Beyond Project Cybersyn: The Hidden Story of Stafford Beer's Latin American Cybernetic Adventures

Published in Computational Sciences, Business & Management, and Law, Politics & International Studies

This hidden history doesn't just add footnotes to Beer's biography—it fundamentally changes how we understand both his work and the region's role in technological innovation. While Silicon Valley was still finding its feet, Latin American engineers and social scientists were pioneering applications of cybernetic principles that wouldn't look out of place in today's discussions of algorithmic governance and participatory democracy.

The article highlights the following:

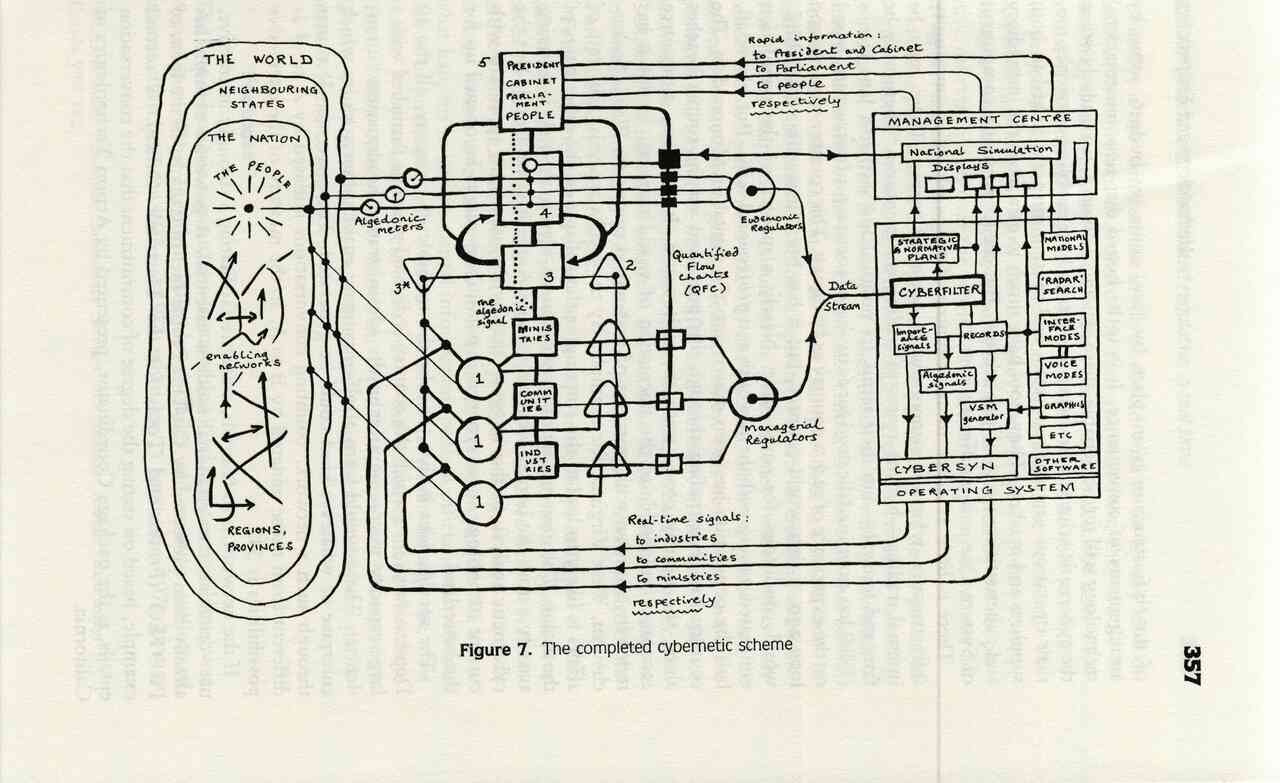

Beer's consulting firm SIGMA work for Chile's largest steel producer. What started as a straightforward industrial optimization project planted seeds that would grow into something much bigger.

Uruguay's URUCIB (1986-88): A sophisticated real-time information system for the presidency that actually worked, was later exported to Argentina and Nicaragua, and represented one of the first major software exports from Latin America.

Colombia's VSM experiments (1990s-2000s): Led by cybernetician Angela Espinosa, these projects applied Beer's Viable System Model to everything from auditing practices to educational reform, showing how cybernetic principles could enhance rather than replace democratic participation.

Mexico's corruption crisis: Beer spent over a year trying to optimize food distribution systems, only to watch funds disappear into the pockets of "aviator" bureaucrats. His memo to President Miguel de la Madrid reads like a cybernetic autopsy of institutional failure.

Venezuela's Cybervenez: What started as an ambitious alliance-building project collapsed amid economic crisis and the violent Caracazo protests of 1989.

Stafford Beer once wrote about "metamanagement"—the challenge of creating organizations that embrace existing organizations in larger wholes. His Latin American adventures were exactly that: an attempt to help entire nations become more adaptive, more democratic, more capable of learning and evolving.

Some experiments succeeded, others failed spectacularly. But together, they reveal a vision of technology that's neither utopian nor dystopian—just persistently, fascinatingly human. In an age when we're grappling with questions about AI governance, democratic participation, and technological sovereignty, these forgotten experiments offer both warnings and inspiration.

Follow the Topic

-

Systemic Practice and Action Research

This is a journal dedicated to critical systems thinking and its applications, with an emphasis on understanding modern societal complexities.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Systems Thinking to Advance the Sustainable Development Goals

This special issue of Systemic Practice and Action Research invites contributions that that explore the role of Systems Thinking in shaping, informing, and enabling the pursuit of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Ten years on from United Nations Member States’ adoption of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, only 18% of SDG targets are on track to be achieved. Gains have been made in areas such as education, clean energy adoption, and infrastructure expansion, but the overall trajectory is deeply concerning. Greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, species extinction is accelerating, and freshwater ecosystems are in decline. At the same time, billions of people still go hungry and lack access to safe drinking water.

The challenges encompassed by the SDGs represent some of the most complex issues of our time. They require collaboration, integrated decision making, and navigating the interdependencies between people, planet, and prosperity. Systems Thinking offers a range of methods and tools for engaging with the complexity of sustainability and regeneration. They can help us explore system behaviours, uncover different worldviews, and integrate marginalised voices.

This special issue seeks rigorous contributions of conceptual or real-world interventions that apply Systems Thinking to advance the SDGs.

We welcome contributions to one or more of the following objectives:

1. Showcase innovative applications of Systems Thinking to address complex sustainability challenges across geographical, cultural, and institutional contexts, for example, using system dynamics, causal loop diagrams, soft systems methodology, or critical systems heuristics etc.

2. Illustrate how Systems Thinking can enhance shared understanding, inform policy or enable collective action for sustainable development.

3. Reflect on the methodological strengths and limitations of Systems Thinking in sustainable development problem contexts.

4. Identify gaps and future research directions for advancing the use of Systems Thinking in pursuit of SDGs.

Prospective authors are invited to contact the guest editors with an extended abstract of a proposed paper via e-mail (m.hutcheson@ucl.ac.uk) prior to submitting the full manuscript. Full papers must be submitted through the journal online submission system (https://link.springer.com/journal/11213/submission-guidelines).

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Apr 03, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in