Clinical Testing of the cAd3-Ebola and MVA-EbolaZ vaccines

Published in Microbiology, Biomedical Research, and Immunology

In March of 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that cases of Ebola virus disease (EVD) were spreading in Guinea. The outbreak raged through Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, reaching epidemic proportions. All EVD outbreaks to-date have been caused by one of three viruses of the Ebolavirus genus: Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV), Sudan ebolavirus (SUDV), or Bundibugyo ebolavirus (BDBV) (Yamaoka & Ebihara, 2021). The etiologic agent of the 2014-2016 epidemic was EBOV, historically the deadliest of the three. By the time the epidemic was declared over, EVD would claim over 11,000 lives, a 39% mortality rate among over 28,000 cases (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). This was at least 40 times larger than any previous outbreak of EVD. With a small number of exported cases also identified in Italy, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, Spain, the United Kingdom (UK), and the United States (US), the epidemic appeared poised to become a pandemic. In August of 2014, the WHO declared the epidemic a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), triggering an acceleration in the development of EVD vaccines.

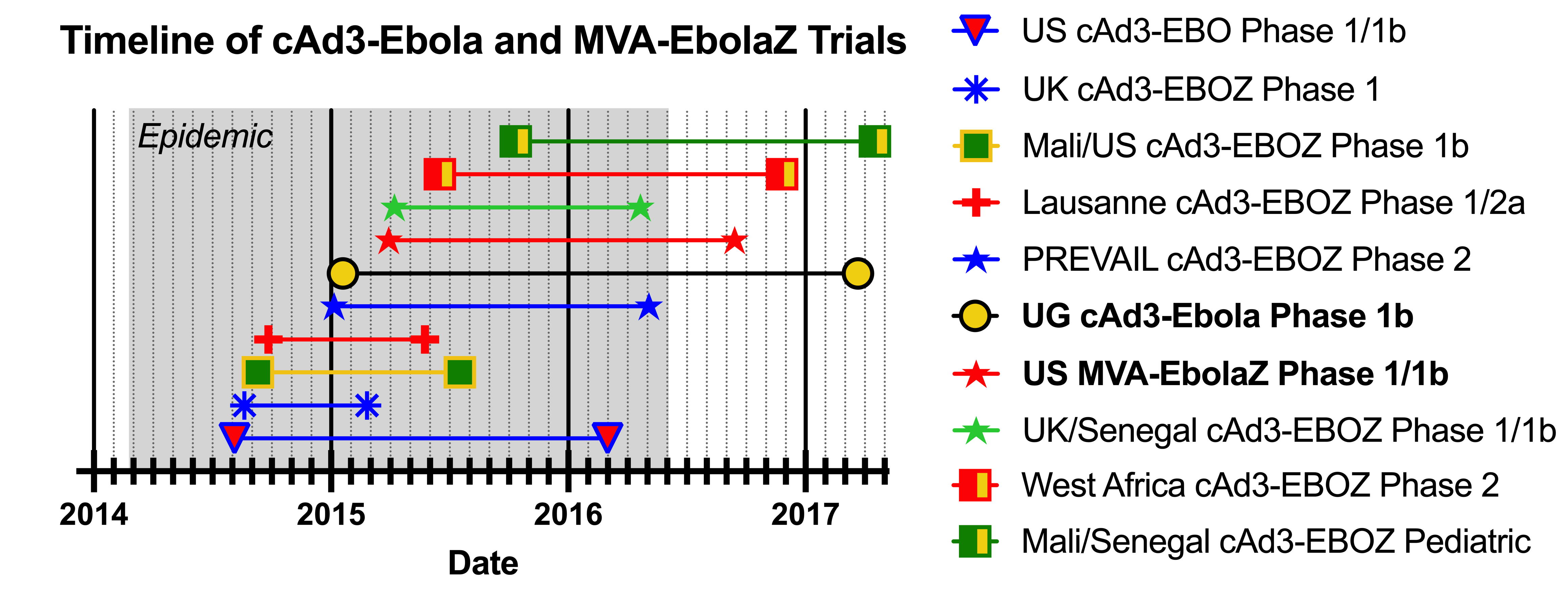

At the time, clinical development of replication-deficient chimpanzee adenovirus serotype 3 (cAd3)-vectored EVD vaccines was ongoing at the Vaccine Research Center (VRC) of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. The cAd3-vectored vaccines developed at the VRC express the surface glycoproteins (GPs) of either EBOV (cAd3-EBOZ, a monovalent vaccine), SUDV (cAd3-EBO S, a monovalent vaccine), or both EBOV and SUDV (cAd3-EBO, a bivalent vaccine). The term cAd3-Ebola is used herein when referring to the cAd3-EBO and cAd3-EBOZ vaccines collectively. Preclinically, the cAd3-Ebola vaccines demonstrated promising results, including protective efficacy in a cynomolgus macaque lethal EBOV challenge model (Stanley et al., 2014), warranting their further evaluation in clinical trials (Figure 1).

