Black boxing "the environment": the last bastion of faith-based evolution education?

Published in Neuroscience

By Dustin Eirdosh & Susan Hanisch

In 2006, evolutionary biologist Ross Nehm wrote a powerful commentary in Bioscience, cheekily titled "Faith-Based Evolution Education". Nehm's point was not about religious faith, but rather, his concern that the growing evolution education advocacy and research community was developing without appropriate scientific rigor. The claims about how to teach evolution, according to Nehm, were based more on faith or belief than evidence. Nehm's point was well taken, and today he stands as one of the editors for the leading specialty journal for our field, Evolution Education & Outreach. So, 15 years after Nehm's article, is our field still "faith-based"? The answer, in nearly all respects, is no - the field has grown and matured in remarkable ways. Integration with the learning sciences has strengthened. New research instruments for measuring and assessing evolution understanding have been developed, validated, and put to work. An impressive diversity of national and international networks such as The National Center for Science Education (NCSE), the Teachers Institute for Evolution Science (TIES), EvoKE, and more, have rightly flourished by supporting educators with this emerging knowledge base. So, no, the evolution education research and advocacy community can no longer be painted broadly as faith-based.

Despite that remarkable scientific growth, we are concerned that there remains at least one last bastion in this landscape where faith-based, yet purportedly scientific claims still dominate. Unfortunately for our field, this arena, in which assumptions seemingly trump evidence, represents a central foundation for how we often guide educators and curriculum designers at the most fundamental level. The question at hand:

How should educators help students learn about the role of "the environment" in evolutionary processes?

This may seem like a rather small, technical, perhaps 'geeky' question, and for some in the evolution education world, it may seem a total non-issue. The environment is the source of selection that drives evolutionary change by creating the conditions that favor some variants over others. Simple. Done. Right? Not quite.

The evolutionary biologist's concept of the "the environment" is actually a science communication heuristic, a simple rule of thumb to make explanations easier to digest. In everyday language, the concept of "the environment" invokes images of the natural world, perhaps of forests, fields, deserts, the arctic, it is the ecosystems we know and love. Yet for the evolutionary biologist, the environment is something much more specific and encompassing, it includes the specifics of all relevant biotic and abiotic aspects of the context in which we find a trait or organism we are seeking to explain in evolutionary terms.

Despite this scientific view on the concept of "the environment", evolution education tends to (at least implicitly) advise educators to keep this concept vague. Take for example this comparison of artificial vs. natural selection in the highly influential Understanding Evolution resource from UC Berkeley:

Long before Darwin and Wallace, farmers and breeders were using the idea of selection to cause major changes in the features of their plants and animals over the course of decades. Farmers and breeders allowed only the plants and animals with desirable characteristics to reproduce, causing the evolution of farm stock. This process is called artificial selection because people (instead of nature) select which organisms get to reproduce.

On a surface level, there is absolutely nothing wrong with this statement, indeed there are substantial differences (as well as similarities) between artificial and natural selection. Our concern arises when the implicit assumption here (that "nature" does not include the variously goal-directed behaviors of individuals and others in the ecosystem) becomes enshrined as the baseline conception of what "the environment" means in evolution science. If students are not given many opportunities to clarify this concept, such problematic interpretations are likely to develop. Indeed, we continue to find that it is a mainstream conception among some evolution education specialists that organismal behaviors should be excluded from how students are instructed about the role of the environment in natural selection. Such arguments usually take the form of suggesting these cases are wholly separate concepts from natural selection, yet, as we have argued previously, such a view represents a failure of analogical reasoning, that is, a failure to think critically about both similarities and differences among concepts.

An example in which students can be engaged in unpacking the concept of the environment in evolution is the case of the Lactase Persistence (LP) gene, which has evolved in only some lineages of humans, allowing those with it to consume the dairy products of other species long after weaning. In this case, "the environment" includes not just the pastoral landscapes of the past, but also the actual behavior of those ancient ancestors who boldly experimented in milking their local ruminants prior to the emergence of this simple genetic mutation. "The environment" here includes all of the social, economic, and cultural dimensions that evolved around the dairying practices that would follow. We can even go so far as to say that, while difficult if not impossible to measure, conceptually and theoretically, the environment for the evolution of the LP gene also includes the subtle variations in preferences, emotions, and thoughts that motivated the actions of those early milk drinkers and dairy farmers.

So, evolutionary biologists, either implicitly or explicitly, think about the environment as including all of the behavioral dynamics relevant to the evolutionary context of the trait or organism we are interested in. Yet, if you are an educator seeking advice from (some) within the evolution education community, you will likely be told that students should only be exposed to this fact in "advanced graduate student seminars". You will be told (again, by some), that the concept of "the environment" must, in essence, remain an inscrutable black box for the purposes of K-12 general education. To be clear, not everyone agrees, for example, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Biointeractive resources on the Gene-Culture Co-Evolution of Lactase Persistence, is a great example engaging this view within high school curricula. More recently, the TIES network hosted evolutionary anthropologist Professor Brian Hare to engage biology teachers and students in understanding the self-domestication hypothesis in humans and bonobos. Though, importantly, in both cases these resources do not appear to provide explicit reflection on how the 'special case' of culture-led gene-culture coevolution relates to unpacking the more generalized concept of "the environment".

Despite such examples, for a significant and certainly dominant faction within the evolution education world, it would seem as if it is borderline heresy to suggest we should help students unpack the concept of the environment beyond vague generalizations. When one of us (Dustin) recently suggested in a leading evolution education forum that it is potentially problematic to universally abstract away the behavioral dynamics within the environment that so often influence evolutionary selection pressures, he was criticized by one member of the group as being "like a science denialist" and "worse than a creationist". Yikes! So, what exactly is the evidential basis for the claim that K-12 educators should never unpack the black box of the environment?

