet in length that need to be buried (Photo 2). The most difficult is the vertical and we brought post-hole diggers to get them in the ground. Finally, there are small electrodes for the electric field that are placed ~50 meters away from the center in the four cardinal directions using a compass and electronic rangefinder. They also needed to be buried to minimize noise.

.jpeg)

The first few days were spent in large fallow fields, since crops are limited in the dry season. We used satellite images to choose the locations, but then had to deal with cows and, especially, goats who could eat the cables. Then we entered the Sundarbans, and found it quite different from working in populated areas. We simply picked locations at the correct distance downstream and entered the forest (Photo 3). We hiked through the bush using deer trails when possible and tried to find enough of a clearing to set up the central receiver location. For the magnetometers, the challenge was finding a spot of the correct orientation that is free of tree roots, especially the aerial roots that allow mangroves to live in salt water.

The electrodes became the slowest part of the deployments. Having to go directly N, S, E or W, we could not follow trails, but had to go straight through the trees and brush, and their thorns. We also could not see 50 m through the forest and had to find more creative ways to position the electrodes. We also needed one of the armed guards to go with the group to the electrodes because of the risk of tigers (Photo 4). Because of the tigers, everyone stayed in groups of at least 4 people with an armed guard. We made sure each group had everything needed as one person could go back alone to get something that was forgotten. We also continuously made lots of noise. While we saw lots of tiger footprints, we never saw a tiger. We did see lots of deer, crocodile, wild boar, egrets, storks, monkeys and other animals.

After the field campaign (Photo 5), the lead authors, Huy Le and Kerry Key, started processing the data, which showed fresh water beneath the shallow saline water, as expected. However, to our surprise, the fresh water was interrupted by a 20-km gap of saline breaking it into two patches. This confused us at first, but then we realized that the saline water corresponded to the position of the valley that was incised by the Ganges River during the low sea level at the last ice age, previously mapped by our colleagues. Now we could make sense of the pattern. When sea level rose at the end of the ice age, the incised river valley was filled with marine waters as a large estuary. The pattern of fresh and saline water at depth was not just random pockets of preserved fresh water, but were controlled by the geology and location of the incised river valleys and the high ground between them. The river valleys contained saline water and the intervening strata held the deep fresh water. This provides a framework for understanding the distribution of fresh and saline deep groundwater that can be used for locating where future deep wells can find drinking water. Similar interactions of sea level cycles and fluvial incision may shape deep fresh aquifers in other coastal deltas and continental margins.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in