Computational mining the anticancer potential of non-oncology drugs

Published in Cancer, Protocols & Methods, and Biomedical Research

The field of cancer genomics has made remarkable advances over the past two decades, as researchers have identified a vast number of cancer-causing mutations and facilitated the development of targeted therapies. Unfortunately, despite billions of dollars invested in research and development, coupled with the lengthy development cycles of traditional drug discovery, only a small fraction of this genetic knowledge has been translated into effective anticancer drugs. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop methods that can accelerate the translation of cancer genomics insights into specific therapeutic regimens, enabling more patients to benefit from these scientific breakthroughs.

One promising strategy is drug repurposing, which involves using clinically available drugs for diseases outside their original therapeutic scope. The advantage of this approach is that it significantly reduces the time required for drug development. Not only are these drugs readily accessible, but their safety profiles have already been rigorously evaluated prior to their initial approval. This is the foundation of our work: leveraging drug repurposing to address the current shortage of anticancer therapies by tapping into an "arsenal" of non-oncology drugs that are already within reach. Our plan was to use machine learning algorithms to analyze successful cases of non-oncology drugs being repurposed for cancer treatment. By building a predictive model, we aimed to match these drugs with patients based on their genetic profiles.

However, we quickly encountered a major challenge: the number of known success cases was limited, and even more troubling, very few of these cases included detailed genetic information about the patients who benefited. This made it nearly impossible to establish a clear link between a specific drug and a specific patient. Many published studies on drug repurposing relied on non-individualized data, assuming that patients with the same disease share similar causative factors. While this assumption might hold for diseases like COVID-19, it is far less applicable to cancer. Cancers are genetically heterogeneous, meaning the mutations driving the disease can vary significantly from patient to patient. Just as we were grappling with this issue, we came across a groundbreaking study by researchers from Harvard and MIT. They conducted a large-scale drug screening experiment to evaluate the inhibitory effects of non-oncology drugs on the proliferation of cancer cells. Crucially, the genetic information of the cancer cell lines used in their experiments was well-documented. This provided us with the data we needed to establish connections between non-oncology drugs and the genetic profiles of tumor cells.

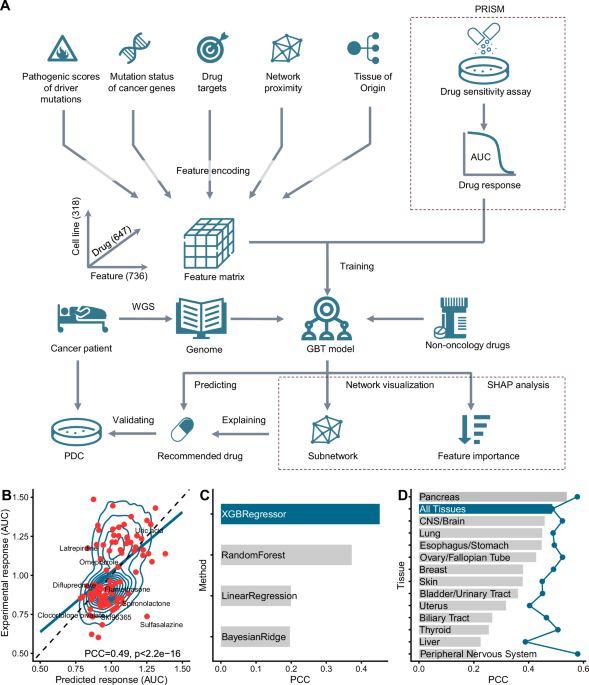

To utilize data on genetic variations in tumor cells and their responses to drugs, we needed to encode information about genetic mutations and drug targets into feature vectors that could be processed by computers. Machine learning algorithms were then employed to build a statistical model capable of distinguishing between effective and ineffective drugs by comparing their corresponding feature vectors. This process, known as feature engineering, is critical because well-designed features should capture the core aspects of the problem. Since our goal was to use existing drugs to treat abnormal cellular processes driven by genetic mutations, we hypothesized that these drugs would be effective if their targets overlapped with the biological pathways affected by the mutations. To encode this relationship, we utilized protein-protein interaction networks to establish a meaningful representation between a drug’s target and the genetic variations in each cell. By incorporating additional information, such as the pathogenicity scores of genetic variants and the importance of each drug target, we developed a model capable of accurately predicting how tumor cells with specific mutations would respond to particular non-oncology drugs. We named this model CHANCE, reflecting our hope that it will create new therapeutic opportunities for cancer patients and unlock the potential of known drugs for novel applications.

After analyzing the genomic data of approximately 5,000 tumors spanning multiple cancer types using CHANCE, we found that nearly 30% of patients might benefit from specific non-oncology drugs. This is an encouraging statistic. In our experimental validation of CHANCE’s predictions, we also made some surprising discoveries. For example, pimavanserin, a drug used to treat hallucinations and delusions in Parkinson’s disease patients, demonstrated potent activity against tumor cells in a pancreatic cancer patient. Similarly, tumor cells from an esophageal cancer patient showed remarkable sensitivity to eltrombopag, a drug typically used to treat thrombocytopenia. These findings highlight the potential of our individualized drug repurposing model to uncover hidden therapeutic opportunities within non-oncology drugs. We hope that CHANCE will serve as a valuable tool for experimental and clinical researchers, enabling them to explore the untapped potential of existing drugs and ultimately improve outcomes for cancer patients.

Follow the Topic

-

npj Precision Oncology

An international, peer-reviewed journal committed to publishing cutting-edge scientific research in all aspects of precision oncology from basic science to translational applications to clinical medicine.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

AI Approaches in Drug Design

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Genomic Instability

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in