It turns out, there is none, no evidence whatsoever that this strategy of not clarifying the concept of "the environment" is helping students engage in scientifically adequate evolutionary reasoning across the tree of life. The conventional wisdom that, as a rule of thumb, educators must keep the details of the "environment" concept hidden from view, excluding the behavioral, cognitive, and cultural dynamics, is a matter of faith not science. Importantly, the belief is not entirely fact-free, yet how this view became the status quo in our field is itself an interesting case of the cultural evolution of evolution education science.

What has occurred is fairly simple. There is solid evidence that students of all ages struggle to understand the random processes (such as the role of genetic mutations) that are central to understanding evolution. As well, there is solid evidence that students of all ages struggle to appropriately integrate the role of goal-directed processes (such as the behaviors of individuals and others in the environment) within evolutionary explanations, sometimes relying instead on naïve Lamarckian or intelligent design beliefs (Shtulman 2017). If we think of these two facts as like bricks, then some within the evolution education community have then used these bricks, in various configurations, to build a wall against the deeply misguided creationist conception of an "intelligent designer". The argument becomes: based on student cognitive biases, and to prevent creationist misconceptions, there must be a strongly enforced proscription against including the role of goal-directed behaviors as elements of evolutionary explanations, and so we must insist that educators not allow students to think of the concept of "the environment" as including organisms with behaviors, needs, or preferences. The basic facts on which this wall has been built are solid, but the wall was built in the wrong place - keeping out not only creationists, but an entire landscape of fascinating and rigorous evolutionary science.

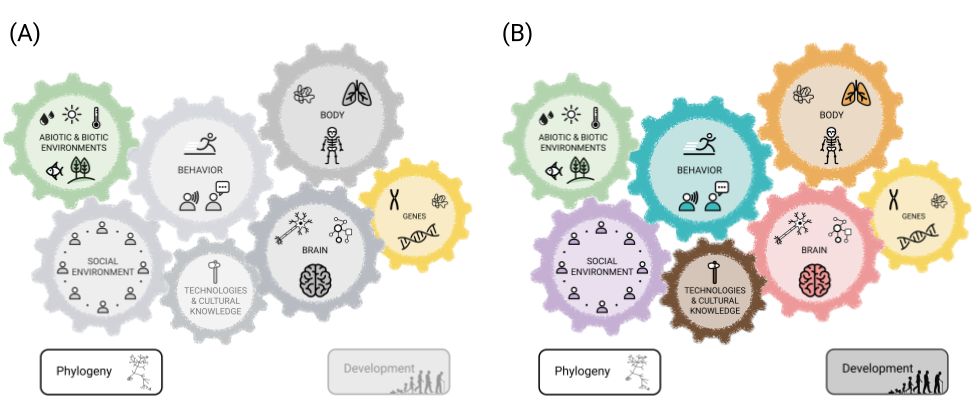

Critically, evolution education in the K-12 general education space does explicitly have the aim of empowering students to understand human origins. This is a space in which it is absolutely essential to unpack the environment concept into its constituent parts (Fig.1B). Even beyond humans however, understanding the evolutionary history of species as diverse as domesticated agricultural species, dogs, primates, earthworms, snails, killer whales, bacteria, beavers, and so many more (see NicheConstruction.com for additional examples and references) - all require some formulation of understanding behavioral dynamics as part of the environment - an understanding of behavior as selection pressure as a generalized principle spanning many (not all) examples of evolutionary change across the tree of life (see Hanisch & Eirdosh 2020a).

Critics of our claim will say there is no evidence that our suggestion wouldn't confuse young minds, that it is too complex, and must wait until graduate school (which most students will not ever reach!). On the contrary, concepts like domestication are routinely used as primary school introductions to evolutionary processes, cross-species co-evolution is sometimes taught in middle and early secondary levels, and in Germany, cultural evolution is a standard part of high school biology (see Hanisch & Eirdosh 2020b). It is simply that (some) evolution education experts suggest that these be taught as special cases, unrelated to the generalized concept of "the environment" (again, see our clarification on learning transfer and analogical reasoning in evolution education).

Also contrary to the view of our critics, given the lack of current evidence on effective learning trajectories in evolution understanding, there is an onus on them to demonstrate that keeping the environment concept locked within a black box until graduate school is more helpful than it is harmful. The persistence of learning difficulties in evolutionary understanding within this environmental-black box model of evolution education does not help their case. The persistence of misconceptions among some leading evolution education advocates regarding this issue even further speaks to the problematic nature of the current state of affairs.

We end with a call for unity among the evolution education research community. Our claims do provide stark challenges to long and deeply help assumptions within our field, and so we expect and welcome respectful pushback. Critically, let us not divide ourselves in unhelpful ways over this nuanced yet important point. Instead, we have laid our cards on the table. The evidential basis and purported educational potentials for these competing educational policy proposals is now clear - so let us work together to gather the evidence and finally place this last bastion of faith-based evolution education on a solid scientific foundation.

References

Hanisch, S. & Eirdosh, D. (2020a). Educational potential of teaching evolution as an interdisciplinary science. Evolution: Education and Outreach, 13 (25). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-020-00138-4

Hanisch, S. & Eirdosh, D. (2020b). Causal Mapping as a Teaching Tool for Reflecting on Causation in Human Evolution. Science & Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-020-00157-z

Nehm, R. H. (2006). Faith-based evolution education?. BioScience, 56(8), 638-639.

Shtulman, A. (2017). Scienceblind: Why our intuitive theories about the world are so often wrong. Hachette UK.

Follow the Topic

Your space to connect: The Psychedelics Hub

A new Communities’ space to connect, collaborate, and explore research on Psychotherapy, Clinical Psychology, and Neuroscience!

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in