Behind the Paper: Ensemble ML and SHAP for hybrid polypropylene composites

Published in Materials

What was the problem?

Polypropylene (PP) is everywhere—from appliance housings to automotive trim—but tuning its mechanical performance with eco-friendly reinforcements is still a balancing act. We explored a hybrid system of long flax fiber bundles (LFF), basalt fibers (BF), and rice husk powder (RHP). Each ingredient pulls properties in different directions: BF boosts stiffness, flax can raise strength at modest loadings, and RHP helps processability and sustainability but can soften the matrix if overused. Running a full factorial campaign would be slow and costly, so we asked: could machine learning help us map the design space with only a compact Box–Behnken plan?

Why ensembles, not a single model?

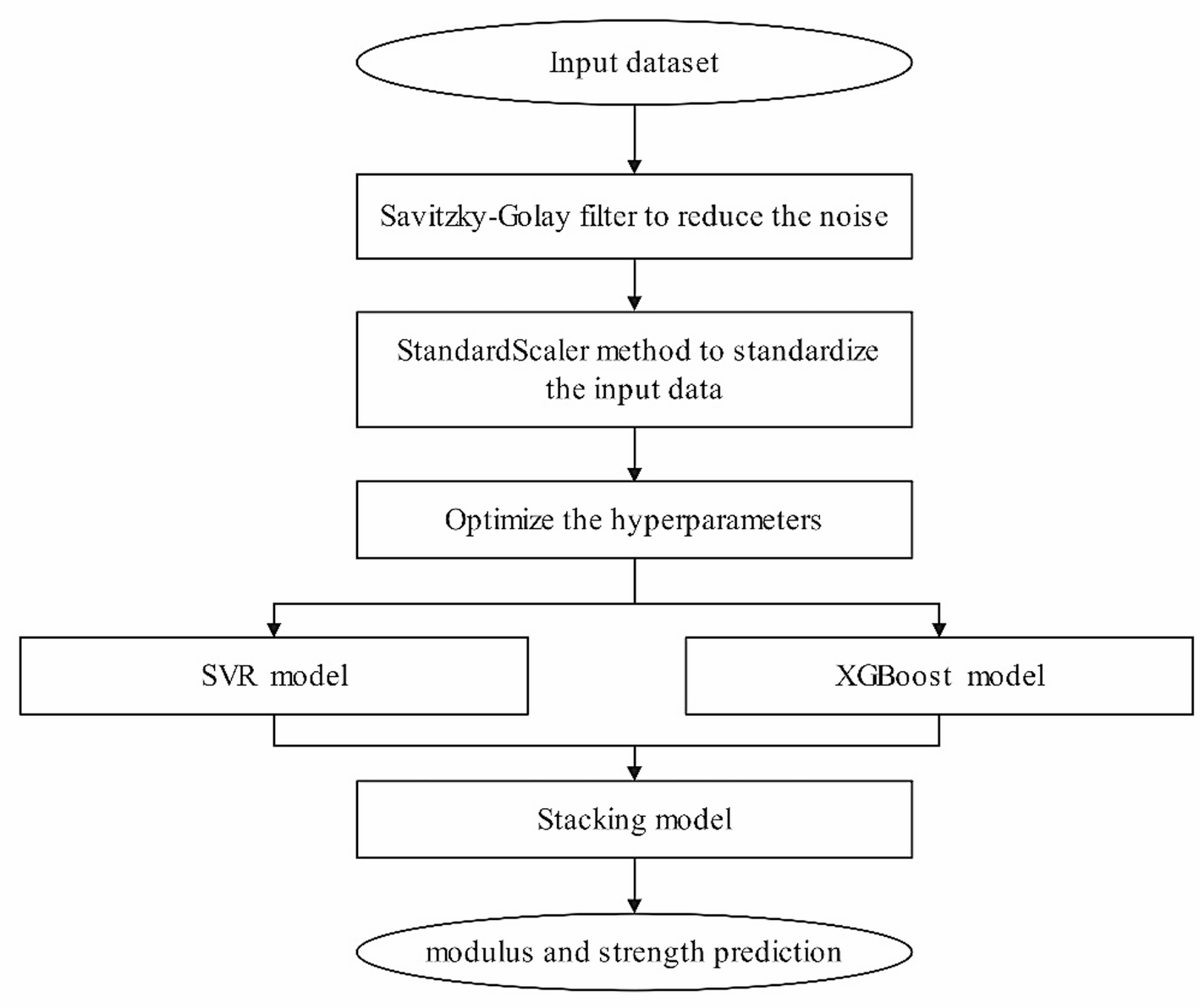

Small materials datasets are noisy and rarely linear. Single learners often overfit, especially when variables interact. We therefore stacked two strong but complementary base learners and tuned capacity carefully with cross-validation. Stacking reduces variance by letting models “vote,” while still capturing non-linear trends. We also kept a strict separation of training, validation, and a 20% hold-out set so our reported skill reflects true generalization inside the tested route.