A phase 1 clinical trial assessing the cAd3-Ebola vaccines, originally scheduled to begin in the US in 2015, was expedited in light of the emerging outbreak. In September of 2014, the VRC, in collaboration with a team at Oxford University, UK (Ewer et al., 2016), initiated clinical trials evaluating the cAd3-EBO and cAd3-EBOZ vaccines. Preliminary results demonstrated these vaccines were safe and immunogenic (Ledgerwood et al., 2015). Subsequent phase 1 clinical trials of cAd3-EBOZ also began in Mali and Switzerland before the end of 2014 (De Santis et al., 2016; Tapia et al., 2016). The Liberian Ministry of Health requested investigational interventions from the US in October of 2014, leading to a placebo-controlled phase 2/3 Partnership for Research on Ebola Vaccines in Liberia (PREVAIL) clinical trial starting in February of 2015 (Kennedy et al., 2017). In the phase 2 component of the trial, the cAd3-EBOZ vaccine was evaluated in 500 adults. It was found to be safe, and a single dose increased Ebola-specific antibody levels by one month after vaccination which remained elevated for up to a year. While the PREVAIL trial was designed to include a phase 3 prevention component, the incidence of EVD declined in Liberia before efficacy could be evaluated, and the epidemic was declared over in June of 2016.

Coincident with the start of the PREVAIL trial (Figure 1), a phase 1b clinical trial of the cAd3-Ebola vaccines began in Uganda (UG). In the UG phase 1b clinical trial, both cAd3-EBO and cAd3-EBOZ were assessed. As described in our current report, along with 69 naïve participants, the UG trial recruited 21 participants with prior DNA Ebola vaccine exposure. Compared to naïve recipients, antibody titers peaked earlier after cAd3-EBO administration and were sustained at a higher titer in those with prior Ebola vaccine exposure. These results demonstrated that the DNA Ebola vaccines (Kibuuka et al., 2015; Sarwar et al., 2015) prime the immune system for a rapid recall to cAd3-EBO, and that cAd3-EBO is safe in both naïve and antigen-exposed individuals.

In preclinical models, the duration of protective immunity elicited by the cAd3-Ebola vaccines was enhanced by boosting with a modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) vector encoding EBOZ GP (Stanley et al., 2014). These results were reinforced by data from the UK and Mali trials, in which the cAd3-EBOZ vaccine response was effectively boosted by a licensed MVA-vectored vaccine. The VRC conducted a phase 1/1b first-in-human clinical trial in the US to assess an unlicensed MVA-vectored EBOZ GP-expressing vaccine (MVA-EbolaZ). As also described in our recent report, MVA-EbolaZ proved safe and immunogenic alone and as a boost to the cAd3-Ebola vaccines. The US clinical trial assessed prime-boost interval lengths of 6 to up to 52 weeks to determine the immunological impact of a range of prime-boost intervals. Longer intervals benefitted maintenance of antibody titers, while shorter intervals modestly improved the T cell response. Once MVA-EbolaZ proved safe and immunogenic in US participants, this boost was offered to UG participants who had previously received cAd3-Ebola. The cAd3-Ebola and MVA-EbolaZ vaccine regimen was safe and well tolerated in healthy adults in UG, eliciting immune responses durable for at least 48 weeks after each vaccine. Importantly, MVA-EbolaZ boosted EBOZ GP-specific titers to a uniformly high peak in just two weeks in both trials.

The cAd3-Ebola vaccines have now been evaluated in over 4,800 participants across both phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials (Figure 1) (Mwesigwa et al., 2023). MVA-EbolaZ and all of the cAd3-vectored EVD vaccines have an excellent safety record. Additionally, the VRC-developed monovalent SUDV vaccine, cAd3-EBO S, has demonstrated safety and immunogenicity in early phase clinical testing (Mwesigwa et al., 2023). A unique aspect of the cAd3-Ebola and MVA-EbolaZ vaccine regimen is that each dose elicits robust antibody titers lasting for at least 48 weeks. This regimen is expected to provide rapid protection after cAd3-Ebola that can then be boosted with MVA-EbolaZ any time from 6 weeks to a year after cAd3-Ebola. Along with cAd3-EBO’s multivalency, the safety and flexible timing of the MVA-EbolaZ boost make this a promising regimen suitable for use in both prophylactic and outbreak settings. Addition of the cAd3-EBO, MVA-EbolaZ vaccine regimen to the EVD vaccine portfolio would add flexibility and choice to the global arsenal of EVD vaccines.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, March 8, 2019). 2014-2016 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa. Retrieved 2021/08/24 from https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/history/2014-2016-outbreak/index.html

De Santis, O., Audran, R., Pothin, E., Warpelin-Decrausaz, L., Vallotton, L., Wuerzner, G., Cochet, C., Estoppey, D., Steiner-Monard, V., Lonchampt, S., Thierry, A. C., Mayor, C., Bailer, R. T., Mbaya, O. T., Zhou, Y., Ploquin, A., Sullivan, N. J., Graham, B. S., Roman, F., . . . Genton, B. (2016). Safety and immunogenicity of a chimpanzee adenovirus-vectored Ebola vaccine in healthy adults: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding, phase 1/2a study. Lancet Infect Dis, 16(3), 311-320. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00486-7

