Behind the Paper: How Pacific Warming Put the Brakes on Arctic Sea Ice Loss

Published in Earth & Environment

Our team noticed something unexpected. While global warming continued its upward march, even surpassing the symbolic 1.5°C Paris Agreement threshold in 2024, the precipitous fall of September Arctic sea ice—the annual minimum—seemed to stall. The record low set in 2012 still stood, unbroken. The trend in sea ice loss from 2007 to 2024 was statistically insignificant, a dramatic slowdown from the steep decline of the preceding decades. Why? What force was applying the brakes to Arctic sea ice melt in the face of relentless global heating?

This question became the catalyst for our study, "Decelerated Arctic Sea ice loss triggered by accelerated North Pacific warming over the past decade." The journey to the answer took us on a path far from the Arctic, to the warming waters of the North Pacific Ocean, revealing a powerful natural counterpunch to human-caused climate change in the polar north.

The Puzzling Slowdown

The first step was to confirm the signal wasn't just noise. By analyzing sea ice concentration data, we identified that the slowdown wasn't uniform across the Arctic. While some areas, like the Greenland Sea, continued to lose ice, two key regions were bucking the trend: the central Arctic Ocean near the 180th meridian (we called this Region 1) and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago (Region 2). In these areas, sea ice was actually increasing at rates of 0.4% and 1.1% per year, respectively. These regional gains were effectively offsetting losses elsewhere, causing the overall decline to flatline.

This immediately pointed us away from local, internal Arctic variability and toward a larger-scale, remote driver. The suspect? The atmosphere.

Connecting the Dots: From Pacific to Pole

Our investigation zeroed in on a key atmospheric pattern: the Arctic Dipole (AD). In its positive phase, the AD features high pressure over the Canadian Arctic and low pressure over the Siberian Arctic, a setup that typically promotes sea ice loss. However, our analysis revealed that the summertime AD index was in a significant downward trend from 2007 to 2024. This negative phase of the AD was the direct cause of the regional ice growth, fostering surface wind patterns that pushed ice into Region 1 and brought colder air over both regions, reducing melt.

But what was driving this shift in the Arctic Dipole? This is where the story gets interesting. When we traced the atmospheric pathways backward, we found a robust "wavetrain"—a series of high- and low-pressure systems snaking across the hemisphere. This wavetrain, visualized through geopotential height anomalies and wave activity flux, had its origins not in the Arctic, but in the North Pacific.

The link was the sea surface temperature (SST). Over the same period, the North Pacific was warming rapidly. By regressing atmospheric conditions onto our key sea ice regions and the AD index, we found that specific patterns of warm and cool SST anomalies in the Pacific were exciting these Rossby wavetrains. Positive SST anomalies in the tropical eastern Pacific, for instance, enhanced convective activity, acting as a starting pistol for these planetary waves. The waves then propagated northeastward, into the Arctic, where they disrupted the prevailing pressure systems, promoting the negative AD phase that, in turn, fostered sea ice growth.

To cement this statistical relationship, we turned to numerical modeling. Using the Community Atmosphere Model (CAM5), we ran an experiment where we forced the model only with the observed North Pacific SST anomalies. Strikingly, the model successfully reproduced the same atmospheric wavetrain and the resulting negative height anomalies over the Arctic. This was a crucial piece of evidence: the North Pacific warming was not just correlated with the Arctic changes; it was a primary driver.

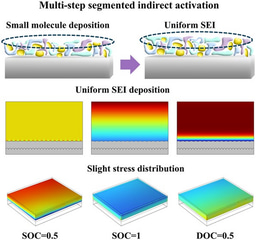

Dynamics vs. Thermodynamics: How the Ice Grew

Understanding why the ice grew led us to another layer of the puzzle: the interplay of dynamics and thermodynamics. Using a sophisticated coupled climate model (CESM1) with its winds "nudged" to match real-world observations, we could dissect the contributions.

The results were clear: the sea ice volume increase was predominantly shaped by dynamic processes. The anomalous wind patterns associated with the negative AD phase were physically pushing and piling up sea ice, particularly in Region 1. Think of it as a weather pattern that actively gathers and compacts the ice. Thermodynamic processes—primarily a reduction in top melt due to cooler air temperatures—also played a supporting role, but the dynamic component was the star of the show.

The Bigger Picture: A Temporary Respite in a Long-Term Decline

So, what is causing the North Pacific to warm so rapidly? Our analysis points the finger squarely at the usual suspect: greenhouse gases. An Empirical Orthogonal Function (EOF) analysis revealed that the primary mode of SST variability in the North Pacific is a broad-scale warming pattern consistent with anthropogenic forcing. The warming that is triggering the sea ice-preserving wavetrain is, ironically, largely a product of the same human activities that are driving the long-term Arctic melt.

This creates a fascinating and complex interplay. On one hand, anthropogenic forcing is directly accelerating Arctic sea ice loss. On the other, it is warming the North Pacific, which, through this newly identified teleconnection, is temporarily applying the brakes. The observed slowdown from 2007-2024 is the net result of these two competing influences.

This also helps explain why many current climate models (CMIP6) struggle to capture this slowdown. If their representation of these intricate Northern Hemisphere summer teleconnections is imperfect, they will miss this moderating feedback.

It is critical to view our findings not as a reversal of fortune for Arctic sea ice, but as a temporary deceleration. The long-term driver—greenhouse gas emissions—remains dominant. Projections of an ice-free Arctic summer before 2030 are still very much on the table. The North Pacific's intervention is likely a manifestation of natural variability superimposed on the human-caused trend, a nuance that highlights the complexity of our climate system.

Ultimately, this study illuminates a critical regulatory mechanism within the Earth's climate. It shows how changes in one part of the world can trigger a cascade of effects that modulate changes thousands of miles away. By untangling this connection between the Pacific and the Pole, we are not just explaining a recent pause in ice loss; we are adding a vital piece to the puzzle of climate prediction, helping to refine our models and improve our foresight into the future of our rapidly changing planet.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in