How did we keep it honest?

Before modeling, we treated the data like we would treat a specimen: inspect it. Histograms, KDEs and boxplots ensured every factor level was represented and flagged one clear modulus outlier (>10 GPa). Pair plots helped us see raw tendencies (%BF and %RHP versus tensile strength/modulus) without hiding behind a model. During training, we used k-fold cross-validation and capped complexity (depth, estimators, regularization) to avoid optimistic results.

Why SHAP (and friends)?

A prediction is only useful if engineers can act on it. SHAP values provide per-feature, per-sample attributions for tree models, telling us how much each variable nudged a prediction up or down. We paired SHAP with permutation importance (model-agnostic), partial dependence (PDP) and accumulated local effects (ALE) to see both global and local behavior. The takeaway was intuitive and actionable: BF dominates modulus gains, but strength benefits from a balanced trio—too much of any one component quickly flattens returns. These insights align with micromechanics expectations about stiffness transfer and embrittlement at high rigid-filler content.

What did we learn for design?

The ensemble reproduced measured trends on cross-validation and on the unseen hold-out set. From the SHAP/PDP landscape we highlighted composition windows where tensile strength improves ~2× over neat PP while modulus climbs strongly: moderate BF with supportive flax plies and controlled RHP. In practice, this narrows down trial-and-error—teams can start within these windows, then fine-tune around processing realities such as fiber length retention or porosity.

Limits you should care about

Our goal wasn’t a universal model for “any” PP composite. We fixed processing (extrusion → hot press → injection molding) to isolate composition effects. That means the model explains variance due to %BF, %RHP, and flax ply count within this route; jumping to a very different line or tool will change the microstructure, and models should be retrained or updated. Also, small materials datasets make uncertainty quantification valuable; future work could add conformal prediction intervals so designers see both a forecast and its confidence band.

Why this matters beyond our system

The workflow—compact DOE, capacity-controlled ensembles, and transparent explanations—generalizes to many data-limited materials problems: bio-fillers in thermoplastics, multi-phase binders, or even cementitious systems. The key is to pair domain priors with honest diagnostics and keep explanations close to mechanisms engineers trust.

A note on sustainability

Flax and rice-husk powder are renewable or waste-derived. Being able to forecast properties with fewer physical trials lowers energy, labor, and scrap. In other words, better data practices are also greener practices.

Where to read the paper

The research article is open access in Discover Materials: DOI 10.1007/s43939-025-00406-4. A shareable link is available via Springer Nature’s initiative: rdcu.be/eQUMB.

Follow the Topic

-

Discover Materials

This is a broad, open access journal publishing research from across all fields of materials research.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Reuse and Recycling of Waste in the Construction Sector

The construction sector is one of the largest producers of waste, contributing significantly to global environmental challenges. In recent years, there has been a growing emphasis on sustainable practices, particularly in the reuse and recycling of construction and demolition waste, municipal solid waste, and industrial waste. Addressing the environmental impact of this waste is critical for sustainable development. This collection explores innovative strategies, technologies, and policies aimed at minimizing waste, promoting resource efficiency, aiming to reduce landfill dependency, and advancing sustainable building practices within the construction industry.

This collection invites comprehensive research and practical insights into various aspects of waste management in the construction sector, including:

1. Construction and Demolition Waste: Innovative methods for recycling and reusing concrete, asphalt, metals, wood, and other materials from construction and demolition sites.

2. Municipal Solid Waste: Strategies for integrating recycled municipal solid waste materials, such as glass, plastics, and organic matter, into construction projects.

3. Industrial Waste: Techniques for repurposing industrial by-products and waste materials in construction, including slag, fly ash, and manufacturing residues.

4. Policy and Regulation: Examination of governmental policies, regulations, and incentives that facilitate the reuse and recycling of various waste types in construction.