Ewer, K., Rampling, T., Venkatraman, N., Bowyer, G., Wright, D., Lambe, T., Imoukhuede, E. B., Payne, R., Fehling, S. K., Strecker, T., Biedenkopf, N., Krahling, V., Tully, C. M., Edwards, N. J., Bentley, E. M., Samuel, D., Labbe, G., Jin, J., Gibani, M., . . . Hill, A. V. (2016). A Monovalent Chimpanzee Adenovirus Ebola Vaccine Boosted with MVA. N Engl J Med, 374(17), 1635-1646. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1411627

Kennedy, S. B., Bolay, F., Kieh, M., Grandits, G., Badio, M., Ballou, R., Eckes, R., Feinberg, M., Follmann, D., Grund, B., Gupta, S., Hensley, L., Higgs, E., Janosko, K., Johnson, M., Kateh, F., Logue, J., Marchand, J., Monath, T., . . . Group, P. I. S. (2017). Phase 2 Placebo-Controlled Trial of Two Vaccines to Prevent Ebola in Liberia. N Engl J Med, 377(15), 1438-1447. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1614067

Kibuuka, H., Berkowitz, N. M., Millard, M., Enama, M. E., Tindikahwa, A., Sekiziyivu, A. B., Costner, P., Sitar, S., Glover, D., Hu, Z., Joshi, G., Stanley, D., Kunchai, M., Eller, L. A., Bailer, R. T., Koup, R. A., Nabel, G. J., Mascola, J. R., Sullivan, N. J., . . . Ledgerwood, J. E. (2015). Safety and immunogenicity of Ebola virus and Marburg virus glycoprotein DNA vaccines assessed separately and concomitantly in healthy Ugandan adults: a phase 1b, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. The Lancet, 385(9977), 1545-1554. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62385-0

Ledgerwood, J. E., Sullivan, N. J., & Graham, B. S. (2015). Chimpanzee Adenovirus Vector Ebola Vaccine--Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med, 373(8), 776. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1505499

Mwesigwa, B., Houser, K. V., Hofstetter, A. R., Ortega-Villa, A. M., Naluyima, P., Kiweewa, F., Nakabuye, I., Yamshchikov, G. V., Andrews, C., O'Callahan, M., Strom, L., Schech, S., Anne Eller, L., Sondergaard, E. L., Scott, P. T., Amare, M. F., Modjarrad, K., Wamala, A., Tindikahwa, A., . . . Stein, J. A. (2023). Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of the Ebola Sudan chimpanzee adenovirus vector vaccine (cAd3-EBO S) in healthy Ugandan adults: a phase 1, open-label, dose-escalation clinical trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 23(12), 1408-1417. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00344-4

Sarwar, U. N., Costner, P., Enama, M. E., Berkowitz, N., Hu, Z., Hendel, C. S., Sitar, S., Plummer, S., Mulangu, S., Bailer, R. T., Koup, R. A., Mascola, J. R., Nabel, G. J., Sullivan, N. J., Graham, B. S., Ledgerwood, J. E., & Team, V. R. C. S. (2015). Safety and immunogenicity of DNA vaccines encoding Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus wild-type glycoproteins in a phase I clinical trial. J Infect Dis, 211(4), 549-557. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiu511

Stanley, D. A., Honko, A. N., Asiedu, C., Trefry, J. C., Lau-Kilby, A. W., Johnson, J. C., Hensley, L., Ammendola, V., Abbate, A., Grazioli, F., Foulds, K. E., Cheng, C., Wang, L., Donaldson, M. M., Colloca, S., Folgori, A., Roederer, M., Nabel, G. J., Mascola, J., . . . Sullivan, N. J. (2014). Chimpanzee adenovirus vaccine generates acute and durable protective immunity against ebolavirus challenge. Nat Med, 20(10), 1126-1129. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3702

Tapia, M. D., Sow, S. O., Lyke, K. E., Haidara, F. C., Diallo, F., Doumbia, M., Traore, A., Coulibaly, F., Kodio, M., Onwuchekwa, U., Sztein, M. B., Wahid, R., Campbell, J. D., Kieny, M.-P., Moorthy, V., Imoukhuede, E. B., Rampling, T., Roman, F., De Ryck, I., . . . Levine, M. M. (2016). Use of ChAd3-EBO-Z Ebola virus vaccine in Malian and US adults, and boosting of Malian adults with MVA-BN-Filo: a phase 1, single-blind, randomised trial, a phase 1b, open-label and double-blind, dose-escalation trial, and a nested, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 16(1), 31-42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00362-X

Yamaoka, S., & Ebihara, H. (2021). Pathogenicity and Virulence of Ebolaviruses with Species- and Variant-specificity. Virulence, 12(1), 885-901. https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2021.1898169

Follow the Topic

-

npj Vaccines

A multidisciplinary journal that is dedicated to publishing the finest and high-quality research and development on human and veterinary vaccines.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Therapeutic HPV vaccines

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 30, 2026

Lipid nanoparticle (LNP)-adjuvanted vaccines

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: May 19, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in