5. Sustainable Construction Practices: Implementation of circular economy principles in construction, including design for disassembly, modular construction, and sustainable material sourcing.

6. Environmental and Economic Impacts: Evaluation of the environmental benefits and economic feasibility of recycling and reusing different types of waste in the construction sector, including life cycle and cost-benefit analyses.

7. Technological Advances: Development and application of advanced technologies, such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, and robotics, to optimize waste management and recycling processes in construction.

8. Material Innovation: Research new materials and products derived from recycled waste, assessing their performance, durability, and potential applications in construction.

9. Case Studies and Best Practices: Documentation of successful projects and initiatives that highlight effective reuse and recycling strategies in the construction industry.

By bringing together cutting-edge research and practical insights, this collection aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state and future directions of waste reuse and recycling in the construction sector. Contributions from academics, industry professionals, policymakers, and other stakeholders are encouraged to foster a multidisciplinary dialogue and drive meaningful change in the industry.

Keywords: Construction Waste Management; Recycling Techniques; Reuse Strategies; Sustainable Construction; Municipal Solid Waste; Environmental Impact; Circular Economy; Industrial Waste Recycling

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 30, 2026

Materials in Structural Engineering: Challenges and Innovations under Extreme Loading Conditions

In the realm of materials science and engineering, the quest for robust, resilient materials capable of withstanding extreme loading conditions is more pressing than ever. The field of structural engineering, at the forefront of this endeavor, faces constant challenges posed by natural disasters, industrial accidents, and deliberate acts of violence. The ability of structures to endure such events depends crucially on the properties and performance of the materials from which they are constructed. Discover Materials, as part of the Discover journal series committed to advancing materials research, provides an ideal platform for addressing these challenges and exploring innovative solutions.

The proposed topical collection, titled "Materials in Structural Engineering: Challenges and Innovations under Extreme Loading Conditions," aims to delve deeply into the intersection of materials science and structural resilience. This collection is driven by the urgent need to develop materials that can withstand diverse forms of extreme loading, including blast and impact forces, while maintaining structural integrity. Real-world scenarios underscore the importance of this research: from safeguarding critical infrastructure against terrorist attacks to preparing communities for natural disasters like earthquakes and hurricanes, the resilience of materials directly impacts public safety and economic stability.

This collection will encompass a diverse array of topics essential to advancing our understanding and capabilities in structural engineering. Key themes include but are not limited to:

(1) Experimental studies on the behavior of structural materials subjected to blast and impact forces, aiming to uncover fundamental mechanisms and develop protective measures;

(2) Analytical modeling approaches to simulate and predict the response of structures under extreme loading conditions, facilitating the design of resilient systems;

(3) Numerical simulations that leverage advanced computational methods to model complex interactions between materials and dynamic forces;

(4) Application of machine learning techniques to analyze vast datasets and extract actionable insights for enhancing structural resilience.

At its core, this topic collection aligns with Discover Materials' mission to catalyze innovation in materials research across diverse applications. By publishing pioneering research in structural engineering, the collection aims to not only expand our fundamental understanding of materials behavior but also to accelerate the development of materials with enhanced properties for a safer and more sustainable built environment.

Authors are invited to submit original research articles, reviews, and case studies that contribute to the understanding of structural materials under extreme loading conditions. Submissions should emphasize practical applications and theoretical advancements relevant to the fields of structural engineering and materials science.

This Collection will serve as a valuable resource for researchers, engineers, and policymakers involved in the design, analysis, and implementation of materials in structural applications. It aims to foster collaboration and innovation in addressing the challenges posed by extreme loading scenarios through cutting-edge research and technological advancements.

Feature Conferences: 1. 2025 International Conference on Materials, Mechanical, and Civil Engineering Technologies (MMCET 2025), to be held in Tokyo, Japan, from December 17th to 19th, 2025. 2. 2025 2nd International Symposium on Civil Engineering and Smart Structure Technology (CESST 2025), to be held in Zhengzhou, China, from December 5th to 7th, 2025. High-quality papers presented at the conference will be invited for consideration in this Collection, ensuring a rigorous peer-review process. We welcome innovative research that advances knowledge in this critical field.Keywords: Structural Engineering; Extreme Loading Conditions; Blast and Impact Forces; Concrete Testing; Resilient Infrastructure; Material Performance; Simulations; Finite Element Modeling

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Sep 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in